First Cornell ornithologist to see ivory-bill in Arkansas bayou describes thrill and emotion of discovery

Tim Gallagher, editor of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's award-wining quarterly, Living Bird, and author of the forthcoming book, "The Grail Bird: The Search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker," was the first ornithologist from Cornell University to positively identify an ivory-billed woodpecker in Arkansas' Bayou de View. Here he recounts the thrill of that Feb. 27, 2004, sighting, as well as earlier near-misses that fueled his "obsession with this bird" and the organized search that followed his discovery.

ITHACA, N.Y. -- I first became interested in the ivory-billed woodpecker after reading a 1972 article in Life magazine about John Dennis' 1966 sightings of the bird in the Big Thicket area of east Texas. His sightings are still surrounded with controversy and have not been universally accepted, but his work did inspire a great deal of interest in the bird and its habitat.

The following year, during a trip with a friend to watch migrating peregrine falcons on the coast of Texas, we made a foray into the Big Thicket, hoping to spot an ivory-bill. We found a vast morass of swamp and second-growth timber and quickly realized what a daunting task it would be to find one of these birds.

During the years that followed, my obsession with this bird lay dormant as I got involved in the peregrine falcon population recovery effort. Then the obsession would flare up again every time I heard about another possible sighting or visited a southern swamp. It was David Kulivan's 1999 sighting in Louisiana's Pearl River Wildlife Management that finally pushed me over the edge. Ever since, I've been consumed with tracking down every lead, interviewing every person I could find who might have seen an ivory-bill.

Kulivan's sighting seemed so believable and so hopeful. Just to imagine that we might have one more chance -- to rescue this bird and restore the southern bottomland swamp forests -- was an amazing dream come true. I'm sure a lot of other people who admire this bird felt the same way, which made it all the more crushing when no one else was able to find an ivory-bill there, despite massive search efforts and the installation of a dozen Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs) by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

I didn't want to let go of that dream, and so I started spending vacations in the South, exploring swamps. Traveling sometimes alone, more often with fellow ivory-bill searcher Bobby Harrison of Alabama's Oakwood College, I slogged through miles of swamp-forest habitat in Louisana, Mississippi, Florida and Arkansas. I interviewed everyone I could find who had actual first-hand experience with ivory-bills, trying to glean information that might help me with my search.

I visited Richard Pough shortly before his death at the age of 99 and spoke with him about the female ivory-bill he found in 1943. I visited James Tanner's widow twice to learn more about the birds she had seen in 1940 and 1941 in Louisiana's Singer Tract. I spoke with two men who had lived there as children and remembered the ivory-bills well. And I tracked down the mysterious photographer who had taken the controversial 1972 snapshots of a male ivory-bill. Many scientists at the time thought his photos were a hoax. After a lengthy in-person interview, I found his story to be credible.

In addition, I interviewed a woman who insisted she had seen an ivory-bill in the White River National Wildlife Refuge in March 2003 and a man who heard an ivory-bill-like call there during the same week. (These reports had prompted the Cornell lab to install three ARUs at the site that summer, but the recordings obtained there were inconclusive.)

Bobby Harrison and I spent part of a vacation there in January 2004, exploring the bottomland forest, some of which is old growth. We found several examples of bark strips peeled from trees in classic ivory-bill fashion. Our colleague, David Luneau of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, had also been working in this area and had an automatic camera setup aimed at one tree that had peeled bark.

Just a couple of weeks after we had been at White River, I heard about a kayaker (Gene M. Sparling III) who had seen an unusual woodpecker -- one with the diagnostic color pattern of an ivory-bill -- in a narrow bayou in northeastern Arkansas. He had seen it on Feb. 11, 2004. I called him up and grilled him about the sighting and found him entirely credible. Looking at a map, I saw that this area, called Bayou de View, was only about 50 miles from the spot where we had been searching in the White River refuge. And Bayou de View was connected to the refuge with a nearly continuous strip of woods.

Because of our previous interest in this area, we greeted his report with enthusiasm and a sense of urgency. Barely two weeks after Sparling's sighting, Bobby Harrison and I joined him on what we had planned to be a several-days-long float down Bayou de View.

On Feb. 27, 2004 (the second day of our trip), at approximately 1:15 p.m., a large black-and-white woodpecker with the characteristic color pattern of this species flew across the bayou at close range in front of Bobby and me. We cried out simultaneously, "Ivory-bill!" and paddled frantically toward shore. As soon as we landed, we took off through the boot-sucking muck and mire of the swamp, climbing up and over fallen trees and through branches, with camcorders in hand and running. Although the bird landed on tree trunks briefly a couple of times, we weren't able to catch up with it or take a video.

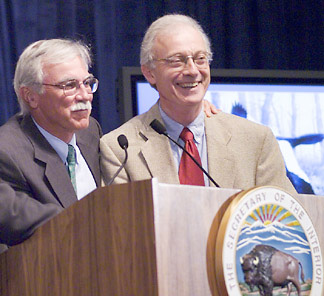

Fifteen minutes later, I suggested that we sit down and write detailed field notes, before we'd had a chance to think much about what we had seen or to confer with each other. As he finished his notes, Bobby sat down on a log, put his face in his hands and began to sob. "I saw an ivory-bill," he said. "I saw an ivory-bill." I stood quietly a few feet away, too choked with emotion to speak.

Sparling, who had been scouting well ahead of us, had just returned a few minutes earlier. We paddled downstream together to a good campsite he had found. We dubbed the place Camp Ephilus II in honor of the camp Arthur Allen had set up within sight of an ivory-billed woodpecker nest in Louisiana, during the 1935 Cornell expedition. Although we spent several more days searching, we did not have another definite encounter with the ivory-bill.

Within days of our sighting, the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology began rotating teams of researchers into the area, and this continued through the late winter and spring. (A handful of people hung tough through the hot, muggy, buggy, snake-infested summer.) The Cornell team worked closely with several Arkansas researchers to document the presence of the bird and determine whether any others are present. The lab also installed ARUs up and down the bayou. Several search team participants -- including field biologists from Cornell -- saw the bird, but the most solid documentary evidence from that field season was a video recording made by David Luneau on April 25, 2004, which shows a large black-and-white woodpecker peering out from behind a tree. Then it flies off through the swamp, exhibiting the distinctive color pattern of an ivory-billed woodpecker.

The new field season began in early December 2004. Teams of searchers fanned out into Bayou de View and the White River National Wildlife Refuge, installing ARUs in both areas. Several double-rap sounds, similar to those made by other Campephilus woodpeckers to announce their presence, were detected by ARUs in Bayou de View in late December and January. Analysts back at the lab in Ithaca worked to compare the latest recordings with archived double raps of all the other species in this genus. And an ARU at the White River recorded an intriguing series of calls, very similar to the ivory-bill calls recorded by the Cornell expedition in 1935.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe