Underwater 3D printing could transform maritime construction

By David Nutt, Cornell Chronicle

Since it was invented in the 1980s, 3D printing has moved from the laboratory to the factory, the home and even outer space.

Now, an interdisciplinary group of Cornell researchers is developing a way to bring the technology to the ocean. By 3D-printing concrete underwater, the new approach could transform on-site maritime construction and the repair of critical infrastructure that connects continents.

“We want to be constructing without being disruptive,” said Sriramya Nair, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering in the David A. Duffield College of Engineering, who leads the effort. “If you have a remotely operated underwater vehicle that shows up on site with minimal disturbance to the ocean, then there is a way to build smarter and not continue the same practices that we do on the land.”

The project got its start in fall 2024, when the Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) issued a call for proposals to design 3D-printable concrete that could be deposited at a depth of several meters underwater – and to do so in a radically truncated timeframe of one year.

“When the call for proposals came out, we said, ‘Hey, let’s just do this and see, so that we will at least understand what the challenges are,” said Nair, whose group had already been working with a roughly 6,000-pound industrial robot to 3D-print large-scale concrete structures. “And it turned out, with our mixture we could actually 3D-print underwater by making adjustments to account for continuous water exposure.”

In May 2025, the team was awarded a one-year, $1.4 million grant that is contingent on meeting certain benchmarks, with five other teams competing to do the same.

Underwater printing faces numerous challenges. Chief among them is preventing washout, in which cement particles fail to bind together during deposition, weakening the material. The typical solution is introducing admixture chemicals, but these create complications of their own.

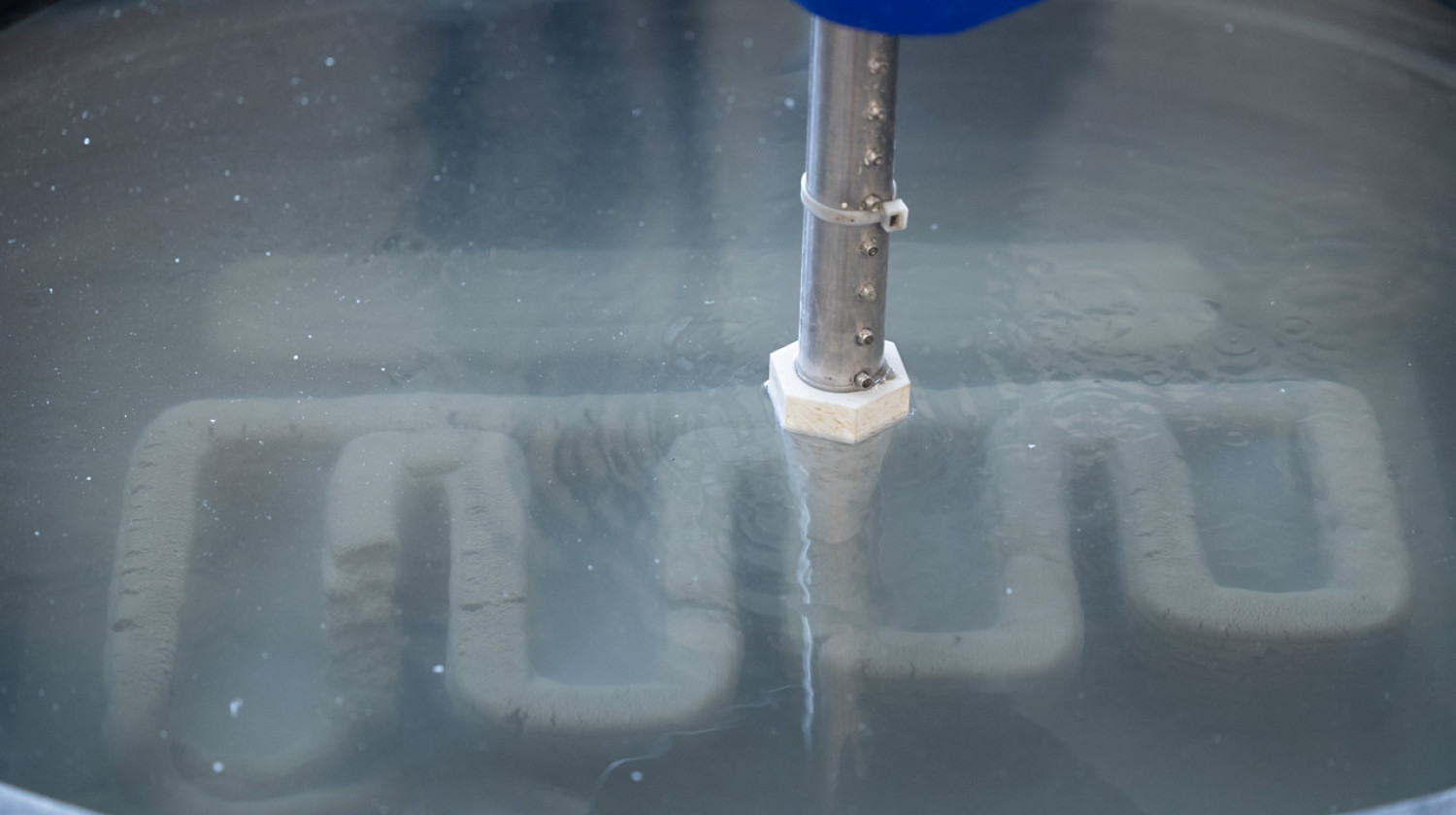

For months, the team has been conducting test prints in a large tub of water, monitoring how the layers are deposited and the strength, shape and texture of each sample.

“When you add those chemicals, it makes your mixture really viscous, and you can’t pump. So you’re balancing that pumpability with these anti-washout agents,” Nair said. “When it extrudes, even if you don’t have washout, you still want it to be able to hold the shape and bond well with the other layers. There are multiple parameters at play.”

DARPA added one more hurdle: The concrete needed to consist primarily of seafloor sediment and only include a small amount of cement. Incorporating material from the bottom of the ocean would minimize the logistical difficulty of transporting large quantities of cement by ship.

In September, the Cornell team successfully demonstrated to a group of visiting DARPA officials that they were getting close to meeting the agency’s high sediment target. It was a huge milestone, according to Nair.

“Nobody is doing this right now,” she said. “Nobody takes seafloor sediment and prints with it. This is opening up a lot of opportunities for reimagining what concrete could look like.”

The complexity of underwater 3D printing requires a range of specialized knowledge, so Nair assembled an interdisciplinary group with two sub-teams, one for material design, the other fabrication. Collaborators include: Nils Napp, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, Greg McLaskey, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, and Uli Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Engineering, in materials science and engineering; Jenny Sabin, the Arthur L. and Isabel B. Weisenberger Professor in Architecture in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning; as well as researchers from University of Michigan, Clarkson University and University of Arizona.

The second phase of the DARPA challenge will culminate in a bake-off of sorts, with multiple teams 3D-printing an arch underwater, in March. For months, Nair’s team has been conducting test prints in a large tub of water – often producing multiple samples every week – in the Bovay Civil Infrastructure Laboratory Complex. The lab setting allows the researchers to closely monitor how the layers are deposited and the strength, shape and texture of each arch. But that kind of tactile assessment is only possible on dry land.

“Let’s say you want to print underwater in the real world – we can’t send somebody down with a scuba suit, right? We have to be able to detect those things and adjust our tool path in real time,” Nair said. “The overall goal is to achieve good print quality, because if you don’t place your material where it needs to be, you’re not going to get the strength you need.”

So in lieu of scuba divers, the fabrication team set out to design sensors that can track the printing as it occurs. Marine conditions don’t make the process easy.

“The problem is sediment is super fine, and as soon as you stir it up, you can have zero visibility,” said Napp, who specializes in building and programming mechatronic devices that navigate and modify unstructured environments. “We didn’t know how much turbidity – or murkiness – there would be in the water.”

So Napp’s group designed a control box with multiple sensing systems that can be integrated with the robot arm. This device will be paired with Sabin’s work in robotics to bring greater autonomy and control to underwater concrete printing.

The DARPA competition’s final demonstration will be held in March, and the team is racing to incorporate the advances made by the fabrication team with those of the materials team to successfully print the arches.

While the accelerated pace and high-pressure nature of the competition can be tough on the nerves, the urgency has helped make the team as productive as possible.

“As soon as the grant was awarded, we were all meeting once a week, trying to make progress,” Napp said. “It’s a pretty ambitious timeline, and it’s cool to see so many different areas of expertise coming together quickly and pushing this forward.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe