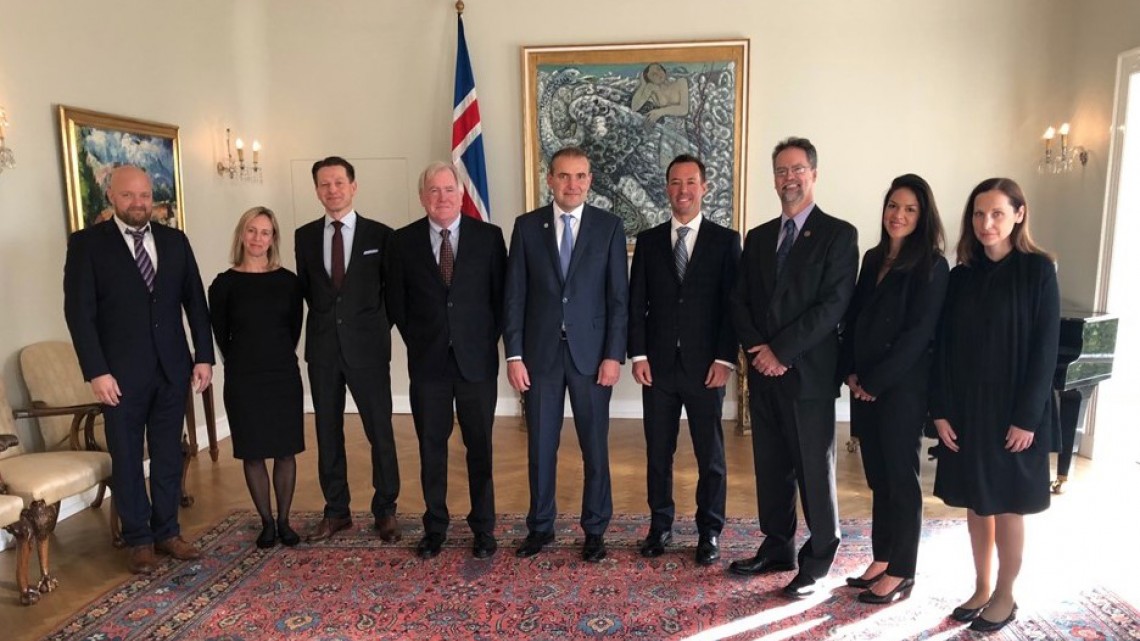

From left, Ingvar Eyfjörð Jónsson with Aðaltorg ehf; Kristin Kleisner with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF); Ríkharður Ibsen, director of Geothermal Resource Park; Patrick Sullivan, professor and department chair of natural resources; President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson; Merrick Burden with EDF; Richard Stedman, professor of natural resources; Crystal Franco with EDF; and Verena Jauss, postdoctoral researcher in natural resources.

Cornell-EDF team looks to Iceland fisheries for sustainable insights

By David Nutt

As Iceland goes, so goes the world?

Perhaps when it comes to sustainable fisheries management.

Thanks to its embrace of renewable energy, particularly geothermal heating, Iceland is a global leader in sustainability. Now a collaboration between Cornell and Environmental Defense Fund is studying the social, environmental and economic progress made by Iceland’s fisheries management system in the hope of creating a roadmap for sustainable development of marine resources worldwide that can withstand the ravages of climate change.

Fisheries are a major component of Iceland’s economy, feeding the population at home and exporting abroad. The country uses a rights-based fisheries management system, a sometimes-divisive practice in which individual quotas are assigned to vessels, resulting in reduced capacity, fixed supply and often more constructive and conservative fishing.

Geographically isolated, Iceland has essentially a closed system – one that is likely to be a bellwether for the effects of climate change – making it an optimal research subject, according to Patrick Sullivan, professor and department chair of natural resources, who is leading the project.

“Our work is really aimed at looking at this as an idealized case study to explore what would happen under various kinds of climate change,” Sullivan said. “Will it disrupt the system by bringing new species in or taking new species out? Will it affect the communities in terms of where the fish are? With this rights-based system, they can control the flow of the product. Maybe having these efficiencies in the system makes it more resilient, or maybe makes it more vulnerable. Those are the types of things we want to sort out.”

Cornell already has a strong connection with Iceland. In May 2016, the university signed a memorandum of agreement with Geothermal Resource Park (GRP) Iceland to design a renewable energy park on the university’s Ithaca campus. As that effort gained steam, project leader Jefferson Tester, the Croll Professor of Sustainable Energy Systems and director of the Cornell Energy Institute, reached out to Sullivan to see if there was anyone in the Department of Natural Resources knowledgeable about Icelandic fisheries management after Tester's Icelandic collaborators expressed interest in having someone affiliated with Cornell review the sustainability of their country's fishery practices

“I’ve been to Iceland several times to help with cod and general management systems, and I worked on special statistical techniques for doing acoustics and so forth,” Sullivan said. “I realized that if they needed somebody to do this, I was probably the one to do it.”

Sullivan connected with Richard Stedman, professor of natural resources and associate director for the Center for Conservation Social Science, as well as Senior Economist Merrick Burden and Senior Scientist Kristin Kleisner with Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit advocacy group with experience researching fisheries management in the North Atlantic.

With support from the David R. Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future’s Rapid Response Fund, the group traveled to Reykjavik in September to meet with potential collaborators and stakeholders: boat owners, seafood processers, union representatives, scientists with the Institute of Marine Research, academics with Reykjavík University, GRP Iceland and government officials, not least of whom were Iceland President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson and his advisers.

“The president was terrific,” Sullivan said. “He obviously recognizes how important fisheries are to his system. He’s very knowledgeable and open. He answered all our questions, even some of the more pointed ones. Everybody was willing to talk to us. That was overwhelmingly positive and made us think we could really do something there.”

Rights-based fisheries management is broadly used in the United States, particularly in the Pacific, as well as in New Zealand, Australia and a number of European countries. The researchers are hoping to determine whether it is transferrable to regions such as Indonesia and the Caribbean that have completely different fishery systems. They are also interested in exploring how small communities might be affected.

“These can be controversial in the sense that we take a public resource and give it to the fishermen,” Sullivan said. “It’s important to have the stakeholders involved in creating this, to get buy-in.”

The vast trove of data available through the Icelandic fisheries system means that Sullivan, a statistician, will be able to model various scenarios about how the changing climate might impact the ocean ecosystem, and how the potential loss of fish such as cod and capelin would ripple through Iceland’s economic market.

“Everybody talks about climate change, and you get this picture it’s getting warmer. But the real thing that’s happening is the circulation patterns in the ocean are changing. That’s really dramatic,” Sullivan said. “A change in weather conditions, like from El Nino, can create an upwelling; an upwelling brings up nutrients, that grows the fish. These things could be seen as benefits or perturbations. But they’re likely to react in ways that are not expected.”

David Nutt is managing editor for the Atkinson Center.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe