News directly from Cornell's colleges and centers

Programmable plant sprint hits the ground running

CROPPS showcases closed loop fertigation system controlled by the plants themselves

By

When a team of biologists, engineers, and computer scientists gathered across the Cornell campus in January, their goal was ambitious but concrete: by the end of the sprint, build and demonstrate a fully functioning, closed-loop system in which plants could sense their own nitrogen status and automatically trigger a nutrient system to correct it.

By the end of the CROPPS Spring 2026 Sprint, they had done exactly that.

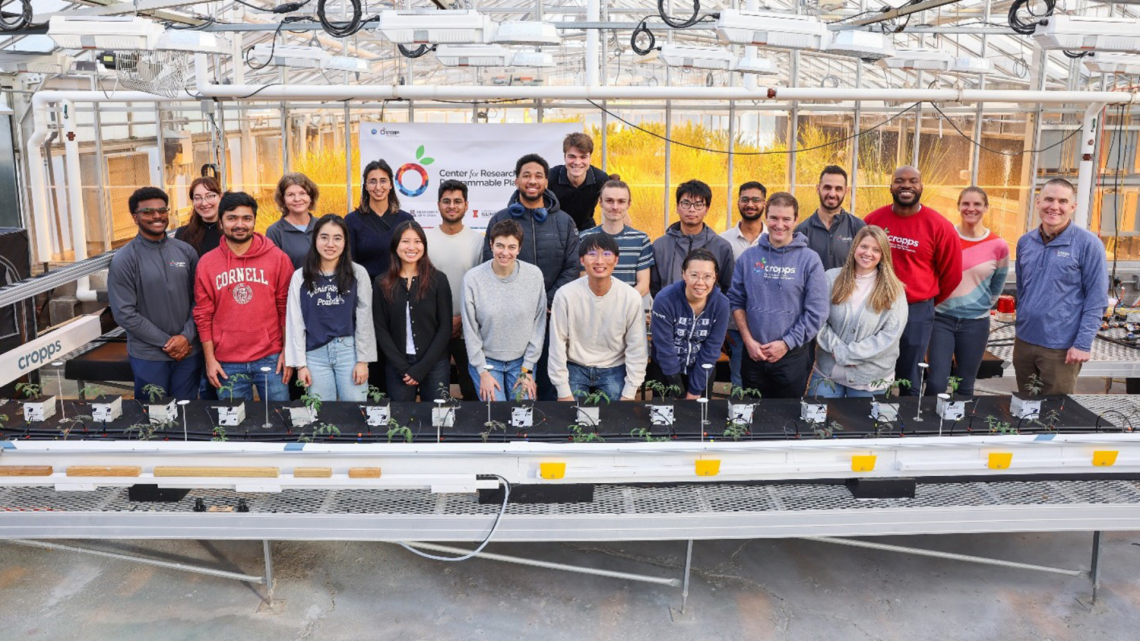

Hosted by the Cornell Center for Research on Programmable Plant Systems (CROPPS), the week-long working session brought together members of the CROPPS team from multiple institutions and academic disciplines to accelerate progress on one of the Center’s core research goals – developing programmable plants that can respond to their environment and communicate their needs.

The sprint culminated in two live demonstrations by CROPPS trainees, who are doctoral students, postdoctoral associates, and early career researchers supporting the CROPPS mission. Demos showcased a closed-loop prototype built around the RedAlert tomato plant, a genetically engineered nitrogen reporter created by the CROPPS team. The RedAlert exemplar (model) plant’s leaves change color as nitrogen levels fluctuate, shifting from healthy green to red under nitrogen stress.

For the demonstration, robotic cameras monitored the plants while linked to custom-built color-sensing imaging software. The software then analyzed the images in real time and quantified the color shift, and the biological signal was input to an automated decision-making pipeline. A "RedAlert", indicating deficient nitrogen, then triggered a microcontroller to adjust nitrogen delivery through the fertigation (irrigation + fertilizer) system. As nitrogen levels are restored, the plants then return to green in a few days, restarting the cycle.

“This wasn’t just a demo, it was also a proof of concept for how we train the next generation of scientists to work together on complex, real-world problems,” said Elizabeth Jones, director of research for CROPPS. “And we’re addressing issues that farmers face daily, reducing the cost of fertilizer inputs and the environmental impact of growing food for a hungry nation.”

“The problem we’re working to solve is enormous,” said Jacob Belding, a senior CROPPS trainee and graduate student in Cornell Duffield Engineering. “A huge percentage – estimates range from 40%-80% – of the fertilizer that American farmers apply to their fields is never taken up by the plants. The remaining nitrogen becomes runoff, poisoning groundwater, and surface waterways. This isn’t carelessness: without a better source of information on the real-time needs of our crops, we are forced to continue using nitrogen wastefully. We built RedAlert to change this by providing that crucial information.”

“Being in Year 5 of our organization, CROPPS, undoubtedly, was moving toward a closed-loop programmable plant system,” said Darius Melvin, assistant director of engagement and partnerships for CROPPS. “If we could bring the right mix of personnel and structure to the Sprint, we would not only have a good chance of developing a closed-loop system but also create an effective, convergence research experience. Therefore, every detail of the sprint was intentional, from selecting the trainee leads, to keeping flexibility with our workflow, to when and what we ate for our meals.”

That focus paid off during the final demonstrations. Over two live sessions, CROPPS trainees showed how the system could detect nitrogen stress, analyze plant signals, and autonomously deliver a nutrient dose without human intervention. Visitors, including Cornell staff and faculty, observed the system operating in real time, closing the loop from plant signal to automated response.

Trainees led every project team, a structure that organizers say reflects CROPPS’ commitment to transdisciplinary training. Belding, a doctoral associate in the lab of Abraham Stroock, Gordon L. Dibble '50 Professor in the R.F. Smith School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, led the overall closed loop sprint deliverables. Meagan Lang, a postdoctoral associate from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, worked alongside Noor AlBader, a postdoctoral associate from the Boyce Thompson Institute, in developing software tools to model and analyze the spatial and color information gathered by the imaging gantry, the overhead robot holding digital cameras.

Shuangyu Lei and Salman Abid, doctoral students in the Cornell University Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, programmed the dashboard interface for working with “CoRA” (which comes from “CROPPS RedAlert”), the automated gantry robot system. They tied in communications with the hydroponic system microelectronics, implemented the image analysis pipeline and set up a live feed from the CROPPSpace “SkyCam.”

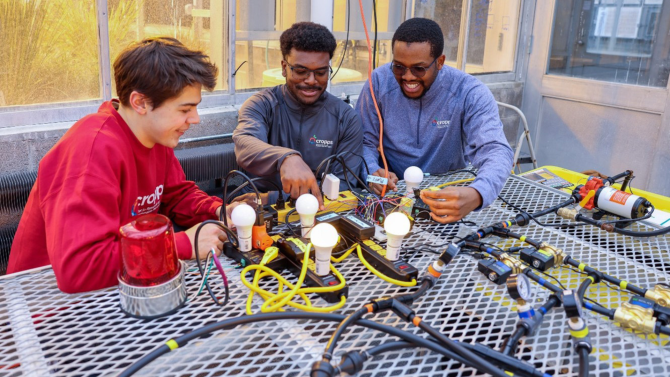

The plant team was led by Tian Gong, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Margaret Frank, associate professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. She led the team transplanting the exemplar plants from a bespoke bucket system into commercially available hydroponic rockwool, and labeling and cataloging the collection of test plants into the system. Daniel Baldeo-Thorne, a recent graduate of Cornell who participated in Rev’s Summer Prototyping Hardware Accelerator program, worked with Bobby Henkelmann, an undergraduate student in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering and a member of the Cornell Autonomous Underwater Vehicle project, on the wiring and programmable microelectronics that actuate the pumps and valves of the hydroponic fertigation system.

Amidst all this hardware, software and plant activity, Nathaniel Ponvert and Austin Frisbey, both postdoctoral associates from the University of Arizona School of Plant Sciences, gave a seminar presenting on how plants use long-distance signaling waves to coordinate stress responses, and sense soil nitrogen via CEPR1 signaling and reveal nitrogen status. And, a second sprint team developed a separate, portable demonstration unit called “CROPPS in a Box.”

By placing trainees in leadership roles and structuring teams around shared deliverables rather than disciplines, the sprint created space for new collaborations and mutual learning, Jones said. Engineers gained a deeper understanding of biological constraints, while plant scientists engaged directly with data pipelines, control systems, and hardware design. Many participants reported that the experience reshaped how they think about collaboration and problem-solving across fields.

“Going from a collection of siloed systems,” Belding said, “some of them just ideas, and taking that all the way to a fully integrated demonstration system over the course of only three days was incredibly thrilling. Especially watching the excitement build within the team as more of our components came online. Knowing that we would soon hand over this ‘button clicking’ control to a plant was awe-inspiring.”

Henry C. Smith is the communications specialist for Biological Systems at Cornell Research and Innovation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe