Landscape architecture students take notes on a tour of Coney Island in September, as they conjure ideas to keep it from becoming uninhabitable due to sea level rise.

Saving Coney Island from the roller coaster of climate change

By Blaine Friedlander

Through the lens of natural history, Coney Island features marshes, wetlands, creeks and a sandy shore. Today, it’s famous for hot dogs, crowded beaches, Mermaid Avenue and Luna Park.

As sea levels rise, the Coney Island peninsula is in danger of becoming uninhabitable.

Cornell landscape architecture graduate students are wrestling with the island’s tenable, livable resilience in the face of nature aiming to reclaim it.

“Sea level rise isn’t something that we can stop, but it is something we hope we can work around,” said graduate student Eve Anderson. “It’s easy to say that in 2070, we should just abandon Coney Island and turn it into a floodable beach park and have no one live there. But the reality and question is – where will people go to live? What kind of livelihood can they have?”

Major parts of the island are only three feet above sea level, according to flood maps. The students say a four-foot ocean rise could occur as early as 2070 and a five-foot ocean rise may be at hand in 2100, which would put huge chunks of the iconic neighborhood under water.

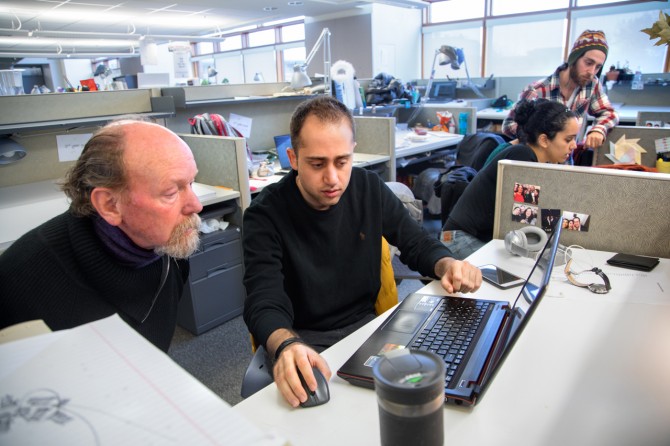

By semester’s end of the theory and practice course taught by Peter Trowbridge, professor of landscape architecture, and Mitch Glass, visiting critic in city and regional planning and landscape architecture, 36 graduate students will develop 36 ways to keep Coney Island inhabitants happy.

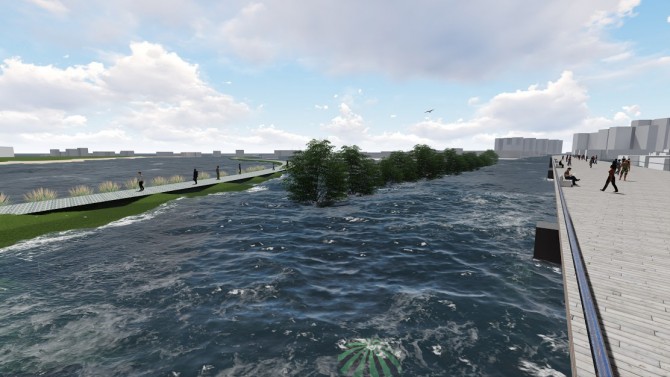

Since August, the class has been collecting data, scouring flood maps, analyzing sites, mocking up concepts and sketching transportation and circulation ideas. The students sort through a landscape architect’s toolbox: tidal barriers, walking or open space, breakwaters and new green technology.

Trowbridge and Glass took the entire class on a muddy, sandy, weedy hiking tour of Coney Island early in the semester, throughout which all students give presentations, absorb instructor critiques and idea tweaks. All of the students’ proposed solutions will be provided to Pamela Pettyjohn, president of the Coney Island Beautification Project, a group that can advocate for project implementation, said Trowbridge.

Anderson breaks her ideas into three phases covering the next 100 years. Her first phase addresses community issues, such as the chemically contaminated waters of Coney Island Creek that run below the bridges at Cropsey and Stillwell avenues – a gunky quagmire qualifying for superfund site status. After cleaning it up, Anderson suggests uncapping the creek to let it flow again to Sheepshead Bay. She then proposes to shift and reorganize the island population’s “center of gravity” – getting them to higher ground.

“I'm optimistic that innovation in the future will help mitigate the effects of climate change, slow it down and allow communities time to adapt,” said graduate student Joaquin Brito, who seeks to improve quality of life for the residents by turning vacant lots into pocket parks before residents are forced out. His plan calls for relocating islanders to higher ground currently occupied by parks.

“It is not too common to develop on parks,” he said. “The studio gives us a complex, tangible challenge and I hope our designs and suggestions can help.”

Trowbridge said that for over a decade, the class has participated in projects in the New York City metro area, including Jamaica Bay and Staten Island. After working all semester, the students will deliver their final Coney Island presentations in Ithaca on Dec. 4-5.

“The intent is to get students engaged in real-life, real-time projects which consider sea level rise, catastrophic flooding – like Superstorm Sandy – with responses that may lead to green infrastructure, out-migration of threatened and vulnerable populations, storm surge protections and other shoreline strategies,” Trowbridge said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe