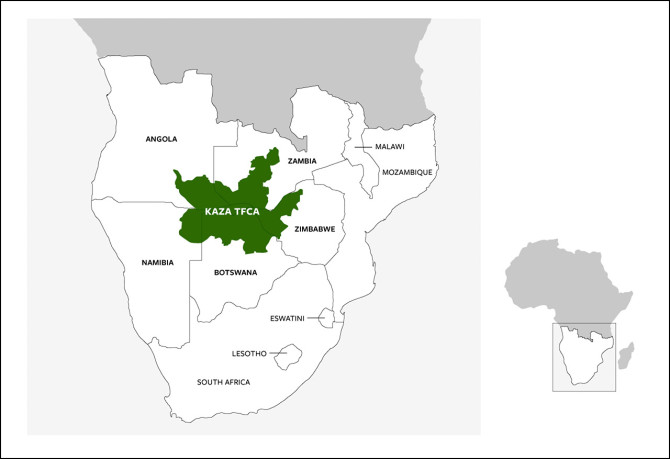

Zebra and wildebeest in southern Africa’s Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (pictured) are under threat due to veterinary fences and other land-use changes that restrict migrations.

Removing southern African fences may help wildlife, boost economy

By Krishna Ramanujan, Cornell Chronicle

Fences intended to protect cattle from catching diseases from wildlife and other livestock in southern Africa are in disrepair, restrict wild animal migrations and likely intensify human-elephant conflict – but a plan to remove key sections could make both livestock and wildlife safer, a new Cornell study suggests.

Across parts of southern Africa, fences aim to separate cattle from other animals to prevent the spread of diseases – most importantly, foot and mouth disease, which is a virus that can be spread to local cattle by wild buffalo or infected livestock.

The fence lines are not only in disrepair due to damage from elephants, but also from the elements and neglect due to the high costs to maintain them; they also restrict the free and vital movements of migrating wildlife – from zebras to wildebeest to elephants – leading to hundreds of thousands of wild animal deaths since the fences were first installed in the 1950s.

Now, a new study proposes a solution: Strategically remove sections of the fencing where disease risks to livestock are very low while promoting herding and other measures that protect cattle from pathogens. And in partnership with local and national government officials, the study’s authors are working to implement these measures in hopes that they will improve animal health and productivity, while also providing poor farming communities with additional income sources from a burgeoning wildlife tourism industry.

“The study’s results have gotten traction, with the government of Botswana agreeing to consider the possibility of removing some of the most damaging fences and thus restoring some of the most important wildlife migration routes in southern Africa,” said Steve Osofsky, D.V.M. ’89, the Jay Hyman Professor of Wildlife Health and Health Policy at the College of Veterinary Medicine and senior author of the study published Jan. 29 in Frontiers in Veterinary Science. Laura Rosen, a veterinary epidemiologist with the Victoria Falls Wildlife Trust in Zimbabwe, is the paper’s first author.

Southern Africa has experienced long-standing conflicts between livestock and wildlife going back to the late 1950s, Osofsky said. Two decades ago, Osofsky developed and launched the AHEAD (Animal & Human Health for the Environment And Development) program, which helps facilitate cooperation around issues affecting both wildlife and livestock.

“We bring parties together within countries, like ministries of agriculture and ministries of environment, but we also work very hard to create an enabling environment for dialogue across international boundaries,” Osofsky said.

Reviving cattle herding in Botswana will help reduce livestock disease risks.

In the 1950s, colonial powers, especially Britain and Germany, wanted to export beef from southern Africa back to Europe, Osofsky said. But, they knew that the foot and mouth disease virus was present in the region’s buffalo and was disastrous if livestock contracted it; to this day, outbreaks cause countries to lose access to international markets. In the following decades, thousands of miles of fences were built across the region to separate wildlife from livestock, so exported beef would not pose a risk of spreading the virus.

Today, nature-based tourism has become as or more important to the region’s economy as livestock agriculture, forestry and fisheries combined, Osofsky said.

“The poorest of the poor farmers tend to live closest to wildlife and they are the ones most damaged by policies that limit their access to beef markets over disease-related fears,” Osofsky said. “We also don’t want to compromise these migrations, which are crucial for wildlife, and wildlife is now the golden goose for this part of the world.”

The study focused on three specific sections of fencing within the 520,000 square kilometer Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), the world’s largest terrestrial transboundary conservation area, which extends across parts of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

In addition to foot and mouth disease, the researchers prioritized two other diseases: cattle-specific contagious bovine pleuropneumonia and peste des petits ruminants, a disease of goats and sheep. They also looked at the influence of buffalo poaching, by examining a scenario around whether poached meat is likely to spread foot and mouth disease (spoiler: it isn’t).

As part of Osofsky’s broader research program in partnership with KAZA countries like Botswana, an initial field and desktop study was done to identify which specific fences, if removed, would most benefit wildlife. Then, in the program’s second phase, Rosen led a team to evaluate the potential risks and consequences of pathogens crossing over fence lines and exposing livestock. They compared different scenarios that included the risks with fences as they are; whether risks might change if specific fence sections were removed; and the risks of fence section removal combined with mitigation measures, such as herding and improved vaccination.

“We found that the overall risk estimates of these diseases were generally very low,” Rosen said. “And we found there was no difference between the status quo and the fence-removal scenarios – the risk didn’t increase with fence section removal.”

“That was a key finding from a policy perspective,” Osofsky said.

“When removing specific sections of fencing was coupled with risk mitigation steps, the risk could potentially decrease,” Rosen added.

Herding, a practice that has waned in Botswana, safeguards against cattle wandering to places where they might interact with wild buffalo and other livestock. It also protects them from predation by lions and theft, and helps farmers keep track of cattle at times when they need vaccinations.

Most of the fence sections the researchers examined protect low densities of livestock, often with livestock on only one side of the fence, meaning the fences in these areas aren’t necessarily the most important ones for lowering disease risks. The researchers also pointed to evidence that foot and mouth disease may already be circulating in cattle within Botswana and may not be detected when animals don’t show clinical signs. “A fence may not be preventing the disease from coming into that population from buffalo or from cattle from another country, because it’s already there,” Rosen said.

The collaboration among government officers in Botswana and Namibia, the Victoria Falls Wildlife Trust and Cornell has inspired important dialogue under the auspices of KAZA, overcoming some of the historically controversial politics of fencing, Osofsky said.

In Botswana, the study has facilitated an agreement with government officials to explore changing the status quo. The research team and other local organizations are now working to assist communities in northern Botswana to implement herding and improve animal husbandry, vaccination and access to markets by producing disease-free beef that is recognized as safe to trade. In exchange, the government has agreed to consider removing specific fence sections to restore important migrations for wildlife, Osofsky said.

At the same time, these efforts help create more resilient livelihoods for the region’s poorest. The team’s guidelines are already leading to higher beef prices for what is being termed as wildlife-friendly beef, with the longer-term goal of boosting the wildlife economy and jobs in tourism.

The fences have also penned-in growing elephant populations, increasing the likelihood of more human-elephant conflict, including human fatalities, in agricultural areas. “If the fences are opened up, the net result will likely be a lower density of elephants over time in some of the high-conflict areas, decreasing that conflict, which is a very serious problem,” Rosen said.

Co-authors include Shirley Atkinson, a wildlife ecologist and regional coordinator for Cornell’s AHEAD program; Nlingisisi Babayani, of the University of Botswana; Mokganedi Mokopasetso, of the Botswana Vaccine Institute; Mary-Louise Penrith, of the University of Pretoria; Nidhi Ramsden, of Seanama Conservation; Janine Sharpe, of the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, Namibia; Thompson Shuro, of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Land Reform, Namibia; Odireleng Thololwane, of the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture, Botswana; and Jacques van Rooyen, of REHerd Africa.

The study was funded by the World Wildlife Fund, the Cornell AHEAD program, the Oak Foundation and Sue Holt, who has supported the AHEAD program.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe