Library displays '150 Ways to Say Cornell'

By Daniel Aloi

The ideals set forth for Cornell by its founders, Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, constituted a “truly radical educational experiment for the 1860s” and have made for an inspiring history, University Archivist Elaine Engst says.

How the notion of “any person, any study” shaped that history on the Ithaca campus and beyond is the basis of Cornell University Library’s new sesquicentennial exhibit, “150 Ways to Say Cornell.”

The exhibit, curated by Engst and Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections staff, runs through Sept. 30, 2015 , in the Hirshland Exhibition Gallery in Kroch Library. Original documents, photographs and artifacts are arranged in cases devoted to Cornell’s founding and other aspects of its history and campus life – women, international and minority students; protest movements; Cornell and the military; athletics; and the library, which was first wired for electricity in 1885.

The language in the Morrill Land Grant Act allowed for “agriculture, the mechanic arts, military tactics and whatever you want to teach,” Engst said. “So Cornell has always really tried to integrate the liberal and the practical. It was very important to both White and [Ezra] Cornell that all of the subjects would be treated equally.”

The display features the original charter – a bill signed by New York Gov. Reuben E. Fenton, April 27, 1865, in Albany. The charter clearly says any persons, of any religious denomination or of no religious denomination, could attend Cornell. By “persons,” Engst said, “they really did mean men and women.”

The governor was still in office but did not attend the inauguration of the university in 1868 “because it was a political hot potato. Andrew Dickson White annoted his inauguration program to say that Gov. Fenton was a friend of the Baptists and Methodists and other sectarian enemies of the university,” Engst said.

In 1873, Ezra Cornell said in a speech at the laying of the cornerstone of Sage Hall that he would “‘place a letter in the cornerstone … that tells the reasons for the failure of the experiment,’ if it ever fails,” Engst said. For over a century, no one but its author knew the contents of the letter, which is also on display.

In the 1990s Sage Hall was renovated and “we got to open the cornerstone,” Engst said. “I was the first to read [the letter], which was one of the high points of my life.”

She continued: “The letter was astonishing. Ezra Cornell had no question about coeducation; that was going to be just fine. It was the nonsectarian piece that was controversial, and he was convinced it was what would likely sink the university. For Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, the question wasn’t whether their students would be religious or not … it was that [they] could make that decision for themselves.”

Cornell had its first woman graduate in 1873, but “what dramatically increased the number of women was the Home Economics program [in 1907]. It was a very welcoming place for women students and even more so, for women faculty,” Engst said.

“‘Any person’ also means international students and minority students,” she said, indicating a book kept by Ezra Cornell, who “was very interested in where students came from, and he wrote it down. He wrote down students from every state and students from 11 foreign countries. In 1870 there were students here from Japan, Sweden, Serbia and Hungary, among other countries. Diversity was very important for the founders.”

Also on display are an enlargement of the McGraw clock tower building plan, the original Cornell seal, A.D. White’s lecture notes, a Harper’s Weekly layout showing Cornell in 1873 and a letter from Ezra Cornell to his 4-year-old granddaughter, encouraging her to attend Cornell.

Cornell memories

Cornell history comes in all shapes and forms, and for one class at least, it looks like a penguin.

Not content with a bear for a mascot, the Class of 1936 adopted the bird as its animal totem. The reasons why are lost to history, but other class mascots have included a cow, a pig, a dog and a frog. “They would use that symbolism in their class correspondence,” said library collections assistant Evan Earle ’02, M.S. ’14.

The penguin and a stuffed dachshund in Cornell colors are among some unusual memorabilia displayed in Kroch Library, curated by collections assistant Marcie Farwell. Items include a ‘Kitty Co-Ed’ doll in a Cornell sweater; a beanie and a mug from 1908; several medallions, pins and class rings; pipes, ashtrays and cigarette flannels bearing Cornell emblems; and ephemera from student scrapbooks such as tickets to lectures, dances and formals.

“I was trying to find those things that represent that box we all keep in the closet,” Farwell said. “We collect material from alumni on a regular basis; people don’t always know that we have objects here.”

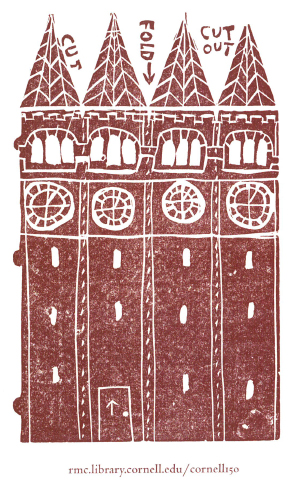

In the Risley Print Shop, Farwell came across a linoleum block of a cut-and-fold model of McGraw Tower that she used to print a promotional handout for the exhibition.

“Who made it?” she wondered. “We would love to give them credit.” (Email rareref@cornell.edu if you know.)

The hallway leading from Olin Library to Kroch offers more history, via a large illustrated timeline by library graphic designer Carla DeMello and enlargements of postcard images showing the campus over a century ago.

Hirshland Exhibition Gallery is open Monday-Friday, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. and during special Saturday hours, 1-5 p.m. through Nov. 22. Closed Sundays and Nov. 27-28.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe