Low-cost microbe can speed biological discovery

By Blaine Friedlander, Cornell Chronicle

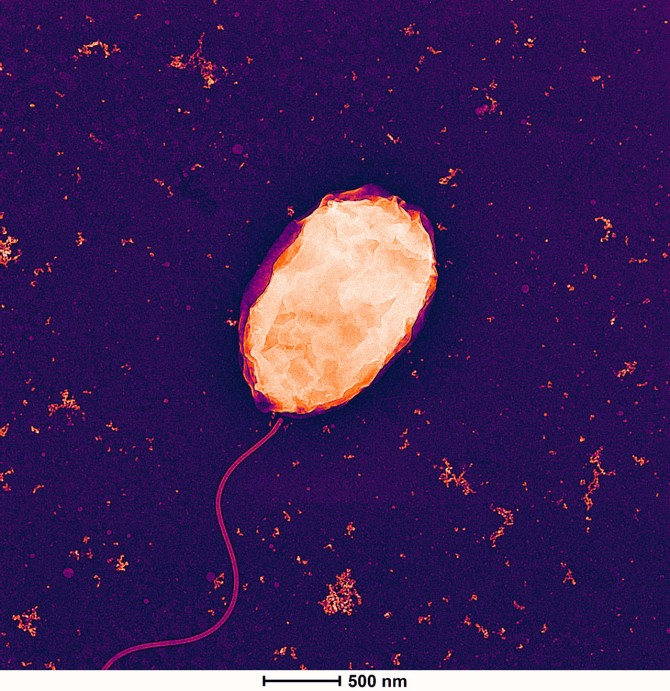

Cornell researchers have created a new version of a microbe to compete economically with E. coli – a bacteria commonly used as a research tool due to its ability to synthesize proteins – to conduct low-cost and scalable synthetic biological experiments.

As an inexpensive multiplier – much like having a photocopier in a test tube – the bacteria Vibrio natriegens could help labs test protein variants for creation of pharmaceuticals, synthetic fuels and sustainable compounds that battle weeds or pests. The microbe can work effectively without costly incubators, shakers or deep freezers and can be engineered within hours.

The research published Feb. 13 in PNAS Nexus.

“It’s really easy to produce,” said lead author David Specht, Ph.D. ’21, a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Buz Barstow, Ph.D. ’09, assistant professor of biological and environmental engineering in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

To study proteins for creating medical cures or fashioning fuels, researchers use a plasmid (a small piece of DNA) that acts as the instruction manual to make the molecular machine – a protein – of interest. Currently, when researchers place a plasmid into E. coli, they can create many copies to test several variants.

E. coli cells help molecular biologists multiply and manipulate plasmids for protein engineering, but the process is expensive since they often purchase the bacteria from manufacturers, must keep it cold and maintain rooms of expensive equipment to sustain it. A modified E. coli, used for this purpose, is also very fragile.

“As scientists, we don’t often know precisely what those regulatory or molecular sequences should be to achieve our goals,” said Barstow, a faculty fellow at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. “So we must test a lot of variants, and Vibrio natriegens allows researchers to scale up that process of testing.”

The microbe V. natriegens is not complicated, Specht said. “It’s so simple to make that someone with limited resources – like high school labs, home inventors or startup biological businesses – can do it,” he said.

Researcher Timothy Sheppard ’22, M.Eng. ’22, compared the simplicity of V. natriegens in conducting synthetic and molecular experiments to using a simple writing instrument hundreds of years old: “We’ve found nature’s pencil for cloning and conducting synthetic biology,” he said.

The process is inexpensive with V. natriegens, as it requires no capital equipment purchases and it can work at room temperature. The cells produced from V. natriegens grow quickly: According to the paper, a transformation started at 9 a.m. yields visible colonies by 5 p.m., each filled with masses of proteins.

“The microbe is a radically simple solution to a hard problem,” Barstow said.

In addition to Barstow, Specht and Sheppard, the co-authors of the research, “Efficient Natural Plasmid Transformation of Vibrio natriegens Enables Zero-capital Molecular Biology,” are Sijin Li, assistant professor in chemical and biomolecular engineering, Cornell Engineering; Greeshma Gadikota, associate professor in civil and environmental engineering (ENG); and Finn Kennedy ’25.

Funding for this research came from the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (U.S. Department of Energy); a Cornell 2030 Project Fast Grant; and a gift from Mary Fernando Conrad ’83 and Tony Conrad.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe