Atmospheric winds carry nutrients from Africa to Amazon

By Blaine Friedlander

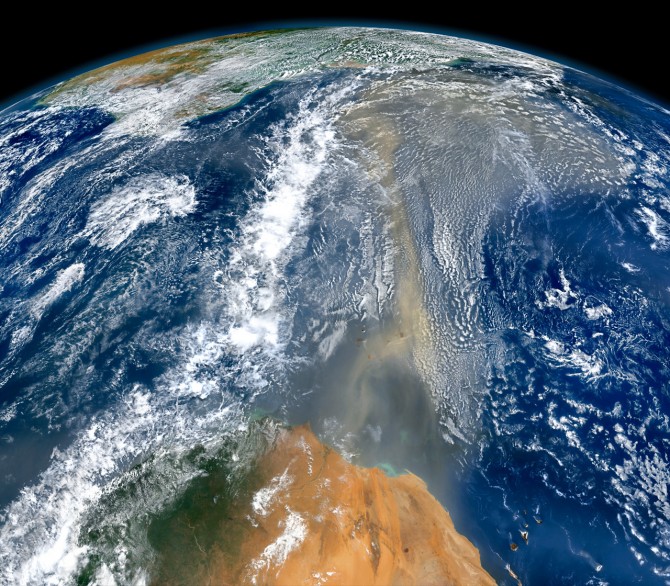

Buoyed by an atmospheric “superhighway,” smoke from lightning-sparked African savanna and forest fires deposit unexpectedly large amounts of nutrient-rich phosphorus in a river basin an ocean away.

“It’s so counterintuitive that the air would deposit this amount of nutrition for the land,” said Natalie Mahowald, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, discussing new research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, July 24.

Douglas Hamilton, a Cornell postdoctoral researcher, joined Mahowald on preparing analytical models for the work, “African Biomass Burning Is a Substantial Source of Phosphorus Deposition to the Amazon, Tropical Atlantic Ocean and Southern Ocean.” Doctoral student Anne E. Barkley, and professors Joseph M. Prospero and Cassandra J. Gaston – all from the University of Miami – led the research.

Plumes of heavy smoke from grassy, shrubby natural wildfires throughout the African savannas climb into the tropical easterly Saharan air layer and cross the Atlantic Ocean. The smoke has small amounts of phosphorus, which fertilizes the Amazon forest thousands of miles away.

During the spring and summer, phosphorus in dust from Africa dominates the flow in the Northern Hemisphere. But in the fall and winter, fire smoke gets swept up into the stream; fine particles from the smoke (aerosols) fall via raindrops and gravitational settling into the tropical portion of the Atlantic Ocean – and throughout the Amazon basin.

“Rapid-burning, natural savanna fires are a major contributor to nourishing phosphorus,” said Hamilton, who noted that human-caused fire was a minor factor.

Mahowald, a faculty fellow at Cornell’s Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, said phosphorus in the soil in the Amazon is limited. There is so much biological activity in the Amazon that it gets easily consumed in the rainforest area.

“This new phosphorus is fertilizing the Amazon,” she said.

Climate change is expected to influence African dust and smoke transport due to factors that include land-use modification, wind intensity and sources of biomass burning, according to the researchers. In the Sahel region – the transition zone between the Sahara and sub-Saharan Africa – land has been changing from a frequently burned savanna to agricultural land, prompting wildfire suppression. Mahowald said this could impact phosphorus deposition in the Amazon and the waters near South America.

Support for Mahowald and Hamilton on this paper came from the U.S. Department of Energy and the Atkinson Center.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe