Gerlinde Van de Walle in her lab at the Baker Institute for Animal Health.

Novel approach to udder infection is target of new project

By Patricia Waldron

Apart from antibiotics, dairy farmers have few tools to treat mastitis, a common and costly udder infection. Now, Cornell researchers are proposing an addition to their toolkit.

A team led by Dr. Gerlinde Van de Walle of the Baker Institute for Animal Health is exploring compounds secreted by stem cells as a potential therapy that may kill the bacteria while healing the damage they leave behind.

The new project stems from a collaboration between the Baker Institute, part of the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), and Indianapolis-based Elanco, a leading animal health company. Funding for the work comes from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), the New York Farm Viability Institute (NYFVI) and Elanco.

All told, the project will receive $1.38 million, with about half coming from FFAR. While the research is still in its early stages, the team hopes it will prove that stem cell compounds have potential for treating mastitis and perhaps other diseases.

“The long-term goal,” Van de Walle said, “would be a natural product that could be an adjunct or even a replacement for antibiotics. That in itself would be huge.”

“Infections like mastitis, common in dairy cattle, are a major concern among producers as these infections are costly and result in decreased milk production,” said Dr. Sally Rockey, FFAR’s executive director. “FFAR is thrilled to support this bold research. If the treatment is effective and affordable, it has the potential for adoption across dairy farms nationwide, resulting in enhanced milk production and farmer profitability.”

Besides impacting the health of cows, mastitis is a major economic problem for dairy farmers, according to team member Dr. Daryl Nydam, faculty director of the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability and professor of dairy health and production at CVM.

“Mastitis is the highest incidence disease and the costliest infectious disease of the dairy industry,” said Nydam. The infection causes a drop off in milk production and quality, he said, and if antibiotics are required, the milk must be discarded to prevent contamination of the milk supply with antibiotic residues.

While antibiotics are sometimes useful for clearing the infection, depending on pathogen, they can’t repair the resulting damage in the mammary gland, and so milk production levels may never recover. “We’re hoping this approach both rids the cow of the bacteria and restores closer to normal milk production,” Nydam said.

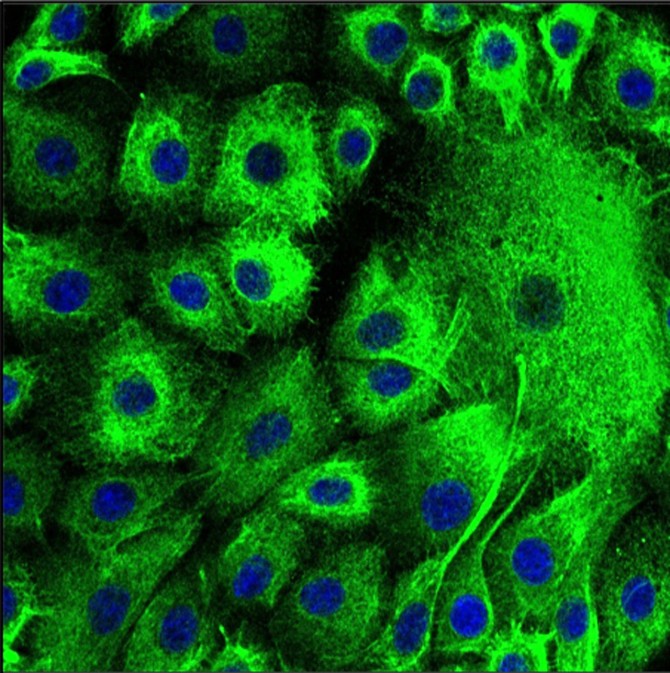

In a 2018 study in Scientific Reports, Van de Walle and Nydam used cell cultures grown in the lab to investigate the effects of the “secretome” – all secreted compounds – from adult stem cells from bovine mammary tissue. This work showed that the secretome had antimicrobial properties by killing bacteria; it also prevented damage from bacterial toxins, and promoted healing through the growth of blood vessels and recruitment of new cells.

Now, with help from Elanco, they will perform similar experiments with the secretome, but this time in cows.

“We find really amazing things in the lab, but we don’t always have the opportunity to continue working on it and pursue it in the live animal,” Van de Walle said. “Working with Elanco is crucial, because they have the facilities and cow models that will allow us to test these secreted biomolecules.”

Elanco got involved when Dr. Lucas Huntimer, a senior adviser for external innovation at the company, reached out to Van de Walle after reading the 2018 paper. He suggested applying to FFAR, a nonprofit that funds major agricultural research through public-private partnerships. To apply, however, the project needed equal contributions from research partners.

Elanco stepped up to offer financial support, and Drs. Huntimer and Leane Oliveira, a principal research scientist, and their team will be performing the in-cow experiments at their facilities.

“This is probably the most novel treatment approach for mastitis I have seen in my career,” said David Grusenmeyer, executive director of the NYFVI, a nonprofit organization that supports research to make New York farms more economically viable. The NYFVI board unanimously voted to support this new research after a thumbs-up from their review panel of dairy farmers.

Grusenmeyer said organic dairy farms would especially benefit from an alternative mastitis therapy, as they can’t use antibiotics for their cows. According to the Pew Research Center, New York had 471 organic dairy farms in 2016, the most of any state in the U.S.

In their experiments, the team plans to treat cows with mastitis using different components of the secretome, to pinpoint which bioactive compounds are responsible for its beneficial effects. In the treated cows, they’ll be looking for any antimicrobial effects; differences in milk production; signs of healing and regeneration of the mammary tissue; and changes in the bovine immune system that may help fight the infection.

The researchers will also be comparing the effects of different types of bovine stem cells. “There's so much unharnessed innovation in the area of stem cells and the secretome,” Huntimer said, “that it’s fun to have the opportunity to explore novel potential therapies that may come out of that.”

The research also has potential applications beyond mastitis, Van de Walle said. “If we find that naturally secreted biomolecules can both replace antibiotics and restore damaged tissue,” she said, “then this work could be expanded to other livestock, like pigs and chickens, and also other diseases.”

Patricia Waldron is a freelance writer for the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe