‘Everything changed’: reuniting families fractured by opioids

‘Everything changed’: reuniting families fractured by opioids

By Susan Kelley, Cornell Chronicle

When her opioid addiction was at its worst, Stacey Dimas was terrified her sons, 3 and 10, would find her dead from an overdose in the family bathroom. She wrote them each letters with life advice in case they had to carry on without her.

“There’s an extra layer, when you’re using, of incomprehensible demoralization – those are the only words I have to describe it,” Dimas says. “I hated what I saw in the mirror. I didn’t think I was a good parent. In fact, I knew I wasn’t a good parent. And obviously the courts agreed with me.”

Dimas lost custody of her kids in 2015, after her mother and mother-in-law reported her to Child Protective Services for neglect. The boys went to live with her in-laws. Dimas was referred to Tompkins County Family Treatment Court.

Dimas and her children are among the hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers whose lives have been ravaged by opioid abuse. The epidemic spurred Cornell researchers and parent educators to analyze the opioid crisis’ impact on families and find solutions to treat parents who misuse opioids.

In traditional child welfare courts, parents take longer to start substance abuse treatment, return to drug abuse more quickly and are less likely to reunite with their children. Tompkins County Family Court, which incorporates Cornell programming, follows a therapeutic approach to family reunification. The Tompkins County collaboration inspired an ambitious five-year research program, the Opioids and Family Life Project, launched by Cornell researchers in 2018. The team is evaluating how the court’s use of a parenting class called Strengthening Families, run by Cornell Cooperative Extension (CCE) Tompkins County, helps strengthen and reunify families fractured by opioids, by teaching them skills from solving problems to coping with anger.

With CCE’s data-informed guidance at its core, the Tompkins County Family Court has become a model for New York state and the nation. Since 2018, the court has been one of eight peer-learning courts around the country, offering guidance to other family treatment courts from West Virginia to Guam, through a program run by Children and Family Futures, a child-welfare nonprofit.

“As a society, we haven’t thought a lot about what it means to be a parent who’s struggling with opioid addiction and what supports are needed for parents to be able to thrive in that role,” says Rachel Dunifon, the Rebecca Q. and James C. Morgan Dean of the College of Human Ecology (CHE) and a co-principal investigator on the project, along with Anna Steinkraus of CCE Tompkins County. “We can’t look at parents in isolation and look at the kids in isolation. We have to think about them together, and what they need as a family.”

The CCE Tompkins County team is hoping to spread its findings to other communities, in New York and the nation. It has researched and created a database of evidence-based parenting programs that support families facing challenges with substance use for extension educators around the country. And it aims to improve Strengthening Families by incorporating diversity, equity and inclusion in the curriculum. In mid-September, Steinkraus and other CCE staff ran a workshop on inclusive parenting education for parent educators from around the state, as part of the grant.

“My hope is that kids, for all the struggles that they may be facing, at the end of the day will feel that they have a parent in their lives who can really be there for them,” Dunifon says.

Once Dimas began taking the Strengthening Families program, her relationship with her children improved, she says. “Everything changed.”

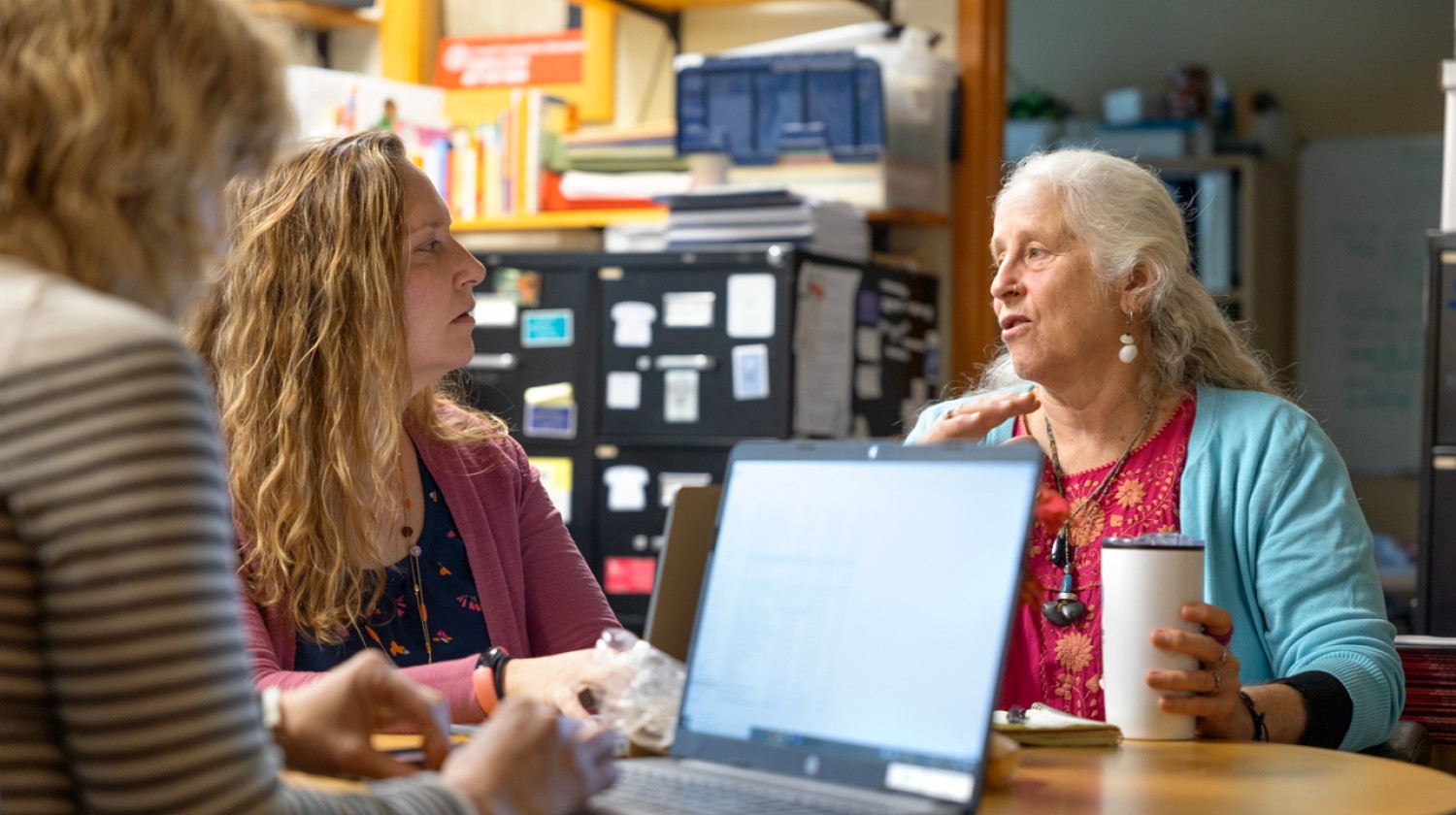

Laura Tach, left, associate professor of public policy and of sociology in the Cornell Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy, talks with Anna Steinkraus, family and community development program coordinator at CCE Tompkins County.

A new model of research

In 2002, Dimas was 20, living in California, going to community college off and on, and drinking and using cannabis daily. That year, while drunk, she got in a fight with a man who lacerated her liver. She almost died from internal bleeding. Her doctor prescribed her narcotics for the pain. “I was able to figure out there’s a wonderful combination where I could get this really great high but still be functional,” she says.

More surgeries, for ovarian cysts and kidney stones, meant more opioid prescriptions. “And so it just kind of snowballed from that,” she says.

In 2014, seeking a new start, she moved her young family to Ithaca. But her problems followed. New York state doctors were less willing to prescribe opioids, so Dimas switched to cheaper illegal substances.

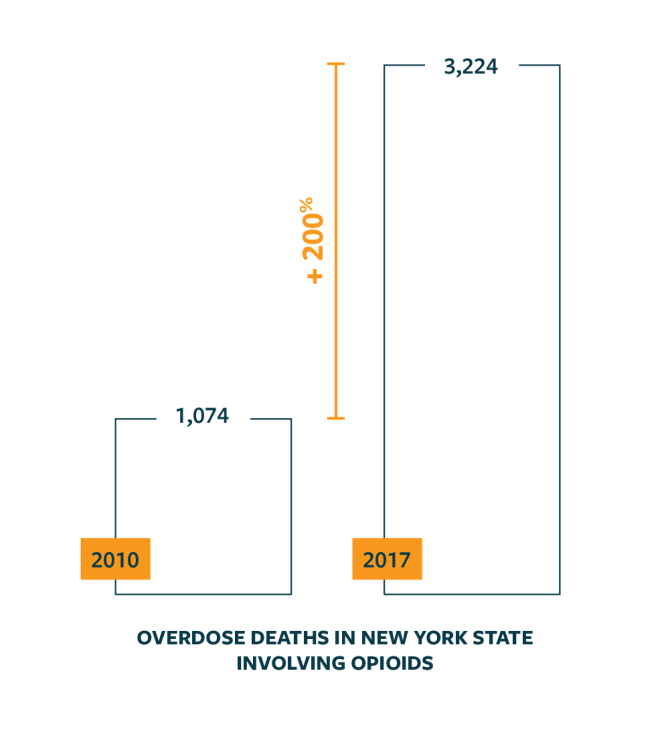

Overdose deaths in New York from opioids – prescription drugs such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, and illegal drugs including heroin and fentanyl – skyrocketed 200% between 2010 and 2017.

Source: New York State Opioid Annual Report 2021, p.11

In 2017, opioids were hitting families hard in Tompkins County, says Steinkraus, who coordinates CCE’s parenting programs in the county. “They were being drawn into social services, generally more around [child] neglect, because their involvement with opioid use was making it hard to be focused on parenting,” she says.

Steinkraus talked about these disturbing developments with Laura Tach, associate professor of public policy and of sociology in the Cornell Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy.

“We decided that we needed a stronger research base to understand how families and children were being affected by the increase in opioid use nationwide, but also in our state and county – and what were the best practices to support families,” Tach says.

To do that, the team was awarded the William T. Grant Foundation’s first Institutional Challenge Grant in 2018. The award came with $650,000 over three years, to respond to increasing rates of opioid use and child maltreatment in low income, rural communities in New York state. Thanks to the success of their work, the foundation extended the grant in 2021 for two years.

The Opioids and Family Life Project, housed in CHE’s Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research, represents a new model of research, because it was created collaboratively with the CCE Tompkins County team, Dunifon says. “Their on-the-ground experiences allowed us to conduct really important groundbreaking scientific research that’s based on what’s happening in our community,” she says. “It makes the work we do more relevant, more nuanced and more impactful toward our ultimate goal, which is improving the lives of people in our local community, in New York state and around the world.”

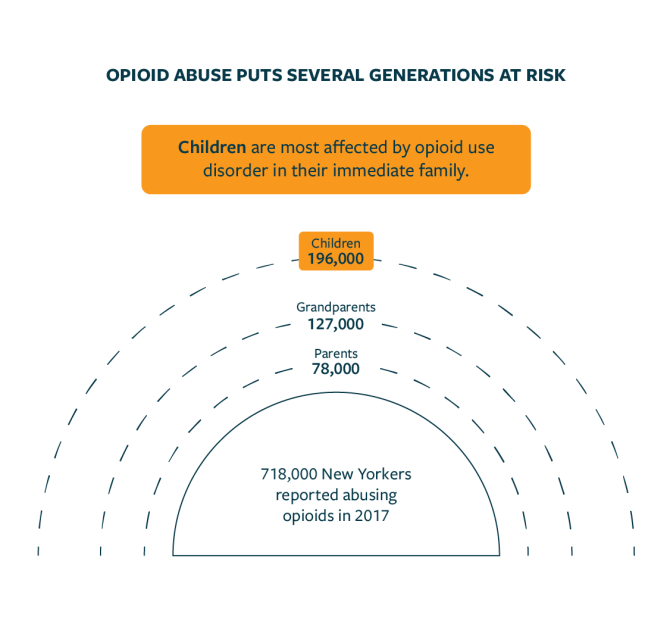

The researchers have found opioids affect 1 in 12 New Yorkers, or more than 8%, directly or indirectly, through their immediate family members. They also found that since 2010, over a 10-year period, the rate of both opioid misuse and family members being affected increased by over 100%.

And they’ve identified an association between rising rates of opioid misuse and child maltreatment in New York state. From 2006-16 those rates were geographically concentrated in western and central New York, the Finger Lakes region and the Southern Tier, which includes Tompkins County and Cornell’s Ithaca campus.

Not all parents who misuse opioids mistreat their children, Tach says. “We don’t want to stigmatize people. But increased child welfare caseloads are a practical consequence that a lot of counties are facing.”

John Rowley ’82, founding judge at the Tompkins County Family Treatment Court, takes a holistic, strength-based approach to motivating parents to improve their lives and the lives of their children.

‘An extremely important resource’

Tompkins County had a 14% increase in overdose deaths involving opioids from 2020 to 2021.

The opioid epidemic is the main reason the number of cases in the county’s Family Treatment Court has more than doubled, from 30 in 2001, when the court was founded, to 75 so far in 2022, says John Rowley ’82, the court’s founding judge. About 75% of neglect cases involve substance abuse, most often opioids; parents frequently start out misusing prescription drugs and then switch to heroin because it is cheaper, he says.

“What we’re most concerned about is … it’s a complete disconnect from your environment,” Rowley says of opioids’ effects. Parents who misuse opioids “are not generally functioning in any significant way. Certainly, the emotional engagement is impaired.”

The biggest effect? “Their addiction becomes their primary relationship,” he says. “And that means everything else is secondary” – including their children.

For Dimas, opioid use prevented her from being emotionally available for her sons. “They were in my way when I was using; there’s no question about that,” she says. “If I wanted to go out to the club and dance or whatever, they were in my way.”

Parents who misuse opioids might drop off their children with someone and fail to come back when they said they would, Rowley said. They’re unable to get their kids to school. They don’t give their children enough food or emotional support. Sometimes they use harsh discipline. Older children may take care of siblings in their parents’ absence or take on household chores beyond their capacity.

Parents often think their kids are unaware of their opioid misuse. But children do know, Rowley says. “[They’ll say] ‘I could tell Mom was talking fast.’ ‘Mom was in the bathroom for a really long time.’ ‘Dad really tried to hurry us through dinner. Whenever he tries to put us to bed fast, we know something’s going on,’” Rowley says.

From 2010 to 2019, the number of deaths involving fentanyl in New York state increased

The Strengthening Families program, created in the 1980s at the University of Utah, aims to change those family dynamics. It is one of several strength-based milestones the Tompkins County Family Treatment Court requires parents to complete in order to be reunited with their children. Parents usually take a year to 18 months to reach all the milestones, which include substance abuse treatment; ongoing monitoring of the family; getting medical, dental and mental health care; and securing adequate food and housing. The court offers support, such as access to social workers and referrals to local service agencies.

Parents are allowed to see their children as often as resources allow; often those visits occur at a Strengthening Families session. As parents reach each milestone, they get to see their children more frequently until they are reunited.

The Cornell team’s research shows family treatment courts are associated with more positive outcomes for children and families. In her senior honors thesis, research team member Pearlanna Zapotocky ’21 found that children in family treatment courts are more likely to be reunified with their parents, who are more likely to be in recovery and stay in recovery for longer periods of time, Tach said. And the CCE Strengthening Families program was especially linked to positive outcomes for families, she found.

CCE programming “is an extremely important resource to us,” Rowley says. “It’s because these evidence-based programs, they actually work. Our parents experience it, we experience it. So we just keep building on that.”

Stacey Dimas says the Strengthening Families program helped her to expand her emotional connection with her children.

A disease of isolation

Going into the Strengthening Families program, Dimas felt she already had the tools to be a good parent. “It’s a common reality for most parents [to think], ‘Of course I know how to parent a child. How hard can it be?’” she says. “In all actuality, it’s very hard.”

It’s even harder when parents are struggling to find housing, transportation, food and medical care – all while trying to stay sober. When she started Family Treatment Court, she was living out of her car, had no friends, no family. She and her husband had split up. “They say addiction is a disease of isolation,” Dimas says. “And I absolutely believe that to be true. … The only things I had, when I left detox for the second time, were the clothes that I took to detox and the blanket that I stole.”

And parenting is harder still when people are also dealing with their own traumatized childhoods, says Mandy Beem-Miller, who runs Strengthening Families as the family and community coordinator for the Cornell Project 2Gen, which builds family well-being by simultaneously working with children and parents. “We always say, ‘You only know how to parent the way you were parented,’” she says. “It always comes up, how they were parented. There’s a lot of trauma there.”

Childhood trauma was a daily occurrence for Dimas. She was raised by a single mother who herself was traumatized by violence and civil unrest in her home country, El Salvador. Her mother also had an undiagnosed bipolar disorder and was often suicidal and institutionalized.

They moved frequently. Dimas went to 15 different schools – so many that by elementary school she gave up making emotional attachments. By age 12, she was drinking daily, getting into fights, running away from home and hanging around dangerous people in dangerous neighborhoods. “I thought I was hard as heck,” she says. “By the time I was in eighth grade, I was a very angry little person.”

Strengthening Families aims to help parents create the family routines and communication they never had as children.

“We’re trying to shift the role back to giving authority to the parent, where trust has been lost with their children. They need to rebuild and repair that,” Beem-Miller says.

The sessions focus on the power of play, kids’ abilities by age, how to manage stress, using praise to encourage good behavior and healthy communication. Families also learn about the harm of drugs and alcohol, recognizing feelings, and dealing with criticism.

“These skills are really designed to open the doors of communication so that you can be the person your child comes to talk to when they’re struggling with something, and they know they’re not going to get shut down,” Steinkraus says.

Typically groups of families start each session with a family-style meal. Then they separate into a one-hour parent class and a child class where they focus on a particular skill or topic. During the second hour, parents and kids come back together to practice the skill through an activity. Since the pandemic, CCE Tompkins County has pivoted to one-on-one sessions with a facilitator, a parent and child.

Many parents say they especially benefited from learning about the stages of children’s social and emotional development, Beem-Miller says. “A huge frustration with parents is when they mismatch their expectation for the child with what their child is actually capable of.”

The skills helped Dimas to expand her emotional connection with her children, who are now 11 and 17. “I do see that they are willing to be vulnerable with me, and tell me their fears or anxieties or worries,” she says.

Stacey Dimas attends her oldest son’s football game at Ithaca High School in Ithaca, New York, with her fiancé, Ariel Casper.

A two-generational approach

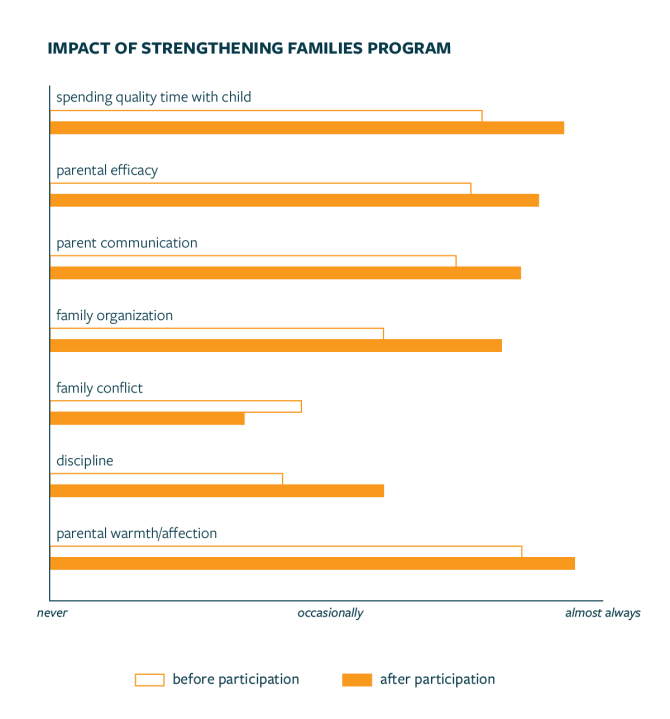

The research team found that parents in the court who participated in Strengthening Families reported significant improvements in parenting skills, from communication to warmth and affection and managing family conflict.

Source: "Benefits of Incorporating the Strengthening Families Program Into Family Drug Treatment Court Services," Journal of Extension, Oct. 2020, Vol.58, No.5, Article #v58-5rb2.

Why does it work? The two-generational approach, Tach says. “There are these positive multiplier or amplifying effects when you intervene to support both parents and children together, rather than focusing on just one in isolation,” she says.

Adds Steinkraus: “It has been life-changing for some families, where it has really completely changed their approach to how they parent.”

After graduating from Tompkins County Family Court, Dimas was reunited with her children in 2016. She and her husband divorced. She has been sober for more than seven years, since February 2015. And she mentors others in recovery.

Today, she is employed as senior adviser for People for the American Way, a progressive advocacy organization, where she focuses on reimagining public safety. She volunteers in leadership roles with community organizations including the Tompkins County Democratic Committee, Family and Children’s Service of Ithaca and the Women’s Fund of Central New York. She is engaged to be married. She has a bachelor’s degree.

“People always ask, how did you do it?’” she says. “I realized I needed help. And I asked for it. And lastly I accepted it.”

And she was surrounded by a community that offered that help, she says, through the programs of Family Treatment Court, she says. “I don’t think I could have gotten sober and built the foundation I’ve built in any other community.”

Dimas now knows all of her kids’ teachers and principals. She recently took her oldest boy, a senior in high school who plays varsity football, on a college tour. She made signs for him and cheered him on with her fiance. And on her 11-year-old’s first day of middle school, she emailed his teachers to let them know it was his birthday.

“Now they’re no longer in my way,” she says. “And I get to enjoy their journey.”

This story and video were developed and produced by Susan Kelley and Ryan Young, with support from Matt Fondeur, Eduardo Merchán, Ashley Osburn and Marijke van Niekerk. It was edited by Lindsay France and Melanie Lefkowitz.

Media Contact

Abby Kozlowski

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe