Cornell Rewind: Exploring our world and beyond

By Elaine Engst and Blaine Friedlander

Cornell Rewind is a series of columns in the Cornell Chronicle to celebrate the university’s sesquicentennial through December 2015. This column will explore the little-known legends and lore, the mythos and memories that devise Cornell’s history.

Not long after Cornell University opened its doors, professors organized expeditions – and included students in those adventurous research sojourns. For 150 years, faculty and students have traveled to each continent and – in a way – around the solar system, as well.

These researchers have collected insects, plants, sounds, artifacts and photographs.

Geology professor Charles Frederick Hartt – one of Cornell’s first faculty members and a student of Harvard’s Louis Agassiz – became a principal in an 1870 expedition to Brazil. Hartt took 11 Cornell students with him. Before his death from yellow fever at the age of 38, he participated in three additional expeditions, collecting specimens for the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro and encouraging Brazilian students to attend Cornell.

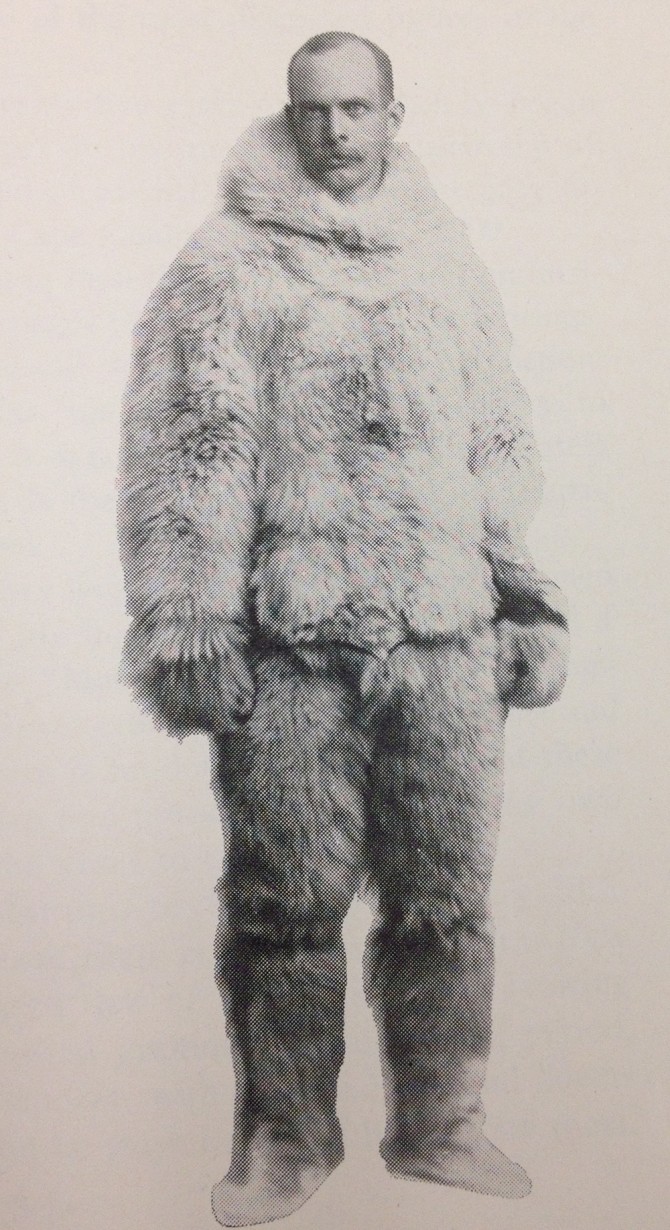

The New York Times covered professor Ralph Tarr’s research on an 1896 Arctic expedition around Greenland with then-Lt. Robert Peary. The Cornell party included A.C. Gill, professor of mineralogy; and students Thomas Leonard Watson (Ph.D. 1897), Edward Martin Kindle (M.S. 1896), Jay Allen Bonesteel (Class of 1896) and James Otis Martin (B.S. 1899, M.A. 1903).

In August 1896, the Times reported, as the Peary party and the Cornell party split up, the steamship Hope hung up on an ice floe along the Greenland coast. But “Prof. Tarr … does not intimate that the vessel is in any immediate danger,” said the Times. Professors and students continued their exploration and made it home safely in September. In 1906, Tarr accompanied Peary to the Arctic, naming a glacier in Greenland for Cornell, and undertook four expeditions to study glaciers in Alaska. His student and eventual colleague, O.D. von Engeln (Class of 1908, Ph.D. 1911) joined Tarr on expeditions in 1906 and 1909.

‘The news staggered me…’

Not every Cornell explorer was lucky: On his dash to North Pole in 1909, Cmdr. Peary brought Ross Gilmore Marvin, Class of 1905 – who had been a Cornell engineering instructor – to lead a supporting party. Marvin died under mysterious circumstances.

During the expedition, parties had broken up, and Marvin was with a group of Eskimos exploring the Arctic region. Peary learned of Marvin’s death from the Eskimos who had returned to the original Peary party.

“The news staggered me, killing all the joy I had felt at the sight of the ship and her captain,” recalled Peary, in his serial account in Hampton’s Magazine. Eskimos Kudlooktoo and Inukitsoq reported that Marvin had fallen through the ice.

Peary came to Ithaca in 1910 to give the address for Marvin’s memorial services at Sage Chapel, where a plaque his honor on the north wall of the chapel remains to this day.

Sixteen years later, while in the process of getting baptized, Kudlooktoo confessed a crime to a missionary: Marvin had not drowned accidentally; he was murdered. In the heat of an argument between them, according to one account, Marvin was shot and killed. In another version, Kudlooktoo said Marvin had to be killed because he had gone crazy and tried to abandon them on the ice. Others, including Peary’s daughter, discounted both accounts as “induced by religious hysteria.” It’s unlikely that the mystery will ever be solved.

‘His attention was distracted…’

Albert Hazen Wright (Class of 1904, M.A. 1905, Ph.D. 1908), a well-known herpetologist and zoologist, and his wife, Anna Allen Wright (Class of 1909), traveled extensively, particularly in the Okefenokee Swamp in the early 1920s, collecting live specimens. They wrote the classic guides to frogs and snakes.

The Cornell Daily Sun (Oct. 8, 1925) reported Wright had assembled a large collection of live reptiles, lizards and snakes from the Southwestern United States that he would display in McGraw Hall. The collection included diamondback rattlers, a green rattler, two ornate racers, a Gila monster, four chuck-a-wallas and iguanas. The snakes would be available to view for a few days then “converted into museum specimens.”

Days later, Cornell students read a Sun headline Oct. 17, 1925: “Professor Bitten by Bad-Tempered Rattler.” The Sun explained: “Dr. Wright was handling the snake, holding it by the neck, when his attention was distracted. The rattler took advantage of his relaxation of vigilance to plunge its poisonous fangs into Dr. Wright’s thumb.” Wright lived until 1970.

The botanical taxonomy of palms

One hundred years ago, with the world’s botanical taxonomy of palms in disarray, Liberty Hyde Bailey set out to correct that situation. The retired dean of Cornell’s College of Agriculture from 1910-49, Bailey visited the Caribbean and Mexico. He increased the known palm species from 700 in 1914 to several thousand by the late 1940s.

In Cuba, Bailey always called on noted botanist Brother Leon, a French-Canadian priest who taught at the Colegio de la Salle in Havana.

As Brother Leon and Bailey traveled through Cuba by train, both became thirsty in the tropical heat. “We stopped at the vendors. As usual, they were selling all sorts of things, including beer. [Brother Leon] lowered the window and bought two bottles,” Bailey recalled.

“I didn’t have any apparatus for getting the cap off the bottle of beer, so Brother Leon unbuttoned his robe and drew out a machete. He held the bottle up at arm’s length while standing in the aisle, and took a long-armed swipe with the machete and clipped the cap off as slick as a whistle,” wrote Bailey in a diary. “He had done that before!”

‘…into the nether regions…’

Sometimes the researchers became crestfallen. In his book “The Grail Bird,” Tim Gallagher describes a 1924 Florida expedition for Arthur (Class of 1907, M.A. 1908, Ph.D. 1911) and Elsa (Class of 1912, Ph.D. 1929) Allen, explaining how they found evidence of the ivory-billed woodpecker – a species that was in danger even then.

“… in the spring of 1924, the bird experienced the first in a series of miraculous resurrections. Arthur Allen and his wife, Elsa, who were traveling in Florida, checked out an alleged ivory-billed woodpecker sighting and managed to locate an active nest. Allen had no wish to collect the birds. ‘Since it is our belief that more is to be gained from the study of a living bird than from a series of museum specimens, we refrained from collecting the birds and planned our itinerary so as to spend the greater part of the following month studying them,’ [Arthur Allen] wrote.”

Gallagher continued: “To avoid placing undue stress on the birds, which for all he knew might be the last breeding pair on the planet, he didn’t set up camp next to them but stayed in town instead. The word was out, though. One day while he was away, a couple of local collectors shot the pair – legally. And so the ivory-billed woodpecker once more crossed into the nether regions between existence and extinction.”

In 1935, Allen and colleagues Peter Paul Kellogg (Class of 1929, Ph.D. 1938), graduate student James Tanner (Class of 1935, M.S. 1936, Ph.D. 1940) and artist George Miksch Sutton (Ph.D. 1932) organized the Cornell University-American Museum of Natural History expedition (sponsored by Albert R. Brand, Class of 1929) to Louisiana where they produced the first sound recordings and motion pictures of a nest of ivory-billed woodpeckers.

Out-of-this-world expeditions

Very far above Cayuga’s waters, Cornell boasts of eight alumni who have traveled in space, and their out-of-this-world expeditions have included six-month stays, long space walks, medical experiments and space-station docking.

Ellen Baker, M.D. ’78, became the first Cornellian in space aboard Atlantis in October 1989; the crew deployed the Galileo spacecraft to explore Jupiter. Baker later joined the Columbia (June 1992) and Atlantis (June 1995) space shuttle crews for a total of 11.6 million miles flown in space.

The late David Low ’80 flew aboard Columbia (January 1990), Atlantis (August 1991) and aboard Endeavour (June 1993), where he conducted a six-hour space walk, the first Cornellian space walker. Other Cornellians in space were astronauts Daniel Barry ’75; Jay Buckley ’81; Martin Fettman ’76, M.S./D.V.M. ’80; Mae Jemison, M.D. ’81; Ed Lu ’84; and Donald Thomas ’80.

For undergraduates in the new millennium, exploring Mars was a ground-based mission. During the landing of the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity, undergraduate students conducted mission work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The students received valuable scientific experience working on Mars rover teams, scientifically led by Cornell astronomy professors Steve Squyres ’78, Ph.D. ’81 and Jim Bell. They included Stephanie Gil ‘06; Chase Million ‘07, Dmitry Savransky ’04, M.Eng. ’05; and Alex Hayes ’03, M.Eng. ’03 – who have become physicists, engineers and planetary scientists.

The expedition experience follows. For example, Savransky has joined Cornell’s engineering faculty as an assistant professor, and Hayes, an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell, explores the surface of Titan – one of Saturn’s moons. Million founded Million Concepts, a software engineering firm for research scientists. Gil is a doctoral candidate at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe