Wiesner team images tiny quasicrystals as they form

By Tom Fleischman

When Israeli scientist Daniel Shechtman first saw a quasicrystal through his microscope in 1982, he reportedly thought to himself, “Eyn chaya kazo” – Hebrew for, “There can be no such creature.”

But there is, and the quasicrystal has become a subject of much research in the 35 years since Shechtman’s Nobel Prize-winning discovery. What makes quasicrystals so interesting? Their unusual structure: Atoms in quasicrystals are arranged in an orderly but nonperiodic way, unlike most crystals, which are made up of a three-dimensional, orderly and periodic (repeating) arrangement of atoms.

The lab of Uli Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Engineering in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE), has joined scientists pursuing this relatively new area of study. And much like Shechtman, who discovered quasicrystals while studying diffraction patterns of aluminum-manganese crystals, Wiesner came upon quasicrystals a bit by accident.

While working with silica nanoparticles – from which the Wiesner lab’s patented Cornell dots (or C dots) are made – one of his students stumbled upon an unusual non-periodic but ordered silica structure, directed by chemically induced self-assembly of groups of molecules, or micelles.

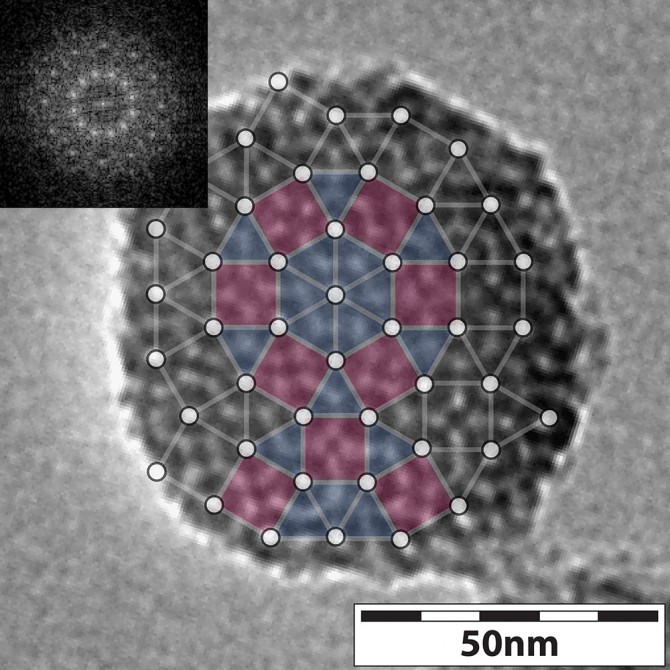

“For the first time, we see this [quasicrystal] structure in nanoparticles, which had never been seen before to the best of our knowledge,” said Wiesner, whose research team proceeded to conduct hundreds of experiments to capture the formation of these structures at early stages of their development.

Their work resulted in a paper, “Formation Pathways of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles With Dodecagonal Tiling,” published Aug. 15 in Nature Communications. Lead authors are former MSE doctoral student Yao Sun, current postdoc Kai Ma and doctoral student Teresa Kao. Other contributors included Lena Kourkoutis, assistant professor of applied and engineering physics; Veit Elser, professor of physics; and graduate students Katherine Spoth, Hiroaki Sai and Duhan Zhang.

To study the evolution of silica nanoparticle quasicrystals, the best solution would be to take video of the growth process, but that was not possible, Wiesner said.

“The structures are so small, you can only see them through an electron microscope,” he said. “Silica degrades under the electron beam, so to look at one particle over a longer period of time is not possible.”

The solution? Conduct many experiments, stopping the growth process of the quasicrystals at varying points, imaging with transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and comparing results with computer simulations, conducted by Kao. This imaging, done by Sun and Ma, gave the team a sort of time-lapse look at the quasicrystal growth process, which they could control in a couple of different ways.

One way was to vary the concentration of the chemical compound mesitylene, also known as TMB, a pore expander. The imaging, including cryo-TEM performed by Spoth, showed that as TMB concentration increased, micelles became bigger and more heterogeneous. Adding TMB induced four mesoporous nanoparticle structure changes, starting as a hexagonal and winding up as a dodecagonal (12-sided) quasicrystal.

“The more TMB we add, the broader the pore size distribution,” Wiesner said, “and that perturbs the crystal formation and leads to the quasicrystals.”

The other way to make these structures evolve is mechanical. Starting with a hexagonal crystal structure, the team found that by simply stirring the solution more and more vigorously, they introduced a disturbance that also changed the micelle size distribution and triggered the same structural changes “all the way to the quasicrystal,” Wiesner said.

A lot of the discovery in this work was “serendipity,” Wiesner said, the result of “hundreds and hundreds” of growth experiments conducted by the students.

The more insight gained into the early formation of these unique particles, the better his understanding of silica nanoparticles, which are at the heart of his group’s work with Cornell dots.

“As the techniques become better, the ability to see small structures and better understand their assembly mechanisms is improving,” he said. “And whatever helps us understand these early formation steps will help us to design better materials in the end.”

The work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, the National Science Foundation and the Cornell Center for Materials Research, and made use of the Nanobiotechnology Center at Cornell. Additional support came from the Weill Institute and the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe