Chelation therapy reduces lead-exposure problems but could create lasting effects for children treated for autism, CU researchers find

By Krishna Ramanujan

Lead chelation therapy -- a chemical treatment to remove lead from the body -- can significantly reduce learning and behavioral problems that result from lead exposure, a Cornell study of young rats finds.

However, in a further finding that has implications for the treatment of autistic children, the researchers say that when rats with no lead in their systems were treated with the lead-removing chemical, they showed declines in their learning and behavior that were similar to the rats that were exposed to lead.

Chelating drugs, which bind to lead and other metals in the blood, are increasingly being used for the treatment of autism in children.

"Although these drugs are widely used to treat lead-exposed children, there is remarkably little research on whether or not they improve cognitive outcomes, the major area of concern in relation to childhood lead poisoning," said Barbara Strupp, Cornell associate professor of nutritional sciences and of psychology and the senior author of the study, which was published in a recent issue of Environmental Health Perspectives.

Studies on the safety or effectiveness of the drugs for treating autism are similarly lacking, Strupp said.

Strupp added that to her knowledge this is the first report that shows that chelation therapy can reduce behavioral and learning problems due to lead exposure as well as the first to show that this type of treatment can have lasting adverse effects when administered in the absence of elevated levels of heavy metals.

The study used succimer (brand name, Chemet), the most widely prescribed drug for the treatment of lead poisoning. Doctors prefer succimer to other such drugs because it can be given orally on an outpatient basis, and it leaches less zinc, iron and other essential minerals out of the body. Although the Centers for Disease Control recommends chelation therapy only for children whose blood lead levels exceed 45 micrograms per deciliter, such drugs as succimer are commonly administered at much lower levels of exposure, due to concerns about lasting complications with even slightly elevated blood lead levels.

It is important to remove lead from the body as quickly as possible to prevent or lessen lasting damage to the developing brain. High-lead exposure from peeling lead-based paint can lead to coma, convulsions and even death. At lower levels, lead exposure causes attention deficits, delinquency and difficulty regulating emotions and can lower IQ scores at a rate of about one IQ point per microgram/deciliter of exposure.

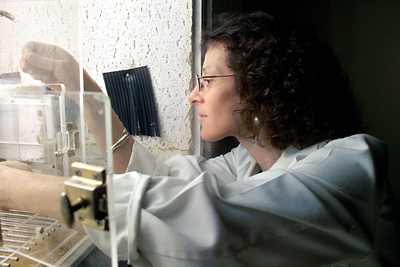

The study used rats -- whose mental and behavioral responses to lead exposure are similar to humans' -- and exposed them to moderate- and high-lead levels (administered via mothers' milk). A third group -- the control -- was not exposed. Exposures were followed by a treatment with succimer or placebo. Immediately thereafter, the researchers conducted automated tests over six months on the rats' attention, memory and abilities to learn and regulate emotions.

The rats with moderate-lead exposure benefited greatly from the succimer: Their test results were indistinguishable from the control test results. Rats exposed to higher lead levels showed benefits in the emotional domain: After succimer treatment, they behaved similarly to the control group. However, the treatment only slightly improved their learning deficit.

In the group that had no lead exposure but were given succimer, "we found lasting cognition and emotion-regulation [deficits] that were as pervasive and large as rats with high lead exposure," said Strupp. She added that one possibility is that succimer, in the absence of lead, may disrupt the balance of such essential minerals as zinc and iron. "These findings raise concerns about the use of chelating agents in treating autistic children," she said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Among other colleagues, Diane Stangle, a psychology graduate student, and Stephane Beaudin, a research associate in nutritional sciences, contributed to this work.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe