Once tadpoles lose lungs, they never get them back

By Krishna Ramanujan, Cornell Chronicle

Tadpole species that lost their lungs through evolution never re-evolve them, even when environmental change would make it advantageous – bucking long-standing assumptions about how lost traits can reemerge, according to a new study.

Typical tadpoles have three main ways to get oxygen: from the air, with lungs; from the water, through gills; and from the air through their skin.

Curiously, all frogs have lungs, so tadpoles retain the developmental genetics to regain lungs when environmental pressures might favor having them but instead evolve alternate solutions for acquiring oxygen from the air.

The study, published Oct. 27 in the journal Evolution, challenges long-standing assumptions that traits re-evolve more easily when the underlying developmental machinery of a lost trait remains intact.

“The study highlights both the predictability of evolution on the loss side and the utter unpredictability of the solutions that evolution finds for problems,” said Jackson Phillips, the study’s first author and a doctoral student in the lab of senior author, Molly Womack, assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (College of Arts and Sciences).

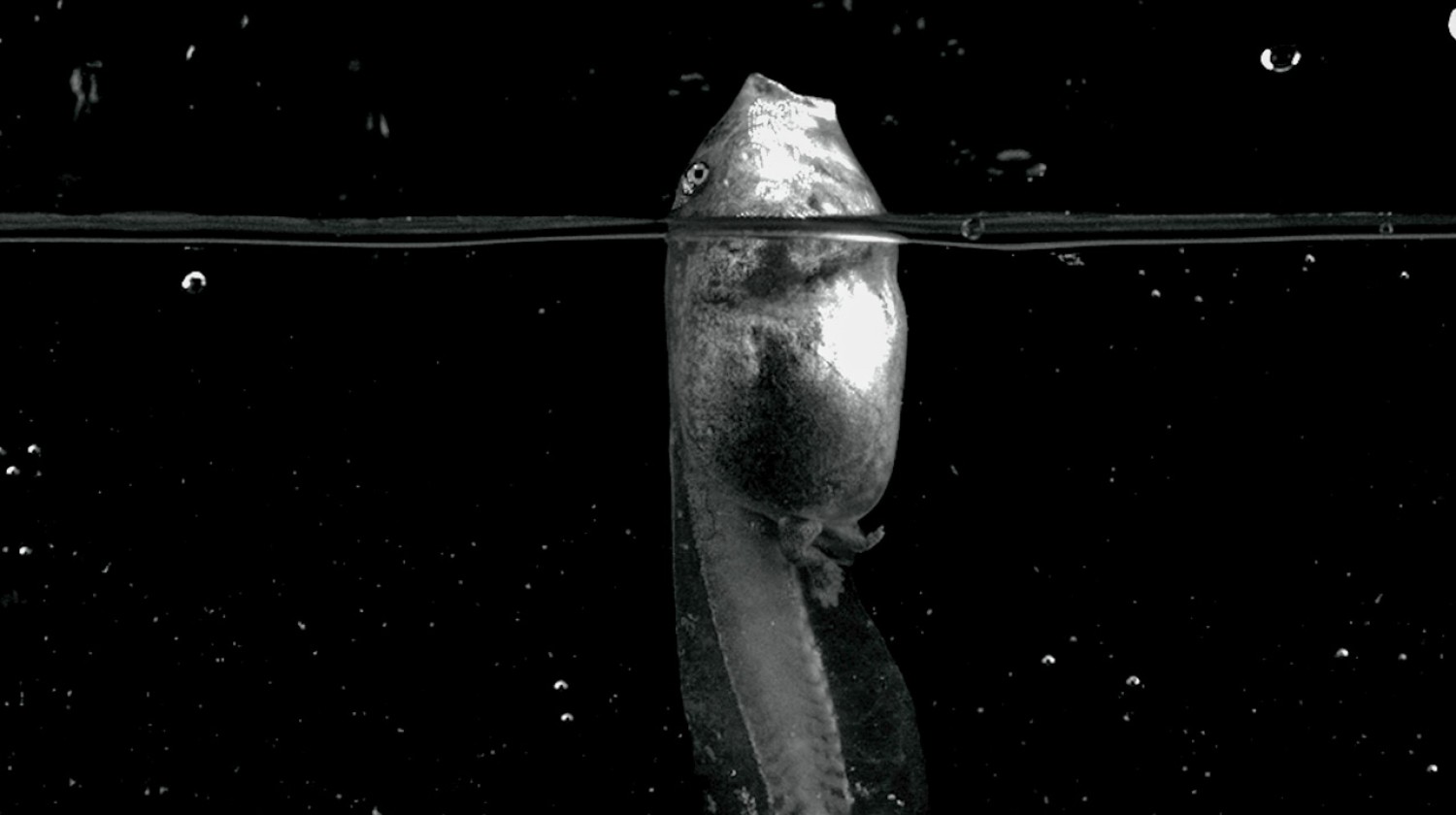

The northern torrent frog tadpole is lungless and endemic to the north of Borneo, where they live in fast-flowing clear streams and use their belly suckers to hold onto rocks in the flow.

The lungless African red toad, for example, lives in low oxygen waters, and while redeveloping lungs might seem like the obvious solution, these tadpoles have instead evolved a crest of vascularized skin on top of their heads. Phillips and Womack reported in a previous paper that most tadpoles use lungs to breathe air when they live in low oxygen environments, but African red toad tadpoles rise and press their crest out at the water’s surface, which acts as an external “head lung,” Phillips said.

Since tadpoles retain the genetic architecture to build lungs when they metamorphize into frogs, it’s easy to think they could activate that development two weeks earlier, while still tadpoles, when selection pressures require them to breathe air, Womack said.

“Even when tadpoles go into super hypoxic environments, with really low oxygen, we don’t ever see them get those lungs back,” Womack said. “Through this particular loss, we learn that evolution follows paths of least resistance, so even if you can, in theory, develop those lungs two weeks earlier, they also have other structures as tadpoles that bring oxygen in.”

For the study, the authors spent eight years gathering data by travelling to natural history museums around the world and dissecting specimens, when the museums had duplicates. Out of 530 species, including nearly every frog family and most genera, they identified 28 instances of lung loss. A total of over 5,000 species of frogs exist globally, 95 of which are known to be lungless as tadpoles.

Spadefoot tadpole breathes air to fill its lungs.

Though lungless tadpoles are found in ponds, streams and terrestrial habitats, most occupy either streams or terrestrial habitats.

The researchers relied on relationships among existing frog species that have been determined with genetics and computer models to trace back in time when lung losses would have occurred and estimate the ecological condition or habitats that those tadpoles might have lived in.

In general, within Phillips’ sample, a few patterns emerged relating to the environments where lungs were lost. For some stream tadpoles, losing their lungs might have been advantageous, since water in flowing streams is already highly oxygenated and lungs create buoyancy, so tadpoles with lungs may easily be carried downstream.

“If a tadpole is in a fast-flowing stream, it may not want a life raft in its body,” Womack said.

Stream tadpoles can occupy many different microhabitats. Phillips and colleagues found some tadpoles with sucker mouths, used to hold onto rocks in rapid water, were lungless. Another lungless group lives in sand, gravel or under leaf mats in streams. He also found, within the sample he collected, terrestrial tadpoles that lay eggs in nests on land, often near wet spray zones next to streams, also lost lungs. However, despite most currently existing frog species developing in ponds, it is likely tadpole lungs were only lost in past pond habitats a few times.

The researchers suspect that there might be something about air breathing that affects survival, such as floating downstream, danger of predation when coming to the surface or moving out from hideaways.

“Maybe the adaptation is due to selection against air breathing instead of selection against lungs,” Phillips said.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe