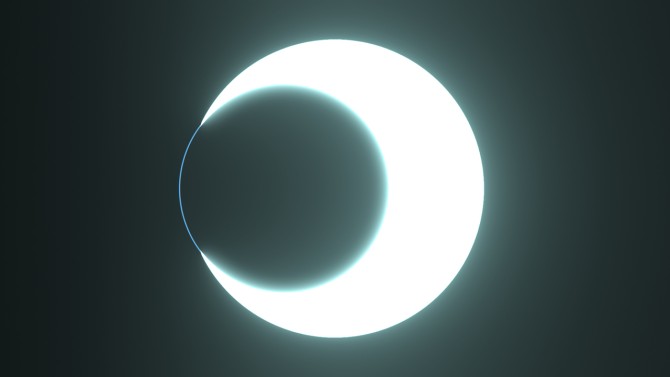

A rocky planet orbiting a white dwarf – a star in a phase after death – would present an excellent opportunity to search for molecules that signify life using the James Webb Space Telescope, say Lisa Kaltenegger, director of Cornell University’s Carl Sagan Institute, and Ryan MacDonald, a research associate.

Can life survive a star’s death? Webb telescope will explore

By Kate Blackwood

When stars like our sun die, all that remains is an exposed core – a white dwarf. A planet orbiting a white dwarf presents a promising opportunity to determine if life can survive the death of its star, according to Cornell researchers.

In a study published Sept. 16 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, they show how NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope could find signatures of life on Earth-like planets orbiting white dwarfs.

A planet orbiting a small star produces strong atmospheric signals when it passes in front, or “transits,” its host star. White dwarfs push this to the extreme: They are 100 times smaller than our sun, almost as small as Earth, affording astronomers a rare opportunity to characterize rocky planets.

“If rocky planets exist around white dwarfs, we could spot signs of life on them in the next few years,” said corresponding author Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences and director of the Carl Sagan Institute.

Co-lead author Ryan MacDonald, a research associate at the institute, said the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in October 2021, is uniquely placed to find signatures of life on rocky exoplanets.

“When observing Earth-like planets orbiting white dwarfs, the James Webb Space Telescope can detect water and carbon dioxide within a matter of hours,” MacDonald said. “Two days of observing time with this powerful telescope would allow the discovery of biosignature gases, such as ozone and methane.”

The discovery of the first transiting giant planet orbiting a white dwarf (WD 1856+534b), announced Sept. 16 in a separate paper – led by co-author Andrew Vanderburg, assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison – proves the existence of planets around white dwarfs. Kaltenegger is a co-author on this paper, as well.

This planet is a gas giant and therefore not able to sustain life. But its existence suggests that smaller rocky planets, which could sustain life, could also exist in the habitable zones of white dwarfs.

“We know now that giant planets can exist around white dwarfs, and evidence stretches back over 100 years showing rocky material polluting light from white dwarfs. There are certainly small rocks in white dwarf systems,” MacDonald said. “It’s a logical leap to imagine a rocky planet like the Earth orbiting a white dwarf.”

The researchers combined state-of-the-art analysis techniques routinely used to detect gases in giant exoplanet atmospheres with the Hubble Space Telescope with model atmospheres of white dwarf planets from previous Cornell research.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite is now looking for such rocky planets around white dwarfs. If and when one of these worlds is found, Kaltenegger and her team have developed the models and tools to identify signs of life in the planet’s atmosphere. The Webb telescope could soon begin this search.

The implications of finding signatures of life on a planet orbiting a white dwarf are profound, Kaltenegger said. Most stars, including our sun, will one day end up as white dwarfs.

“What if the death of the star is not the end for life?” she said. “Could life go on, even once our sun has died? Signs of life on planets orbiting white dwarfs would not only show the incredible tenacity of life, but perhaps also a glimpse into our future.”

Other contributors to this research are Thea Kozakis, Ph.D. ’20, and Nikole Lewis, assistant professor of astronomy and deputy director of the Carl Sagan Institute.

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe