New device from CU physicist tests uncertainty principle to unprecedented level -- and shows that looks can cool

By Lauren Gold

In the submicroscopic world -- the domain of elementary particles and individual atoms -- things behave in the strange, counter-intuitive fashion governed by the principles of quantum mechanics. Nothing (or so it seems) like our macroscopic world -- or even the microscopic world of cells or bacteria or dust particles -- where Newton's much more reasonable laws keep things sensibly ordered.

The problem comes in finding the dividing line between the two worlds -- or even in establishing that such a line exists. To that end, Keith Schwab, associate professor of physics who moved to Cornell this year from the National Security Agency, and colleagues have created a device that approaches this quantum mechanical limit at the largest length-scale to date.

And surprisingly, the research also has shown how researchers can lower the temperature of an object -- just by watching it.

The results, which could have applications in quantum computing, cooling engineering and more, appear in the Sept. 14 issue of the journal Nature.

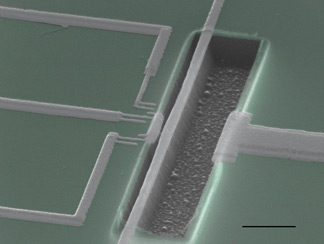

The device is actually a tiny (8.7 microns, or millionths of a meter, long; 200 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, wide) sliver of aluminum on silicon nitride, pinned down at both ends and allowed to vibrate in the middle. Nearby, Schwab positioned a superconducting single electron transistor (SSET) to detect minuscule changes in the sliver's position.

According to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the precision of simultaneous measurements of position and velocity of a particle is limited by a quantifiable amount. Schwab and his colleagues were able to get closer than ever to that theoretical limit with their measurements, demonstrating as well a phenomenon called back-action, by which the act of observing something actually gives it a nudge of momentum.

"We made measurements of position that are so intense -- so strongly coupled -- that by looking at it we can make it move," said Schwab. "Quantum mechanics requires that you cannot make a measurement of something and not perturb it. We're doing measurements that are very close to the uncertainty principle; and we can couple so strongly that by measuring the position we can see the thing move."

The device, while undeniably small, is -- at about ten thousand billion atoms -- vastly bigger than the typical quantum world of elementary particles.

Still, while that result was unprecedented, it had been predicted by theory. But the second observation was a surprise: By applying certain voltages to the transistor, the researchers saw the system's temperature decrease.

"By looking at it you cannot only make it move; you can pull energy out of it," said Schwab. "And the numbers suggest, if we were to keep going on with this work, we would be able to cool this thing very cold. Much colder than we could if we just had this big refrigerator."

The mechanism behind the cooling is analogous to a process called optical or Doppler cooling, which allows atomic physicists to cool atomic vapor with a red laser. This is the first time the phenomenon has been observed in a condensed matter context.

Schwab hasn't decided if he'll pursue the cooling project. More interesting, he says, is the task of figuring out the bigger problem of quantum mechanics: whether it holds true in the macroscopic world; and if not, where the system breaks down.

For that he's focusing on another principle of quantum mechanics -- the superposition principle -- which holds that a particle can simultaneously be in two places.

"We're trying to make a mechanical device be in two places at one time. What's really neat is it looks like we should be able to do it," he said. "The hope, the dream, the fantasy is that we get that superposition and start making bigger devices and find the breakdown."

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe