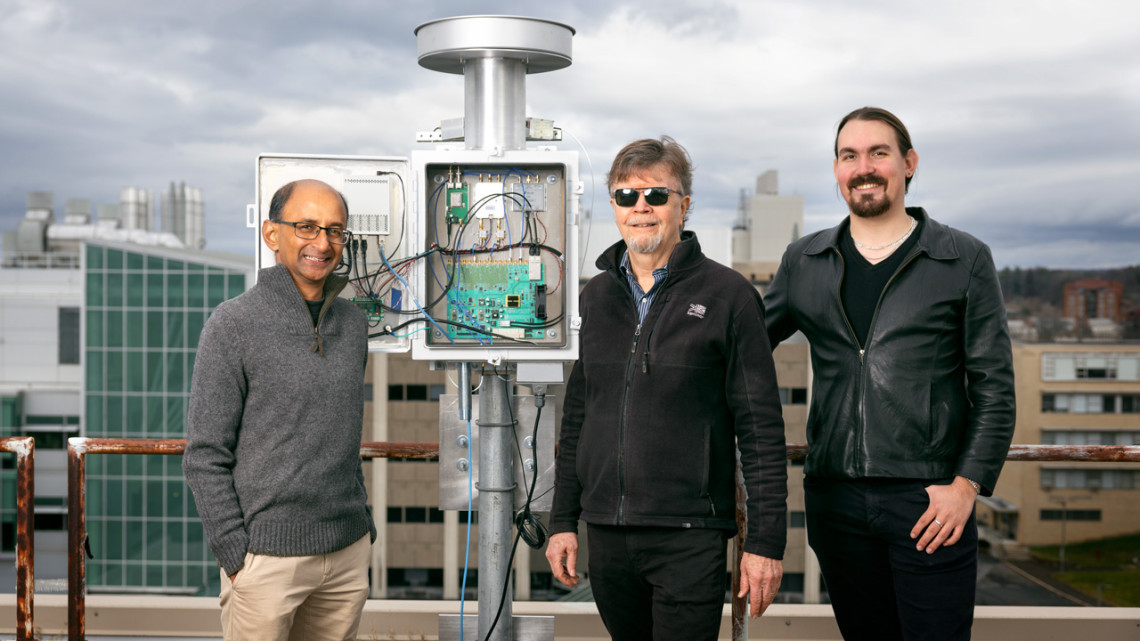

Shami Chatterjee, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences; James Cordes, the George Feldstein Professor of Astronomy; and doctoral student Sashabaw Niedbalski, on the roof of the Space Sciences Building next to the Global Radio Explorer Telescope.

Cake-pan telescope searches the sky for fast radio bursts

By Linda B. Glaser

When Cornell built the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico more than 60 years ago, it was the world’s largest. Now, Cornell has built one of the world’s smallest – out of cake pans.

“It works and it’s cost-effective,” said Sashabaw Niedbalski, a fifth-year doctoral candidate in astronomy.

The Global Radio Explorer (GReX) telescope is a series of eight terminals being built and tested at Cornell and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and installed at locations around the world. Cornell’s terminal is on the roof of the Space Sciences Building.

Their goal: to find the brightest of the numerous fast radio bursts (FRBs) that occur each day, and which last only milliseconds.

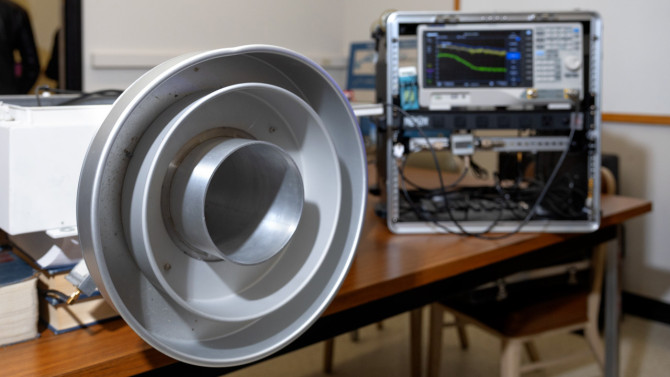

Why cake pans? It’s their geometry: Concentric cake pans form a horn-style feed antenna that reduces the sensitivity to human-made signals coming from the horizon and enables the telescope to focus its attention straight up through the atmosphere, where there are fewer human-made devices emitting radio waves.

“Every day there are on the order of 10,000 of these bursts going off all over the sky. It’s like flash bulbs popping off. But they’re millisecond bursts, and unless you’re looking at that patch of the sky at that specific millisecond, you’re never going to see it,” said team member Shami Chatterjee, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). “At any given time, we don’t have eyes on the radio sky like we do at optical wavelengths – which is why fast radio bursts are such a recent discovery.”

The goal of GReX is to fill this gap. Since each station can see 10% to 20% of the total sky, once all telescopes are deployed, researchers will have an instantaneous field of view over a large fraction of the sky. The eventual goal with a potential deployment of a second wave of terminals is to monitor all of the sky, all of the time.

“There are no other radio telescope projects that I’m aware of doing that,” Niedbalski said.

Bursts detected by GReX – previously known as Galactic Radio Explorer – are likely to originate from some nearby galaxies as well as from the Milky Way, and will be useful for probing local interstellar and intergalactic media. The data gathered could provide clues into the environments of the bursts’ sources and how they were formed, said team member James Cordes, the George Feldstein Professor of Astronomy (A&S).

GReX builds on a previous project at Caltech, STARE2, that caught an extraordinarily bright burst from a magnetar in the Milky Way (around a million times brighter than similar bursts from other galactic sources), providing proof-of-concept for the GReX design.

“We took the things that worked well there, built on them, and turned it from a single type of station that’s located within the southwestern U.S. into an international project,” Niedbalski said.

The multilocation detectors in the GReX network have another advantage: Because they don’t have the same local environment, a detection caused by human-made sources, or natural ones like a lightning storm, will be seen only on one detector and not on others. Multiple detectors also make it possible to triangulate the directional source of the signal.

In addition to at Cornell, instruments are currently installed and running at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory and the Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California; Harvard; and Ireland’s Birr Observatory. A sixth is in Australia and is expected to be operational soon. Once the final two have been tested, they’ll be shipped to new sites, potentially in Chile and another site in the northeastern U.S., Niedbalski said.

GReX data pours in at 8 gigabytes per second, Niedbalski said. It would be impossible to save this volume of data for later analysis, he said, so the team employs sophisticated digital backend electronics while feeding the data into a 60-second buffer. The system has 60 seconds to analyze the data and determine if it holds anything potentially significant before it is overridden by new data. If it finds something, that data is saved to disk for later examination by the scientists.

The telescope software is designed in a modular structure, similar to Lego blocks, making it possible to upgrade or replace one part of the system without having to adjust the rest. The Cornell team continues to refine the system and work on updates.

Though GReX was conceived to discover radio bursts from known classes of objects, Cordes said, it is conceivable that GReX will discover bursts from other kinds of stars or from exotic objects like cosmic strings.

“We astronomers tend to like this kind of ‘discovery space’ argument,” Cordes said, “that when looking at the sky in a somewhat new way – a wide field of view, in the GReX case – we tend to find new things.”

Linda B. Glaser is news and media relations manager for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe