Morning sickness is Mother Nature's way of protecting mothers and their unborn, Cornell biologists find

As unpleasant as it is, the nausea and vomiting of "morning sickness" experienced by two-thirds of pregnant women is Mother Nature's way of protecting mothers and fetuses from food-borne illness and also shielding the fetus from chemicals that can deform fetal organs at the most critical time in development.

That is the conclusion of two Cornell University evolutionary biologists who examined the outcomes of thousands of successful and unsuccessful pregnancies. In the latest issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology (Vol. 75, No. 2, pp. 113-148, June 2000), Samuel M. Flaxman and Paul W. Sherman report that NVP (for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, as morning sickness is known in medical terms) serves a beneficial function. The finding helps explain why many pregnant women develop an aversion to meats, as well as to certain vegetables and caffeinated beverages, in early pregnancy and prefer bland-tasting foods instead.

Sherman and Flaxman believe their exhaustive analysis and synthesis of dozens of studies is the first to gather compelling evidence that morning sickness protects both the unborn and the mother-to-be.

"'Morning sickness' is a complete misnomer," says Sherman, professor of neurobiology and behavior at Cornell and co-author of the report, "Morning Sickness: A Mechanism for Protecting Mother and Embryo." "NVP doesn't occur just in the morning but at any time during the waking hours, and it's not a sickness in the pathological sense. We should change the name to wellness insurance."

Flaxman, a Cornell biology graduate student, says the analysis of hundreds of studies covering tens of thousands of pregnancies suggests that morning sickness and the aversion to potentially harmful foods is the body's way of preserving wellness of the mother at a time when her immune system is naturally suppressed (to prevent rejection of the child that is developing in her uterus) and has reduced defenses against food-borne pathogens.

By creating food aversion, NVP also protects against toxins from microorganisms and other teratogenic (fetal organ-deforming) chemicals, Sherman says. "At that same time, in the first trimester of pregnancy, the cells of the tiny embryo are differentiating and starting to form structures. Those developing structures and organ systems – such as arms and legs, eyes and the central nervous system – at this critical stage of a new life could be adversely affected by the teratogenic phytochemicals in some food plants," Sherman says. These chemicals are secondary compounds that plants make to defend themselves against disease and insects.

Although phytochemicals have no known nutritive function for humans, most people tolerate their presence in food. (Small amounts of these chemicals might even be beneficial because of their antioxidant properties and trace elements.) But during pregnancy, according to the Cornell biologists, women with morning sickness are shielding the developing unborn from the harsh chemicals by vomiting and by learning to avoid certain foods altogether until the fetus develops beyond the most susceptible stage.

Their other findings:

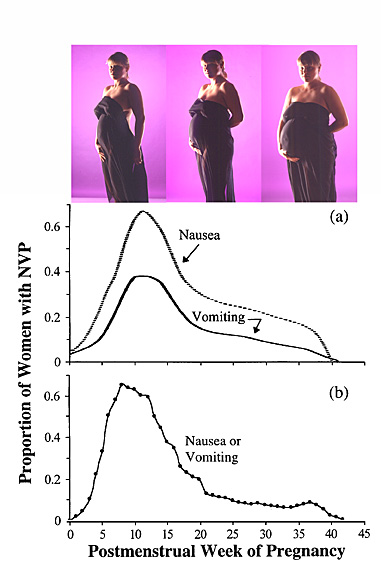

- Among women who experience morning sickness, symptoms peak precisely when embryonic organogenesis (organ development) is most susceptible to chemical disruption – between week 6 and week 18 of pregnancy.

- Women who experience morning sickness are significantly less likely to miscarry than women who do not. Women who vomit are significantly less likely to miscarry than those who experience nausea alone.

- Aversion to and avoidance of certain foods also peaks during the first trimester for many pregnant women. The most-observed aversion was to meats, fish, poultry and eggs – the foods that were more likely to carry harmful microorganisms and parasites before the advent of modern refrigeration and food-handling processes. Strong-tasting vegetables, as well as alcoholic and caffeinated beverages, also are disliked by many women.

- In seven traditional societies with virtually no morning sickness, animal products are not a dietary staple. Plant-based foods – and corn, in particular – were found to be the dietary staple in six of seven societies with little or no morning sickness. The edible parts of the corn plant, the kernels, have very low levels of phytochemicals.

The Cornell biologists acknowledge that previous researchers have proposed parts of the embryo-protection hypothesis and that alternative explanations for morning sickness have been advanced. These include hormones, mother-offspring genetic conflict, or communicating to nearby males and kin that women are pregnant (resulting in decreased sexual activity and increased help from family members). However, Sherman says, intercourse during the peak period of morning sickness, the first trimester, generally is not harmful for pregnant woman.

The genetic-conflict hypothesis predicts more morning sickness later in pregnancy (when the embryo is able to take resources), but, the biologists observe, morning sickness actually peaks early in pregnancy. Regarding the hormone hypothesis, Flaxman and Sherman say they are not disputing the role of these influential chemical signals from the mother's endocrine glands; rather, they are interested in why maternal hormones have the effect they do – prompting nausea and food aversions – instead of some other symptom, such as headaches.

Moreover, the Cornell biologists emphasize that their findings on the usefulness of morning sickness should not alarm women without NVP.

"Our analysis of thousands of pregnancies shows that most women in Western societies bear healthy babies whether or not they experience morning sickness," Sherman says. "The lack of NVP symptoms does not portend pregnancy failure any more than experiencing NVP guarantees that the pregnancy will have a positive outcome."

Instead, the Cornell biologists say, pregnant women and their physicians should derive a two-part message from the large-scale study of pregnancy outcomes:

- Attempting to alleviate the symptoms of "normal" (not severe) NVP probably will not improve the outcome of a pregnancy and could have the opposite effect if treatment interferes with the expulsion or avoidance of potentially dangerous foods.

- Encouraging women to eat foods they dislike during pregnancy will not improve the pregnancy outcome and could increase the embryo's exposure to pathogens and harmful chemicals.

"We are not suggesting that pregnant women cut meat and vegetables out of their diets. In other words, listen to your body," Sherman says.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe