Dying to be heard, Africa's forest elephants are targets of large-scale acoustic monitoring effort

By Roger Segelken

Biologists and acoustic engineers based at Cornell will join researchers at two sites in Africa in a new program to monitor the numbers and health of forest elephants by eavesdropping on the sounds they make.

New monitoring procedures will be tested in the Central African Republic, beginning in March 2000, and in Ghana in May 2000 before expanding to other regions of the continent.

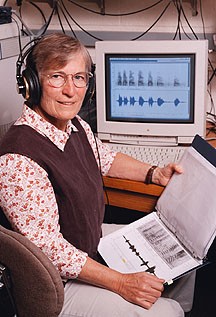

"Acoustic monitoring may give us crucial information on the elephants about which we know almost nothing because they live under the cover of forests," explains Katharine B. (Katy) Payne, a research associate in the Bioacoustics Research Program of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

"With the increasing pressure on African elephants from the ivory trade and from illegal poachers, we desperately need to know how many animals are still alive and what they're doing," says Payne, whose discovery of long-distance infrasonic communication among elephants is recounted in her book Silent Thunder (Simon & Schuster, 1998).

Says Christopher W. Clark, Cornell's I.P. Johnson Senior Scientist and director of the Bioacoustics Research Program, "When you're recording animal sounds you're also monitoring their physical environment, and this will provide insights to aspects of the elephants' behavior and ecology that are available in no other way." Clark's first demonstration of the feasibility of acoustic counting focused on whales. His laboratory pioneered the use of acoustic arrays for monitoring animals and developed computer-based tools, such as a program called Canary, for the measurement and analysis of natural sounds.

One unnatural sound that biologists would hate to hear -- and one that could be picked up by microphone arrays -- is the sound of poachers who kill the animals for their valuable ivory tusks, says Steve Gulick, a recording engineer who first captured the calls of forest elephants in Gabon and the Central African Republic. "If we can maintain real-time access to microphone arrays via satellite or radio, we can keep track of some very wide areas. That monitoring of elephant and human activity is not feasible now; we only find out about poaching activity after the carnage, when we're walking through the fields of carcasses."

Gulick was one of five Africa-based researchers to meet with Cornell scientists at the Laboratory of Ornithology in September to plan the acoustic monitoring. He said the survey eventually could be expanded to study -- and offer protection to -- other endangered animals such as gorillas and rhinos.

"We are moving into an era when wild populations that were considered as common commodities are being depleted, and we're confronted with the fact that we know very little about these populations," says John Hart, a survey planner whose long-term studies in forest environments are supported by the Wildlife Conservation Society. "How can decisions at any level be made about the management or trade in endangered species without some knowledge about these populations?"

Another survey planner, Richard Barnes, spent decades in Ghana making systematic counts of elephant dung piles to chronicle the animals' presence and abundance, and he believes that now is the time to attempt acoustic monitoring. "If we had some way of knowing when the elephants are moving up and down the valley, we could then get a handle on the reasons for that movement," Barnes says.

That is the question for researchers at the Cornell laboratory as they prepare for the 2000 survey. Using data-analysis programs that map a calling elephant's location from a four-microphone array, the researchers can tell exactly where the animal is. In past surveys researchers have been able to link an elephant's calls to its behavior and circumstances by watching simultaneously recorded videotapes. Other elephants' reactions to a call can be just as informative as actions of the calling animal itself, Payne notes.

But in the densely forested environments, researchers won't have the benefit of video surveillance. That is why Payne and two assistants are looking for clues in hundreds of hours of audiotapes and videotape of savanna elephants recorded in a previous season. Payne's study is showing that the rates and patterns of calling reflect the difference between small and large groups, and often reveal what is going on.

"Elephants are very noisy during mating, for instance, and the female usually makes a repetitious series of calls when she is mounted," Payne notes. "This will provide useful information in a monitoring program because reproduction is one of the clearest signs of a population's health." Some of the elephants' most information-rich calls are produced in the infrasonic range, which is too low for human hearing until the tape is speeded . Infrasonic calls are audible to other elephants miles away, allowing separated animals to find one another.

The sound data is eagerly awaited by Andrea Turkalo, who spent the last nine years documenting the demography and behavior of some 2,000 forest elephants in the Central African Republic. Most of her observations took place in a mineral-rich clearing called Dzanga-sanga. What the elephants do when they return to the forest -- and how many elephants are still to be counted -- remains a mystery that partly could be solved by the high-tech eavesdropping, Turkalo anticipates.

The first phase of the forest elephant acoustic monitoring is supported by a Species Action grant from World Wildlife Fund and is conducted at the Bioacoustics Research Program, a unit of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. During last month's gathering, which was sponsored by the Cornell laboratory, World Wildlife Fund, Wildlife Conservation Society and Conservation International, the prospective collaborators wrote proposals to fund the remaining phases.

Explaining why a bird lab is aiding elephants, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology Director John W. Fitzpatrick says: "Our mission explicitly acknowledges that we are here for the protection and interpretation of the Earth's biological diversity. All organisms, large and small, are linked. Elephants just happen to be one of the bigger links."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe