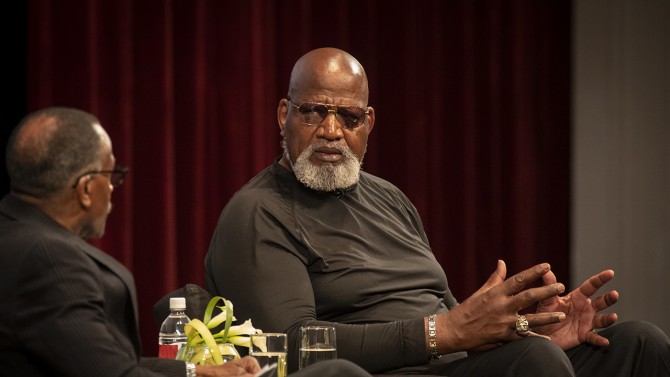

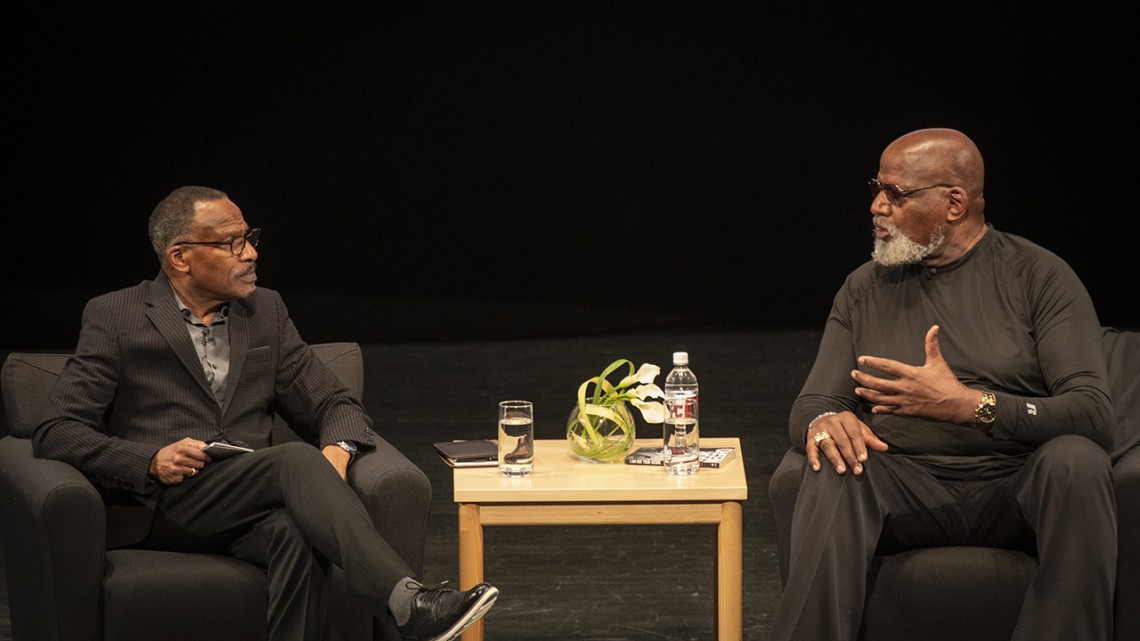

Frank Dawson, left, ’72, holds a public conversation in Bailey Hall with Harry Edwards, Ph.D, ’73, about the 1969 Willard Straight Hall occupation.

Alumni reflect on Willard Straight occupation, 50 years later

By Susan Kelley

On the 50th anniversary of a pivotal moment in Cornell’s history, two alumni returned to campus to offer insights not just as witnesses to that history but as participants in it.

Frank Dawson ’72 held a public conversation April 18 in Bailey Hall with Harry Edwards, Ph.D. ’73, about social justice and the 36-hour occupation of Willard Straight Hall.

Fifty years earlier, on April 19, 1969, dozens of members of Cornell’s Afro-American Society and several Latino students occupied the building to call attention to what they perceived as the university’s hostility toward students of color, its student judicial system and its slow progress in establishing an Africana studies program.

The occupation cannot be divorced from the civil rights movement that was playing out on the national stage, Dawson said. “We had seen the issues that our parents’ generation and their parents had to deal with,” he said. “We felt a responsibility to make some change on our own part as well.”

Dawson, now dean of career education at the Center for Media and Design at Santa Monica College, participated in the occupation as a first-year student. Edwards, one of the nation’s pre-eminent observers and scholars on the experience of black athletes and a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, was then a sociology doctoral student and played a prominent role in the Barton Hall teach-in that followed. At the Bailey Hall event, they reflected on the occupation, its cultural context and social justice past and present.

A national landscape of social unrest

Prior to the occupation, Edwards was immersed in the civil rights movement. He had interviewed Malcolm X for his master’s thesis on black Muslim families. He had worked with Martin Luther King Jr., belonged to the Black Panther Party and was close friends with Angela Davis and Stokely Carmichael. Then the assassinations began – of Malcolm X, King, 20 members of the Black Panthers and many other African-American civil rights leaders.

The students occupying the Straight were well aware of those deaths and the violence that others had experienced for their activism, Edwards said. Student protests were common at Cornell and elsewhere, but African-American students were told their protests were unwelcome, Dawson said. “Our position was, we have to be loud because otherwise we will not be heard.”

Participation in social justice protests took a toll on Cornell students. After the occupation, Dawson and some of his classmates never made it to Barton Hall for the teach-in. “We got out of town and went to the Penn Relays, just to decompress. It was that emotional,” he said. Many who participated in the occupation felt they had to leave Cornell afterward, he said.

“There’s always a cost that’s involved,” Edwards added.

Social justice, past and present

Earlier in the day, they had talked with current Cornell students, whom Edwards characterized as “bright, committed, strong, purposeful.” They deal with serious racial injustice every day as African-Americans, Edwards said. “The struggle continues, and these young people are wrestling with that,” he said.

Progress has been made, such as the record number of people of color elected in state and national elections, they agreed. There’s been progress on the Cornell campus as well – including the fact that they were there, commemorating the occupation.

“A number of years ago, maybe I wouldn’t have believed that this was going to happen. So give credit where credit is due, in terms of the evolution of this university,” Dawson said. “There’s still a lot that needs to be done, but at least we’re having conversations, which are important.”

When an audience member asked whether they would have done anything differently during the occupation, Dawson said no. The occupiers in the Straight during those 36 hours did not always agree, he noted. “One of the things I’m proudest of is that no matter what issue we had to deal with – and there were a lot of issues in that building – we were able to come to a consensus,” he said. “… It was a real lesson for me, which is why I say I really appreciate my education at Cornell, but I learned more outside the classroom than I did in the classroom in terms of my future growth and who I was to become.”

Another point that must be emphasized, Edwards added, is the inability of the administrators 50 years ago to understand the difficulties the African-American students faced on campus at that time. “It wasn’t meanness. They just couldn’t hear you,” he said. True education occurs only when students have the support services they need and an inclusive campus climate that nurtures them, he said.

In response to a question about freedom of speech on campus, Edwards said that the key to understand differing points of view is ongoing dialogue. “But you can’t start at the point of crisis,” he said. “It’s got to be every day. It’s got to be a cultural style. It’s got to be embedded in how you do business on a day-to-day basis.”

The discussion was one of several events taking place April 16-24 commemorating the 50th anniversary of the occupation. Additional events are being scheduled for Homecoming Weekend, Oct. 4-5.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe