Cornell Rewind: White buys Europe's finest books, profs

Introducing “Cornell Rewind,” a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle for the next 15 months written by University Archivist Elaine Engst and the Chronicle’s Blaine Friedlander. As part of Cornell’s sesquicentennial celebration each month, this column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise the university’s rich tapestry of history.

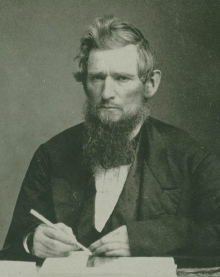

Months before the first students arrived for the first-ever semester at Cornell University, the school’s tiny faculty and administration – chiefly President Andrew Dickson White – set about placing figurative cornerstones for educational success.

In short, it was a shopping trip to Europe: In search of the finest books, quality chemicals, superior mechanical apparatus and learning tools, and – with any luck – blue-chip professors, the 36-year-old White set off by steamship in April 1868.

Prior to White’s trip, professor of agricultural chemistry George Caldwell – White’s first faculty hire – busily assembled shopping lists. “My list includes everything for a fair working laboratory and for illustration of lectures; there is but little in there beyond the ordinary working materials of this chemist,” Caldwell wrote to the White in November 1867. “I … hope that we shall have gas to burn in the laboratories – it makes a difference.”

Other newly hired professors sent Caldwell their lists – and Caldwell dutifully passed them along. “On Thursday last I received from Professor [James] Crafts with lists of apparatus which I forward to you … as seem to be necessary,” Caldwell told White. “Crafts has completed lists with illustrations from German catalogues. … You will see that I have made a considerable number of additions to his lists.”

For the entirety of White’s journey to stock the new university, he spent about $60,000 – over $1 million in today’s economy. White purchased the 1,478-volume personal library of noted University of Berlin philologist Franz Bopp, as the entire scholarly set was offered by Bopp’s widow. Proudly, White told the university trustees that he had “finally secured it at a price considerably below my anticipation.” He continued: “I may say that immediately after the conclusion of our arrangement, a larger sum was offered by another institution.” Cornell’s Rare and Manuscript Collections maintains the Bopp collection.

While his letters to Ezra Cornell detail with great excitement his purchases, he emphasized the scientific equipment that he knew would be of the most interest to Cornell. White also bought other items that clearly struck his own fancy. When he purchased a set of plaster “gems,” small classical models from the Royal Museum at Berlin, he assured Cornell that he had used his own money.

White also purchased a consequential collection of 187 plow models made by Ludwig von Rau of the Royal Agriculture College of Hohenheim, Germany. “From the crudest plough used in bible times and earlier to the English Howard plough and American-improved ploughs [of] all important makes and categories given,” White wrote in a letter to Ezra Cornell. “Some are exceedingly curious and form examples of implied ingenuity – but altogether they are very interesting and instructive.”

At the forefront of medicine, French anatomist Louis Auzoux had created highly accurate papier-mâché animal and human body anatomical models – for medical professionals and for students – that could be taken apart and examined. Certainly the new Cornell students would put it to use. In Paris, White purchased a set.

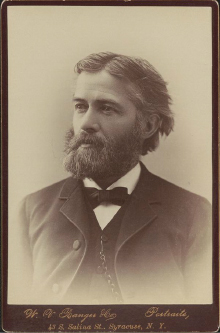

Arguably White’s greatest triumph in Europe was absconding with famed European professors James Law, a young veterinary professor from Edinburgh who had studied under Joseph Lister, the pioneer in antiseptic medicine, and Goldwin Smith, an already celebrated professor of history from Oxford University. In itself, attaining Law was a conquering achievement, but the news of acquiring Smith to open the university’s doors the following October was so exciting that White urged Cornell to tell the newspapers.

With an apparent 19th century sense of humor and eloquently understated, White wrote in his autobiography: “I had ‘brought back an Oxford professor and a Scotch horse-doctor.’ But never were the selections more fortunate.”

In an autobiographical memoir, White explained: “Professor Smith entered at once into our plans heartily … lectured for us year after year as brilliantly as he had ever lectured at Oxford … gave his library to the university, with a large sum for its increase. … Lent his aid very quietly, but none the less effectually, to needy and meritorious students; and steadily refused then, as he has ever since done, and now does, to accept a dollar of compensation. Nothing ever gave Mr. Cornell more encouragement than this. For ‘Goldwin’ as he called him in his Quaker way, there was always a very warm corner in his heart.”

In that summer trip, White met Law in July. Immediately he wrote to Cornell: “As you know I have looked through the principal agricultural and veterinary colleges of Europe before arriving here. I have found several excellent candidates, but I find Mr. Law vastly their superior. He has published books and articles which have given him a high reputation on this side of the water and personally he is everything we could desire. Modest, unassuming, quiet, clear in his statements, thorough in his work. He cannot fail to succeed.”

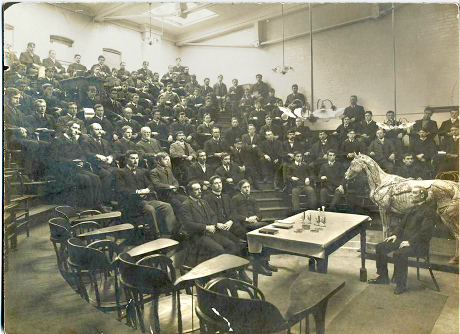

Indeed, Law did not fail to succeed. By August, Law traveled by steamer to the United States. He incorporated unprecedented standards – such as a bachelor’s degree and two additional years of doctoral education for veterinary medicine – to create America’s first veterinary college, which was formally established by 1894. A mere eight years after the university opened its doors, Cornell graduated its first veterinary student – in fact, the first veterinary doctor ever to graduate in the United States. His name: Daniel Elmer Salmon. Think Salmonella.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe