Cassava database becomes open access

By Linda McCandless

Six months after the launch of the $25.2 million Next Generation Cassava Breeding (NEXTGEN Cassava) project at Cornell in November 2012, its scientists have released a database that features its breeding data for open access data sharing, which means it is immediately available prior to publication.

Cassavabase includes all the phenotypic and genotypic data generated by cassava breeding programs involved in the project.

“In the plant breeding community, data-sharing can be delayed until publication, which can limit the opportunity to use the knowledge by the international plant breeding communities,” said database developer Lukas Mueller of the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research on the Cornell campus, and adjunct professor of plant breeding and genetics at Cornell.

Cassavabase and the advantages of open access data were presented at the G8 International Conference on Open Data for Agriculture in Washington, D.C., April 29-30, by Chiedozie Egesi from the National Root Crops Research Institute, Nigeria, a project partner and data contributor to Cassavabase.

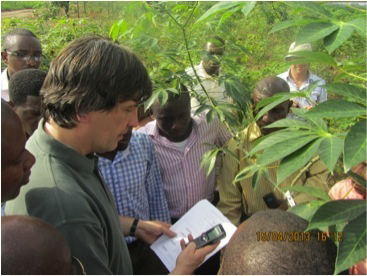

Researchers such as Peter Kulakow, plant breeder at the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture and a major contributor of data to Cassavabase, say that Cassavabase will lead to increased efficiency in agricultural research and ultimately improve the livelihoods of African cassava farmers. It will allow African farmers, for example, to benefit from the best technologies available to improve the yield and quality of cassava that they raise for food and income.

In 2012, G8 leaders implemented the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition with the aim of boosting agriculture production in six countries and lifting 50 million people out of poverty in 10 years. Critical to food security in developed and developing countries was the implementation of policies and projects to make data readily accessible to users in Africa and worldwide.

“Different versions of cassava genes can be found in all breeding programs. What one program learns about its genes can benefit everybody,” said Jean-Luc Jannink, lead scientist on the NEXTGEN Cassava Cassava project, research geneticist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and adjunct professor of plant breeding and genetics at Cornell. “All our learning is leveraged by sharing.”

Cassavabase provides a “one-stop shop” for cassava researchers and breeders worldwide. It also offers access to all genomic selection analysis tools and phenotyping tools developed by the NEXTGEN Cassava project. Project partners and donors envisage Cassavabase as a tool that will serve the whole cassava community, and that it will last beyond the lifetime of the NEXTGEN Cassava project.

No other continent depends on cassava to feed as many people as does Africa, where 500 million people consume it daily. Africa’s small farmers produce more than half of the world’s cassava. The tough plant requires few inputs and can withstand drought, marginal soils and long-term underground storage. A cash crop as well as a subsistence crop, the storage roots of the perennial shrub are processed, consumed freshly boiled or raw, and eaten by people as well as animals as a low-cost source of carbohydrates.

Despite diverse growing conditions and multiple uses of cassava across sub-Saharan Africa, farmers face similar challenges fighting cassava viruses and drought conditions that adversely affect yield.

The NEXTGEN Cassava project aims to use the latest advances in breeding methodology to improve productivity and yield in cassava production, incorporate cassava germplasm diversity from South America into African breeding programs, train the next generation of plant breeders, and improve infrastructure at African institutions.

NEXTGEN Cassava is supported the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Department for International Development of the United Kingdom.

For more information, visit http://www.nextgencassava.org.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe