Threatened plants have rosier future with BTI technique

By Patricia Waldron

Woodland agrimony isn’t much to look at – the short plant with jagged leaves and tiny yellow flowers is likely to be overlooked on an afternoon hike – but this rare, threatened plant got a high-tech hand from researchers at the Cornell-affiliated Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI).

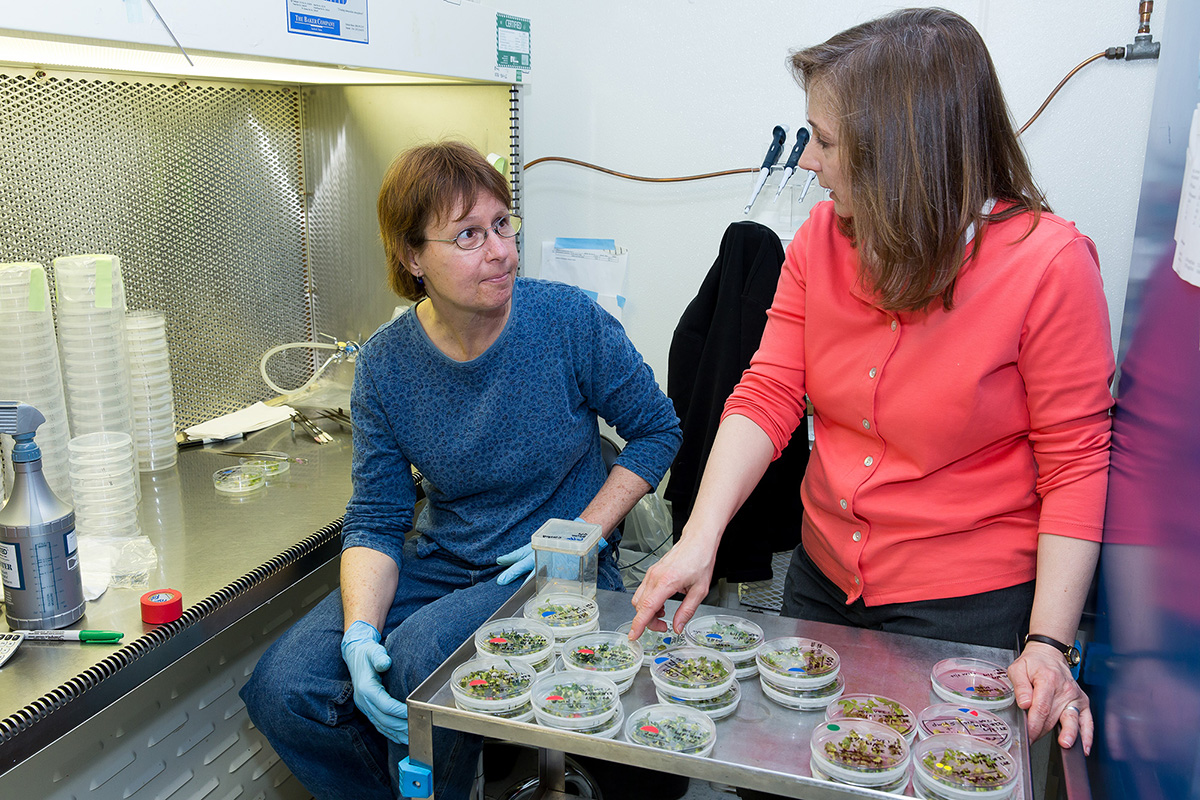

BTI scientist Joyce Van Eck and research assistant Patricia Keen developed a test tube tissue culture procedure that multiplied the plant’s numbers, which they detailed in Native Plants Journal. They collaborated with Victoria Nuzzo, ecologist and founder of Natural Area Consultants, who transferred the lab-cultured plants to forests in New York state as part of a study to learn why the species is in decline.

Nuzzo and her colleagues Bernd Blossey, associate professor in Cornell’s Department of Natural Resources, and Andrea Dávalos, a research associate in his lab, reached out to Van Eck to see if she could help them with a research quandary.

“We were looking at the impacts of different stressors on four rare native plants in the northern U.S. and needed seeds and seedlings of each species for our experiments,” said Nuzzo. “One of the rare plants we worked with was woodland agrimony. We found a single population, and we simply couldn’t collect enough seeds to use in our experiments or to grow seedlings to transplant.”

Van Eck and Keen began developing a procedure to propagate the plant, starting with common agrimony and then switching to the threatened woodland agrimony once they had worked out the details.

The first – and most troublesome – step was removing bacteria and fungal contamination from the plant segments used to start the in vitro multiplication process.

“We really struggled trying to get material that was clean for tissue culture. We tried all sorts of things,” said Van Eck. “There’s a fine line sometimes between getting rid of the contaminants and the plant,” she laughed.

Ultimately, Keen overcame the contamination issue through a strenuous washing protocol. She split the shoots every four weeks to make new plantlets, which grew “true-to-type,” just like the original. After a stay in the greenhouse to harden, the woodland agrimony was ready for planting.

In six months, Keen had generated 1,013 plants from a starting population of just 35.

“I think the tissue culture option is something people in the conservation field should consider, if they aren’t already,” said Van Eck. “When you have limited plant material and need a way to bulk up the numbers, tissue culture is a great way to do that.”

Nuzzo and her colleagues planted the agrimony at 12 field sites where they could observe and control the effects of slugs, deer, earthworms, invasive plants and other environmental factors. Though interactions between different stressors are complex, grazing deer appear to be an important factor contributing to the decline of the remaining woodland agrimony populations.

Currently, there are no wide-scale agrimony replanting efforts planned, but the study shows that replenishing the population through tissue culture is a viable option.

While Van Eck and Keen’s role in the project is over, their test tube plants live on. In many of the locations, the woodland agrimony is reproducing the old-fashioned way and establishing new populations.

Patricia Waldron is the staff science writer for the Boyce Thompson Institute.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe