The largest piece of undeveloped shoreline in the Finger Lakes, known as Bell Station in Lansing, New York, is the latest acquisition of the Finger Lakes Land Trust, founded by Andy Zepp, ’85, M.P.S. ’90.

Finger Lakes Land Trust, once a master’s project, conserves 28K acres

By Susan Kelley, Cornell Chronicle

The project seemed doomed.

For years, the Finger Lakes Land Trust had been working to preserve a 480-acre expanse of streams, waterfalls, mature forested hillsides and open fields alongside Cayuga Lake in Lansing, New York – the largest piece of undeveloped shoreline in the Finger Lakes. Now the land was up for auction to the highest bidder – and at risk for becoming clogged with private cottages.

“A guy called me up who is a billionaire; he just wanted to possess this,” says Andy Zepp ’85, M.P.S. ’90, executive director of the land trust, which began as his Cornell master’s degree project in 1989. “We knew if the land trust went to auction, we would likely be outbid. After a decade of working on this project, we thought it was gone.”

Instead, Zepp and his colleagues led a campaign to partner with New York state and acquired the land from its owner, New York State Electric & Gas, on May 24. In 12 to 18 months, the land trust will sell the parcel, known as Bell Station, to the N.Y. Department of Environmental Conservation, which will manage it for hiking, cross country skiing, wildlife watching, hunting and fishing. About 200 acres may be used for solar energy production.

“These last parcels are so important, because 90% of the shoreline on Cayuga Lake is developed and also inaccessible to the public,” Zepp says. “In the winter, you see bald eagles and waterfowl, flocks of migratory ducks. It’s really full of life.”

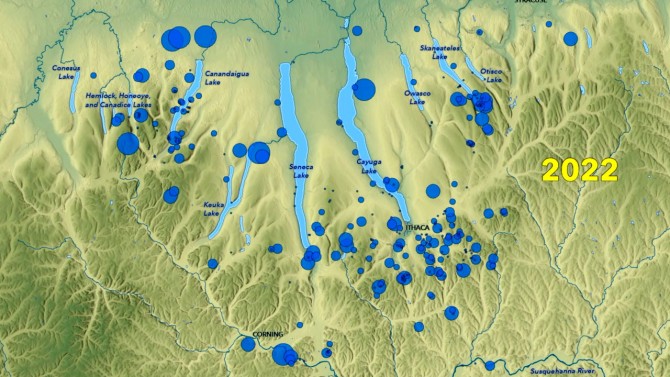

With Bell Station, the land trust now protects 28,730 acres of forests, farmlands, gorges and shorelines in the Finger Lakes. It creates public nature preserves and helps conserve their properties in 12 counties, an area about the size of Vermont, making it among the state’s larger land trusts.

Zepp’s motivation stems from a love of being outdoors – and his Westchester County upbringing. “It was a nice suburb, but nature was pretty much driven out,” Zepp says. “I saw we can do a much better job of balancing development and conservation. We have to.”

Cornell provides crucial support to the land trust’s activities, Zepp says. Faculty members advise on issues from land management to climate change. Students intern and volunteer. Fred Van Sickle, vice president for Alumni Affairs and Development, is the incoming president of the board; John Fitzpatrick, former longtime director of the Lab of Ornithology, has served on the president’s council for several years. “There are just many, many ways that we benefit both from the expertise of the university and the commitment of folks in Ithaca,” Zepp says. “They’re very much committed to the work we’re doing.”

A resounding yes

Zepp’s interest in conservation bloomed at Cornell. “I came as an undergraduate to Ithaca and the Finger Lakes and fell in love with the landscape,” he says. After majoring in organizational behavior at the ILR School, he worked for The Nature Conservancy in Connecticut and Western New York. “I saw areas that were really suffering – not from development per se, but from poorly planned development,” he says.

That motivated him to take a leave of absence from The Nature Conservancy and return to Cornell to pursue a master’s degree in natural resources at the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He helped create the land trust as his thesis project.

He networked for several months to recruit members of the community who might serve as the first board of directors, while he took classes in environmental law, forest ecology and soil sciences. He invited key recruits to gather one evening in 1988 in a Fernow Hall lecture hall, where Zepp provided information on how land trusts work.

“The question was, should they form a land trust? The answer was a resounding ‘Yes,’” Zepp says.

The first project the land trust initiated was Sweedler Preserve at Lick Brook in Ithaca, providing public access to one of the area’s most notable waterfalls. “You’re standing there, at this beautiful spot that’s one mile from downtown – it was the awareness that if you didn’t actively conserve it, there’s no way it would stay that way,” Zepp says.

After spending seven years as vice president for programs at the Land Trust Alliance, an umbrella organization for land conservation groups, Zepp returned to the Finger Lakes Land Trust in 2003 to serve as executive director.

The land trust now manages more than 45 nature preserves, acquiring land and opening it to the public. The preserves range from Richford in Tioga County in the east to Naples in Ontario County, to the west. Ten more projects are nearing completion.

A beautiful piece of woods

The land trust also partners with local, state and federal governments and other nonprofits to be a catalyst for projects like Bell Station.

And it uses a flexible tool called a conservation easement, to help private land owners limit development on their land in a way that is tailored to their needs.

Bob Good added a conservation easement to his 55 acres of woodlands in Springwater, New York, so it can never be subdivided or developed. The easement gives him peace of mind because the land is so closely tied to his family’s traditions and history. “Running into the land trust was a real godsend for me,” Good says.

He and his wife, Sue, now deceased, bought 12 acres in the early 1980s and added to it over time. They began camping on the land in a Boy Scout tent when their two daughters were babies. Eventually they built a cabin overlooking the valley. They named it Tommy’s Camp after Sue’s brother, who died as a young man in a motorcycle accident while studying to become a forester. Bob and Sue’s daughters and grandchildren visit the land frequently. Sue’s ashes are buried on the property, in an open field at the base of a red maple.

“I would hate the thought that someday this could all be divided up into 3-acre lots and turned into McMansions,” Good says. “We’re hoping that in 100 years or more, it’ll be a beautiful piece of woods still.”

And the easement plays a significant role in protecting Rochester’s drinking water. The property includes a rapid stream known as Reynolds Gull, which drains into Hemlock Lake, the source of Rochester’s water supply.

Water quality is the biggest challenge currently facing the Finger Lakes, Zepp says. “We’ve recently had outbreaks of toxic algae or cyanobacteria that are a huge concern, both for public drinking water supplies, but also for a region that has a $2 billion tourism economy that’s largely based on the lakes.”

The land trust has begun prioritizing projects that not only conserve land but also water quality, through two strategies. It works with lake associations and local governments to restore wetlands and straightened streams. And it secures lands that, if developed, would profoundly compromise water quality – such as the waterfall near the Bell Station shoreline. “If you look up at the steep slopes, if these were cleared for development, they would likely lead to more nutrient inputs into the lake,” he said.

Standing at the Bell Station shoreline, he points out mature oak, maple, elm and ash trees that shade the dappled water, and the invasive plants like privet and honeysuckle that have started to take over – another serious challenge facing the Finger Lakes. “I can’t get away from, ‘Oh my God, that shouldn’t be here,’” he says. “What I’m always thinking about is maintaining and enhancing diversity.

“I visit preserves all the time and I’m always thinking about how can we up our game. I just can’t help thinking, ‘With a few more resources, what would we do next?’”

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe