New to science, a novel insect eye could be a very old way of seeing

By Roger Segelken

An unusual type of eye -- resembling a tiny raspberry and possibly following a design principle that vanished with the extinction of trilobites hundreds of millions of years ago -- lives today in a parasitic insect, Cornell biologists report in the Nov. 5 issue of the journal Science.

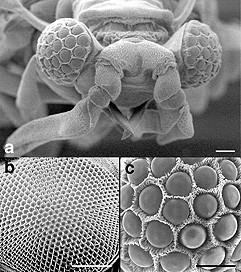

The compound eyes of most insects have many hundreds of lens facets, each sampling only one small point in the insect's visual field, but the composite lens eyes of strepsipteran insects have no more than 50 facets.

Fewer facets does not mean poorer vision, the Cornell biologists believe. The strepsipteran lenses are larger, and each has about 100 receptors, forming an individual retina behind each lens. According to the investigators, this kind of eye is well equipped to sample not points but "chunks" of the visual field, greatly improving the visual capabilities of these strange insects.

"No other insect that we know of has eyes quite like this," said Ron Hoy, professor of neurobiology and behavior at Cornell and co-author, with Cornell postdoctoral associates Elke Buschbeck and Birgit Ehmer, of the Science report. "The only place one may see a comparable eye structure is in the fossils of some kinds of trilobites," he says, referring to the extinct arthropods that lived in shallow seas during the Paleozoic era.

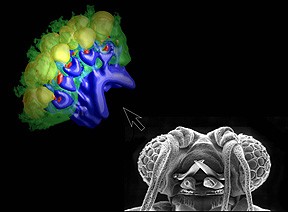

Strepsipteran insects, such as the Xenos peckii species studied by the Cornell biologists, don't dwell in water, but they do have short, secretive lives. The seldom-seen parasites are hidden in the bodies of common paper wasps (See fact sheet, "Looking at an Odd-ball Insect," attached). Female X. peckii never leave their wasp hosts, and when males do, they are on a specific, hurried mission: In the approximately two hours before they die, the males have to find another wasp that is parasitized by a female X. peckii, mate with the female and depart. "Sex pheromones from females probably help males to locate the general neighborhood of a wasp with a female parasite," Ehmer says, "but the male presumably relies on his vision once he is close to the wasp." She said that the importance to the insect of the visual system also is apparent from the volume of optic lobes dedicated to processing visual information, which Ehmer estimates to be 75 percent of the insect's brain.

Compared with a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with more than 700 facets in each compound eye, X. peckii has only about 50 facets per eye. Each of the X. peckii facets, referred to as "eyelets" by the biologists, is about 65 microns (65 millionths of a meter) in diameter and covers about the same area as 15 of the smaller fruit fly lenses. The fruit fly eye has only eight photoreceptors per facet, with each facet contributing to one sample point.

"The need for a tiny insect eye to gather lots of light and bring images into sharp focus on the receptors may explain the advantage of the eyes that deliver images in chunks instead of points," Buschbeck says. "This composite lens arrangement allows the insect to have many more photoreceptors in a given area than would be possible with a compound eye. If you only have so much space on your head for eyes and you want to gather the most light, you want a composite lens eye," she says.

"The larger lenses of the strepsipteran insects are similar to a large lens of a camera," Buschbeck explained. "Large insect lenses admit more light, support more photoreceptors and permit higher resolution. Another important condition for vision is that the image is focused on the retina (just as the camera lens image should be focused on the film) and we have confirmed this with measurements made through the insect's lens."

However, an insect viewing the world in fewer but larger chunks of the visual field would seem to have an inverted, mirror-image problem. Like any simple lens, each eyelet inverts or reverses its individual portion of the overall image. Without some means of correction, the parasitic insect trying to read the first three words of this sentence and seeing each word with one of its eyelets might instead read tuohtiW emos snaem.

The correction comes about, the Cornell biologists believe, because of chiasmata, which are X-shaped nerve crossings named for the Greek letter chi. The biologists found that behind each of the eyelets is a nerve that connects that eyelet to the brain. The nerve exhibits a chiasma, rotating the nerve 180° around its own axis and re-inverting each portion of the image.

"We're certainly not claiming that this insect descended from the trilobites or anything like that," Hoy commented. "What strepsipteran insects and trilobites have in common is that they are arthropods -- but so are lobsters and crabs and all the other insects -- and that the structures of their eyes appear analogous -- at least from what one can tell from the body surface of ancient fossils."

Research resulting in the Science article, "Chunk Versus Point Sampling: Visual imaging in a Small Insect," was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Looking at an Odd-ball Insect

Strepsipteran insects, such as the Xenos peckii examined by Cornell biologists for clues to its unusual visual system, are so different from other insects that they have been placed in their own insect order, strepsiptera, with about 500 known species. Although they exhibit some flylike characteristics, such as flight-stabilization structures located next to the wings, strepsipteran insects have antennae that more closely resemble those of beetles.

When it comes to strepsipteran oddness, the eyes have it. The most prominent part of the insect's head, the large, composite eyes, protrude to the side. Each convex lens facet, or eyelet, in the composite eye is separated from its neighbors by rows of fine, brushlike hairs called microtrichia. The microtrichia are believed to block stray light from reaching the eyelets, as do matte-surfaced hoods around camera lenses. Viewed through a microscope, the composite eyes resemble ripe raspberries.

Only the males fly (and only the males possess the eyes in question), and only for a couple of hours, as the to 3- to 4-millimeter long parasites emerge from the bodies of their hosts -- paper wasps -- to search for potential mates. Female strepsipteran insects don't take an active role in the courtship: Sightless, flightless sacs of developing eggs, the females wait inside wasp hosts for a male to find them. Females are thought to emit a sex pheromone to help attract males, but the males might rely on their eyesight once they are close to a wasp harboring a female.

For the wasps, being parasitized by strepsipteran insects usually is not fatal. Unlike some doomed insects, whose insides are consumed by parasites until they become a hollow shell, paper wasps with strepsipteran insects inside merely lose some interior space and a chance to reproduce. The parasites occupy room normally required for the wasp's reproductive organs, which may not become fully developed.

Strepsipteran insects would not be a useful biocontrol for paper wasps. The parasitism rate varies tremendously by region but rarely exceeds one in 100 wasps. And the parasites usually do not kill their hosts -- just limit their reproduction -- so reducing the population of paper wasps with strepsipteran insects could take forever. But it's just as well: Among all the stinging insects, the less aggressive paper wasps are not a major pest. Although their nests may be a nuisance to homeowners, paper wasps seldom sting unless provoked or threatened.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe