Ishion Hutchinson, the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor in the Humanities in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Book-length poem narrates struggle of young Black fighters in WWI

By Kate Blackwood

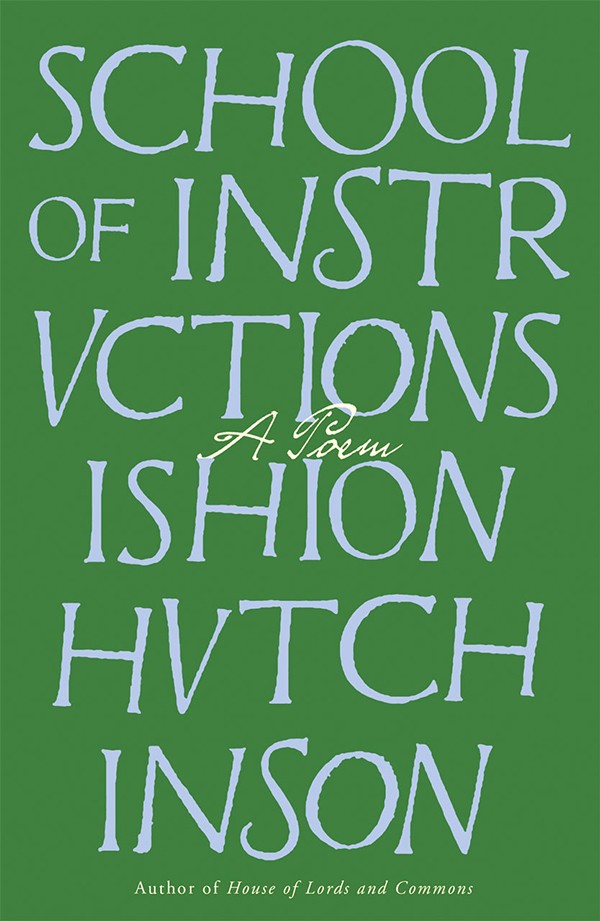

In the new book-length work, “School of Instructions: A Poem,” Ishion Hutchinson narrates the psychic and physical terrors of West Indian soldiers volunteering in British regiments in the Middle East during World War I. The book also follows the story of Godspeed, a schoolboy living in 1990s rural Jamaica.

The poem maps Godspeed’s daily experiences – at school, at home, outdoors – onto the travels and travails of the young Black soldiers as their battalion moves in and out of action, through locations found on ancient and current maps of the Middle East: Alexandria, Jordan Valley, Bethlehem and many others. They encounter violence, drudgery, loss, illness – but nevertheless share some characteristics, said Hutchinson, the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor in the Humanities in the College of Arts and Sciences, with the boy living decades later in a Jamaica free of British rule.

This work was commissioned by the British poet Karen McCarthy Woolf for the centenary of the First World War. It was short-listed for the 2023 T. S. Eliot Prize.

Hutchinson and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, associate professor of literatures in English, will give the Richard Cleaveland Memorial Reading on Feb. 15 in Hollis Auditorium in Goldwin Smith Hall.

The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with Hutchinson about the book:

Question: Would you share the story of this book’s beginning and your process in writing it?

Answer: The book’s beginning grew from my visits to the archives of the Imperial War Museum in London to look at material related to West Indian soldiers volunteering in British regiments during World War I. The commission was to write a single poem. However, what I found in the archives surprised and haunted me so much that the single poem grew, against my will, into a book which took about seven years to complete. It is hard, even in retrospect, to summarize or describe my process in writing the book. It amounts to constantly sublimating what I had found in the archives into a music of multiple registers that keep colliding into what I wrote.

Q: In telling the history of West Indian soldiers volunteering in British regiments, what can poetry bring to the material?

A: It is what the imagination brings to the material, and that is imploding the singularity of what is deemed to be the official, historical narrative. It is about finding the language to push against – as far as possible – the easy, formulaic expression of the material and in general whatever forces around us that flattens speech into an unimaginative babble. Poetry isn’t interested in “telling” us anything. Poetry moves us to recognize the deep shock of times – past, present, future – we inhabit at each moment.

Q: Who is Godspeed, and what role does he play in this work?

A: Godspeed is the name of a young boy whose story is intertwined with those of the West Indian soldiers. The poem isn’t from his point of view, but his experience is a tender counterpoint to the tragic reality of the soldiers.

Q: There’s a hand-drawn map, dated 1918, in the very front of the book. Where does it come from, and how does it preface the poem to come?

A: The map was drawn by T. E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia. It shows sections of battlefields in the Middle East and names areas where the West Indian soldiers fought. The sinuous squiggles and light shadings of the lines of the map have a beautiful, innocuous quality I like. They seem, at least to me, to hint at a kind of mischievous playfulness which is characteristic not just of Godspeed but also of some of the young soldiers encountered in the poem to come.

Kate Blackwood is a writer for the College of Arts & Sciences.

Media Contact

Abby Kozlowski

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe