Labor Action Tracker reports jump in health care strikes

By Julie Greco

While the number of U.S. work stoppages decreased overall by nearly 16% over the past year, the health care industry saw a 58.3% jump in work stoppages and a 151.9% increase in the number of workers involved, according to a report published Feb. 18 by the School of Industrial and Labor Relations and the University of Illinois School of Labor and Employment Relations.

The accommodation and food services industry saw 59 work stoppages – the highest number of any industry. But while the health care industry accounted for fewer strikes – 57 – it included the highest number of workers.

“The significant increases in work stoppages in health care are a signal of a number of factors joining together to create a labor-relations perfect storm,” said Ariel Avgar, Ph.D. ’88, director of the Center for Applied Research on Work.

Three major issues face health care workers, Avgar said: An immense pressure to improve patient care outcomes while simultaneously containing costs; frustrations about the gap between the post-COVID language of “essential workers” and actual working conditions; and economic headwinds and the rising cost of living.

“Taken together, health care-specific pressures, a frustration over the gap between the rhetoric of essentiality and the actual working conditions, I don’t expect this work-stoppage increase to subside in the near future,” said Avgar, the David M. Cohen Professor of Labor Law and History.

The increase in work stoppages among health care workers is one of “the more surprising findings” from the 2025 report, said Johnnie Kallas, Ph.D. ’23, who launched the Labor Action Tracker in 2021 and is now an assistant professor at the University of Illinois School of Labor and Employment Relations.

“Since 2022, the industry with the most striking workers has been the accommodation and food services sector, particularly food service workers,” Kallas said. Food-service strikes have declined because the number of individual strikes organized by Starbucks workers has declined, though many Starbucks workers have been on a nationwide indefinite strike since late 2025, he said.

“In general, health care strikes will be larger than the food-services strikes because the industry is both more heavily unionized, and workplaces are much larger.”

Kallas produced the report with Deepa Kylasam Iyer, a doctoral student in the field of global labor and work. Luke O’Brien ’27 is the report’s lead author.

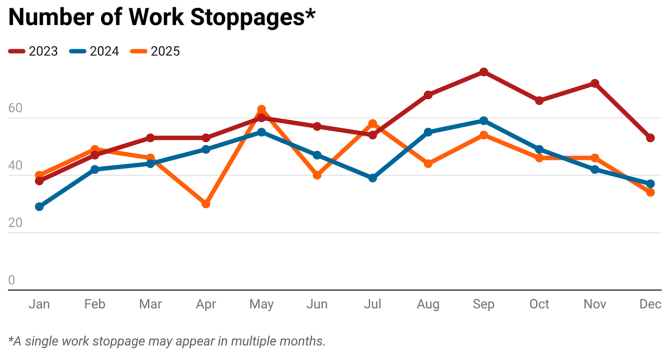

The number of work stoppages, while lower than 2024, is still well above work stoppage numbers seen in 2021, the report’s first year.

Key findings in the 2025 report:

- Last year’s 303 work stoppages – 298 strikes and five lockouts – are down 65 from the previous year’s 368, the second year of a decrease.

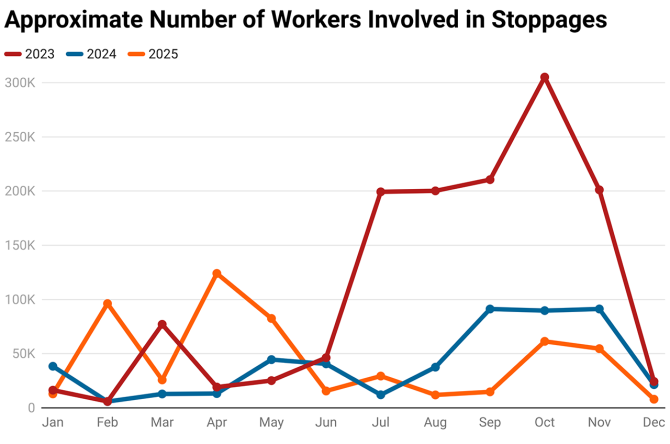

- The number of workers involved in strikes – approximately 290,000 – dropped by just over 3,000 in 2024.

- The health care industry increased from 36 work stoppages involving 46,369 workers in 2024 to 57 work stoppages involving 116,826 workers in 2025.

- The health care industry accounted for 40.3% of striking workers, ahead of public administration, which accounted for 29.6%.

- Health care also ranked first in strike days (1,213,703), nearly double the number of days by the manufacturing industry (684,773), which ranked second.

- The top reasons for work stoppages were pay (195), followed by first contract negotiations (70) and health care benefits (66).

- Nonunion workers organized 18.5% of all work stoppages, the lowest share since 2021.

- More than 77% of all workers on strike came from the Western United States.

“The West has accounted for an increasing share of the total workers on strike over the past three years,” Kallas said. “It’s also noteworthy just how many workers go on strike in the West compared to the rest of the country, which we can confidently say is driven by labor activism on the West Coast, particularly in California.

The increase in the number of first contract strikes is also important, he said, because it demonstrates that Starbucks workers and other newer unions are still fighting, and striking, for their first contract.

The Labor Action Tracker provides a comprehensive picture of nationwide workplace conflict, and is available to policymakers, practitioners, scholars and the public. It counts all work stoppages, regardless of size.

The tracker fills a data void: Stoppages of fewer than 1,000 workers aren’t included in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics database. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration cut funding for counting smaller stoppages.

Tracker data is collected from public sources, including existing work stoppage databases, news stories and social media posts.

Julie Greco is director of communications for the ILR School.

Media Contact

Adam Allington

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe