Even after having 'read a book,' one still judges it by its 'cover'

By Susan Kelley

A well-known saying urges people to “not judge a book by its cover.”

But people tend to do just that – even after they’ve skimmed a chapter or two, according to Cornell research.

Vivian Zayas, associate professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences, and her colleagues found that people continue to be influenced by another person’s appearance even after interacting with them face-to-face. First impressions formed simply from looking at a photograph predicted how people felt and thought about the person after a live interaction that took place one month to six months later.

“Facial appearance colors how we feel about someone, and even how we think about who they are,” said Zayas, an expert in the cognitive and affective processes that regulate close relationships. “These facial cues are very powerful in shaping interactions, even in the presence of other information.”

The research suggests we bring our assumptions about others into our interactions with them, she said. “If we’re not finding common ground with someone, or maybe there’s a little conflict, we have to ask ourselves, ‘What am I bringing into that interaction?’

“We often think that our perceptions of others are real, as real as the sun, instead of realizing that sometimes our perceptions might not be completely correct,” she said.

The study, “Impressions Based on a Portrait Predict, 1-Month Later, Impressions Following a Live Interaction,” is in press in Social Psychological and Personality Science. Co-authors are Gul Gunaydin, Ph.D. ’13, of Bilkent University in Turkey, and Emre Selcuk, Ph.D. ’13, of Middle East Technical University, also in Turkey. Both collaborators were Cornell graduate students in the Department of Psychology.

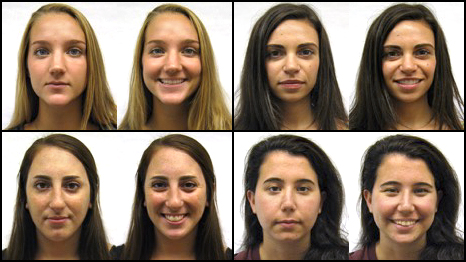

The researchers ran experiments in which 55 participants looked at photographs of four women who were smiling in one instance and had a neutral expression in another. For each photo, participants evaluated whether they would be friends with the woman, indicating likeability, and whether or not her personality was extroverted, agreeable, emotionally stable, conscientious and open to new experiences.

Between one month and six months later, the study participants met one of the photographed women – not realizing they had rated her photograph previously. They played a trivia game for 10 minutes then were instructed to get to know each other as well as possible for another 10 minutes. After each interaction, the study participants again evaluated the person’s likeability and personality traits.

The researchers found a strong consistency between how the participants evaluated the person based on the photograph and on the live interaction.

If study participants thought a person in a photograph was likeable and had an agreeable, emotionally stable, open-minded and conscientious personality, that impression carried through after the face-to-face meeting. Conversely, participants who thought the person in the photograph was unlikeable and had a disagreeable, emotionally unstable, close-minded, and disagreeable personality kept that judgment after they met.

“What is remarkable is that despite differences in impressions, participants were interacting with the same person, but came away with drastically different impressions of her even after a 20-minute face-to-face interaction,” Zayas said.

Zayas has two explanations for the findings. A concept called behavioral confirmation or self-fulfilling prophecy accounted for, at least in part, consistency in liking judgments. The study participants who had said they liked the person in the photograph tended to interact with them face to face in a friendlier, more engaged way, she said.

“They’re smiling a little bit more, they’re leaning forward a little bit more. Their nonverbal cues are warmer,” she said. “When someone is warmer, when someone is more engaged, people pick up on this. They respond in kind. And it’s reinforcing: The participant likes that person more.”

Regarding why participants showed consistency in judgments of personality, a halo effect could have come into play, she said. Participants who gave the photographed person a positive evaluation attributed other positive characteristics to them as well. “We see an attractive person as also socially competent, and assume their marriages are stable and their kids are better off. We go way beyond that initial judgment and make a number of other positive attributions,” Zayas said.

In a related study, she and her colleagues found that people said they would revise their judgment of people in photographs if they had the chance to meet them in person, because they’d have more information on which to base their assessment.

“And people really think they would revise,” she said. “But in our study, people show a lot more consistency in their judgments, and little evidence of revision.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe