Drug lifts barrier for immunotherapy to fight rare liver cancer

By Krishna Ramanujan, Cornell Chronicle

Immunotherapy – which activates the body’s own immune system to kill cancer cells – has not worked well against a rare and fatal liver cancer, but a new study finds an existing FDA-approved drug may allow the immunotherapy to fight the cancer as intended, opening the door to a potential treatment.

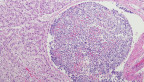

Fibrolamellar carcinoma primarily affects children and young adults and accounts for up to 2% of all liver cancers. It currently has no cure and has often metastasized by the time it is detected, leaving patients with a short life expectancy.

The study, published Feb. 17 in the journal Gastroenterology, describes how fibrolamellar tumors rewire their local microenvironments such that the body’s immune T cells become sequestered away from the cancer cells where they can’t fight the disease – a process called T-cell exclusion. They also found that AMD3100, a drug currently used to treat a different disorder, can prevent the tumors from sequestering T cells, freeing them to attack the cancer.

“Our results provide among the first indications of why a type of immunotherapy called immune checkpoint inhibition hasn’t worked well in these patients, and even if this particular drug isn’t the end-all-be-all, it teaches us that this T-cell exclusion phenomenon is an important one to tackle in fibrolamellar carcinoma,” said Praveen Sethupathy ‘03, professor of physiological genomics and chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences in the College of Veterinary Medicine. Sethupathy is the paper’s co-senior author, along with Dr. Venu Pillarisetty, a surgical oncologist at the University of Washington.

In the study, the researchers took advantage of single-nucleus transcriptomics, a cutting-edge technology that allowed them to separate each individual cell’s nucleus from a mass of tissue and determine what genes are turned on in each.

“It wasn’t until we were able to use this technology that the picture of the tumor microenvironment began to clear up for us,” said Andreas Stephanou, a co-first author on the study and a Cornell graduate student co-mentored by Sethupathy and Iwijn de Vlaminck, associate professor in the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering in the Duffield College of Engineering.

Normally, when clinicians administer immune checkpoint inhibitors, they activate the body’s own immune T cells to migrate to the core of the cancer to try and kill the tumor cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors can be highly effective against liver, lung, kidney and bladder cancers, as well as melanoma, but many cancers – pancreatic, prostate, brain – can be resistant. The tumor microenvironment and T-cell sequestration provide clues to why some cancers don’t respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Fibrolamellar carcinoma is named for the thick fibrous bands that run through the tumors. “Despite all of the recent advances in the study of this cancer, we still haven’t pinpointed how these fibrous bands contribute, if at all, to the tumor’s progression,” Stephanou said. The bands are created by a population of cells called stellate cells, which are normal cells in the liver that get modified by the cancer. When altered, these stellate cells release fibrous proteins that create the thick bands. Single-cell technology allowed the researchers to determine that these cells secrete a signal that communicates with nearby T cells, causing them to migrate away from the cancer and towards the fibrous bands where they become sequestered.

“So, then we asked, what if we were to block this signaling in T cells with a compound?” Sethupathy said. The Pillarisetty team at the University of Washington used patient tumor slices to test this compound, called AMD3100, and found that it effectively mobilized T cells into the core of the tumor. Moreover, combining AMD3100 together with immune checkpoint inhibition further facilitated activation of T cells, leading to a significant increase in the death of tumor cells.

Sethupathy and colleagues are currently searching for liver cancer clinicians who might be interested in starting clinical trials for the new treatment. “A compelling feature of this work is that AMD3100 is already FDA-approved, which can reduce risks and potentially speed up timelines for clinical trials in fibrolamellar carcinoma,” Sethupathy said.

Co-first authors include Jason Carter and Lindsey Dickerson, both in the Pillarisetty lab at the University of Washington, and co-authors include Bo Shui, a senior research associate in the Sethupathy lab.

The study was funded by the Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe