James Turner, the founding director of Cornell’s Africana Studies and Research Center and a a professor emeritus of African and African American Politics and Social Policy in the College of Arts and Sciences, died Aug. 6 in Ithaca.

James Turner, a ‘giant’ of Africana studies, dies at 82

By David Nutt, Cornell Chronicle

James Turner, the founding director of Cornell’s Africana Studies and Research Center and a pioneer of the multidisciplinary approach to exploring the African diaspora, died Aug. 6 in Ithaca. He was 82.

Turner, a professor emeritus of African and African American Politics and Social Policy in the College of Arts and Sciences, shaped generations of Black scholars and other diverse students over the last 50 years.

His early stewardship of the center, during an era of enormous civil turmoil, put Cornell at the forefront of Africana studies and provided a template for understanding and articulating Black experience that is now replicated in institutions throughout the world.

“Professor Turner is a giant who has transitioned to the world of the Ancestors, but he has not moved on,” said N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba, professor of Africana studies and director of the Institute for African Development. “He’s very much here, because of the impact, because of the foresight, because of the intellectual, theoretical, philosophical articulation of what Africana means and what has become an institution. He has done that. And much more.”

One of eight children, Turner was born in Brooklyn in 1940 and raised in public housing in lower Manhattan. His father was a laborer, and Turner grew up with the expectation that he would join the garment trade. He attended the High School of Fashion Industries and upon graduating in 1957, he got a job at Ripley’s Clothing Store.

In his free time, however, he was venturing out to experience the city’s jazz scene, and he soon began delving into the rich culture of Harlem. It was there he found a mentor in Pan-Africanist historian John Henrik Clarke, and a lifelong inspiration in Clarke’s close friend, the minister and civil rights leader Malcolm X. Turner often saw Malcolm X speaking on the corner of 125th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, and the experience made a lasting impression on Turner, whose own research on Malcolm X’s political philosophy would later inform the acclaimed PBS series “Eyes on the Prize.”

“Malcolm was a master teacher,” Turner once said. “You couldn’t listen to him and not come away with something. It was more than charisma, it was the way he was able to use the language of our people and make (them) understand.”

Turner left the garment business for social work, first with the Mobilization for Youth program at Columbia University’s School of Social Work in 1961, for which he coded data on the involvement of New York youth in gangs. He also worked with the New York Youth Board to counsel gang members and resolve gang conflicts.

Looking to pursue a career in academia, Turner and his wife, Janice Turner, moved to Michigan, where Turner earned a bachelor’s degree from Central Michigan University. He eventually earned a master’s degree in African studies from Northwestern University, a certificate in African Studies from Northwestern’s African Studies Center and a Ph.D. from Union Graduate School in Cincinnati.

Meeting the needs of Black students

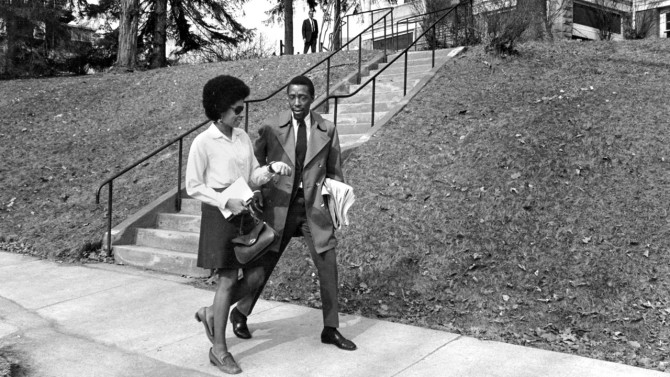

As a 26-year old Northwestern University graduate student, Turner led more than 100 Black students to conduct a two-day sit-in at the university bursar’s office to protest discrimination and improve campus conditions – an action that led to the creation of Northwestern’s African American studies department.

Turner was gaining as much attention for his academic ideas as his activism. Cornell’s Afro-American Society was so impressed by a presentation he delivered at a conference at Howard University that he became the top pick to lead a newly proposed Black studies center.

In June 1969, Turner accepted the position, saying the program had the potential to be “one of the most far-reaching, imaginative and creative programs in the country.”

As Turner later recounted, he arrived at a university that had few tenured Black professors and no courses in African-American history or culture.

The Africana Center, located at 320 Wait Ave., opened its doors in September 1969 with 160 students, 10 courses and seven faculty members, including Gloria Joseph, Ph.D. ’67. Only seven months later, on April 1, 1970, the building was destroyed in a suspected arson attack.

A new home for the center was established at 310 Triphammer Road, and a plaque commemorating the original site was unveiled in 2016.

A flagship for Black studies

The Africana Center quickly emerged as a flagship for Black studies at a time when many universities were only giving lip service to the notion of Black scholarship, when they weren’t dismissing it outright as a fad, according to Robert L. Harris Jr., emeritus professor of Africana studies, who joined the center in 1976 and served as its director from 1986 to 1991 and 2010 to 2012.

The center succeeded in establishing the very substance of Africana studies, he said.

“The program that James Turner had established, the faculty that he had recruited – there was a seriousness to the Africana Center,” Harris said. “And of course, over time, we proved the critics wrong.”

The center had been originally slated to be called the Center for Afro-American Studies, but Turner’s vision extended far beyond that, Harris said.

While the term “Africana” had been used by leading Black intellectuals, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, the term had not taken hold in academia until Turner used it to frame the global experience of all who were part of the African diaspora, despite their geography, according to Assié-Lumumba.

“In Africana studies, you cannot dissect it and say, well, here is a little piece of history, here is another section of the literature, here is the sociological part of your contribution, here is the psychological, here is the political – no,” Assié-Lumumba said. “You hear now about interdisciplinarity; well, Africana studies, with Professor Turner’s conceptualization, was the precursor.”

She described Turner as an attentive and compassionate colleague who sometimes called her “professor,” sometimes “sister,” and always welcomed her into his office. Even if he was already packing up to go home for the day, he would invite her to sit down and would listen to her with great focus.

That compassion was not limited to faculty and students.

“He was committed to justice. He did not accept deliberate or incidental injustice to people,” Assié-Lumumba said.

Assié-Lumumba recalled once walking across North Campus with Turner when he pointed out a nearby construction crew.

“He said, ‘Look at the construction that is being done today. What is the diversity of the workforce? That’s not right.’ He was not only fighting for those who are coming to academia as students, as faculty, but he was fighting for everybody on the social ladder,” she said.

That fight included “the good battle to make Cornell a better place,” Assié-Lumumba said, and Turner’s work encompassed the aim of Ezra Cornell’s philosophy of “any person … any study” by granting everyone the equal opportunity – and the resources – to develop to their full potential.

“And give your very best,” she said. “Whatever you can contribute, make that contribution for the collective well-being and advancement and justice for everybody.”

An international presence

Turner served as the Africana Center’s director from 1969 to 1986 and returned for a five-year term from 1996 to 2001.

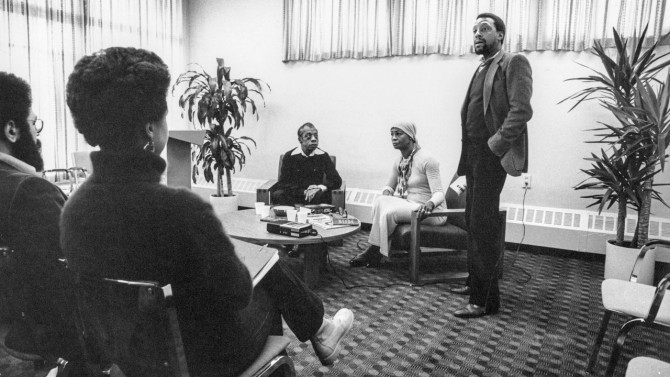

During his tenure, he created a robust intellectual environment at the center, bringing in speakers such as historian Vincent Harding, political scientist and activist Ronald Walters, poet and playwright Sonia Sanchez, and writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin. He also recruited a diverse array of scholars, including cultural psychologist William Cross and African American studies scholar Eleanor Trayler, a visiting scholar from Howard University.

“He did not have a litmus test for members of the faculty or for students,” Harris said. “He did look for a commitment, if you will, to the cause of people of African ancestry worldwide. But other than that, he was open to discussing different ideas. He let the students have their own wings. He had an influence on their thinking, but he wasn’t doctrinaire in his approach.”

As a political sociologist, Turner’s academic work explored systemic racism years before that concept became part of the popular lexicon.

“Many of us, and I have to say that I was proud to be one of them, we looked at the individual as being a racist,” Harris said. “We did not look at how the system itself produced those individuals. He was looking at this much earlier than many individuals were.”

Among his many honors, Turner received the Association of Black Sociologists’ Award of Distinction, and he served as president of the African Heritage Studies Association and on the editorial boards of several Black studies journals.

Under Turner’s leadership, the Africana Center became a means for connecting students to service learning projects and community development initiatives. Turner and his wife, Janice, a retired associate dean in the College of Arts and Sciences, were both deeply involved with the Ithaca community. Turner served on the board of directors at Southside Community Center and chaired the Tompkins County Human Rights Commission. He also worked with the Multicultural Resource Center as well as the Village at Ithaca, where his work inspired a collaborative effort with the Ithaca City School District known as the Equity Report Card.

“Professor Turner was an institution and bridge builder par excellence,” said Olufemi Taiwo, professor and chair of Africana studies. “But he was also an influential scholar and his leading role in not merely initiating but establishing the theoretical parameters of Africana studies anticipated many of the issues that continue to exercise scholars across the world even now. That his death is being mourned across the world is a testament to his generosity and an ecumenical spirit that is rare these days. We have lost a giant in all the resonances of that simple word.”

In 2010, the Cornell Black Alumni Association launched the James and Janice Turner Scholarship Endowment in honor of the Turners’ combined nine decades of service to Cornell.

Turner was also active on the international stage. He participated in the Anti -Apartheid movement in South Africa and served as national organizer of the Southern Africa Liberation Support Committee. In 1973, he co-chaired the International Congress of Africanists in Ethiopia, and in 1974, he served as chair of the North American delegation to the Sixth Pan African Congress. And Turner was a founding member of the African American lobbying organization TransAfrica.

In April 2019, the Africana Studies and Research Center held a two-day symposium honoring Turner and his legacy at Cornell.

Riché Richardson, professor of Africana studies, served as the chair of Africana’s Programming Committee, and said the public’s response to the symposium gave her “a very visceral understanding of the magnitude of Professor Turner’s legacy.”

Turner’s family, colleagues, many of his students and scholars traveled from across the country to participate in the celebration, which included nearly 40 talks. Audiences packed the rooms. Tributes poured in. The events went into overtime. Ithaca’s then-mayor Svante Myrick ’09 issued a proclamation designating the date as “Dr. James Turner Day in the City of Ithaca.”

“I remain deeply thankful that we had the opportunity to honor his intellectual and activist legacy in that moment,” Richardson said. “He was a brilliant intellectual, institution builder and thought leader. His hard work and sacrifices helped open the door and pave the way for newer generations of scholars. I will always treasure my memories of him, am blessed to have known him, and will always be thankful for his impact on my life and work.”

He is survived by Janice Turner and three children: Hassan, Sekai and Tshaka.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe