‘Emancipation’s Daughters’ celebrates five iconic Black women

By Kate Blackwood

In 2000, Riché Richardson, along with people across the United States, were struck by Condoleezza Rice’s speech at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia – and by the subsequent impact Rice made around the world as secretary of state in the administration of former President George W. Bush.

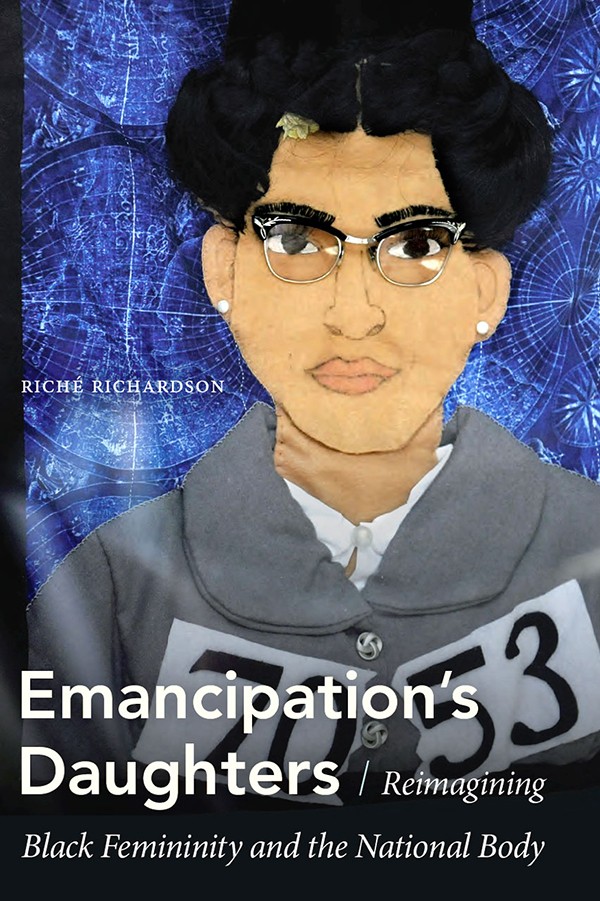

“Rice stood out for me, as she did for a lot of other Black women, because of the key role she played. Her symbolic power was undeniable,” Richardson, associate professor in the Africana Studies and Research Center, wrote in her new book, “Emancipation’s Daughters: Reimagining Black Femininity and the National Body.”

Rice’s prominent leadership position was made possible by a long line of predecessors who had “paved the way and established salient voices in politics in an effort to achieve a more democratic America for Black people and all others who have been excluded from its opportunities,” Richardson wrote.

In “Emancipation’s Daughters,” Richardson examines five iconic Black women leaders – Mary McLeod Bethune, Rosa Parks, Condoleezza Rice, Michelle Obama and Beyoncé – who have contested racial stereotypes and constructed new national narratives of Black womanhood in the United States. These leaders, she writes, have defied racist images of Black women and rewritten scripts of femininity designed to exclude Black women from civic participation.

“They remind us of the concrete contributions that Black women have made in the political realm, becoming iconic and coming to voice,” Richardson said. She said she made some hard choices to focus the book’s chapters on just five women; the text includes significant mention of many more.

Through these examples, Richardson examines what happens when Black women are able to gain voice and legibility at the national level and assert their subjectivity, “to the point that they challenge conventional stereotypes of Black women like Aunt Jemima, while expanding definitions of womanhood, motherhood and American identity,” she wrote.

In this book and in her public writing, Richardson critiques Aunt Jemima, a figure used by the Quaker Oats Company (owned by PepsiCo) since the 1920s to advertise pancake mix and syrup, as a negative image of Black womanhood. “Can We Please, Finally, Get Rid of ‘Aunt Jemima’?” she first argued in the New York Times in 2015.

“The Aunt Jemima stereotype is just one of the earliest illustrations of how the mammy figure established foundations for recurring citations of pathological images of the Black maternal body throughout the twentieth century,” Richardson wrote. “These images have been central in mediating public dialogues about Black women, to the point of affecting political policymaking.”

In “Emancipation’s Daughters,” Richardson highlights the ways in which Black women leaders have consistently evoked Black families to present Black people as being representative Americans – and part of the American family, she wrote.

“Such alternative scripts of the Black mother unsettle the mammy myth,” Richardson wrote.

In the first chapter, Richardson writes about educator, activist and humanitarian Mary McLeod Bethune, a key model in the nations’ public sphere who organized a national and global Black agenda during the Great Depression, laying a foundation for important civil rights work to come.

Richardson then examines the legacy of Rosa Parks, “who emerged as a model of national femininity when her choice to remain seated on a bus in Montgomery played a central role in the crystallization of the civil rights movement,” Richardson wrote.

Richardson returns to Condoleezza Rice in the third chapter, examining how Rice invoked her family as a representative American family and related chapters of American civil rights struggles into foreign policy, including the war on terror.

In the fourth chapter, Richardson focuses on Michelle Obama – her family background, her key role in the 2008 Democratic National Convention, and her self-fashioning as “Mom-in-Chief,” which framed her as a national mother figure.

Concluding the book, Richardson writes about Beyoncé, who serenaded Michelle and Barack Obama during their first dance as president and first lady in 2009, becoming “further enshrined in the national arena as an icon.”

“Through her national and global iconicity and increasing political visibility and influence, Beyoncé illustrates the role of popular culture in shaping national femininity,” Richardson wrote.

Richardson’s first book, “Black Masculinity and the U.S. South: From Uncle Tom to Gansta,” focused on the role of the U.S. South in nationalizing ideologies of Black masculinity. “Emancipation’s Daughters” builds on the first book, Richardson wrote, by looking at the role of the region in nationalizing models of Black femininity.

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe