Warming temperatures push chickadees northward

By Hugh Powell

The zone of overlap between two popular, closely related backyard birds is moving northward at a rate that matches warming winter temperatures, according to a study by researchers from Cornell and Villanova universities. The research will be published online in Current Biology March 6.

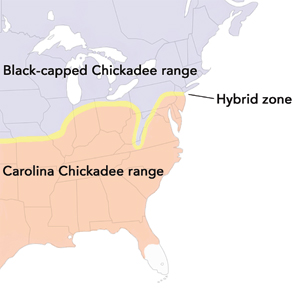

In a narrow strip – called a hybrid zone – that runs across the eastern U.S., Carolina chickadees from the south meet and interbreed with black-capped chickadees from the north. The new study finds that this hybrid zone, a convenient reference point for scientists tracking environmental changes, has moved northward at a rate of 0.7 mile per year over the last decade. That’s fast enough that the researchers added an extra study site partway through their project.

“A lot of the time climate change doesn’t really seem tangible,” said lead author Scott Taylor, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “But here are these common little backyard birds we all grew up with, and we’re seeing them moving northward on relatively short time scales.”

The researchers drew on field studies, genetic analyses and crowdsourced bird sightings. First, detailed observations and banding data from sites across the hybrid zone provided a basic record of how quickly the zone moved. Next, genetic analyses revealed in unprecedented detail the degree to which hybrids shared the DNA of both parent species. And then crowdsourced data drawn from eBird, a citizen-science project run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, allowed the researchers to expand the scale of the study and match bird observations with winter temperatures.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 167 chickadees – 83 collected in 2000-02 and 84 in 2010-12. Using next-generation genetic sequencing, they looked at more than 1,400 fragments of the birds’ genomes to see how much was black-capped chickadee DNA and how much was Carolina.

The site that had been in the middle of the hybrid zone at the start of the study was almost pure Carolina chickadees by the end. The next site to the north, which Robert Curry of Villanova University, who led the field portion of the study, and his students had originally picked as a stronghold of black-capped chickadees, had become dominated by hybrids.

Female Carolina chickadees seem to be leading the charge, Curry said. Field observations show that females move on average about 0.6 miles between where they’re born and where they settle down. That’s about twice as far as males and almost exactly as fast as the hybrid zone is moving.

As a final step, the researchers overlaid temperature records on a map of the overlap zone, drawn from eBird sightings of the two chickadee species. They found the zone of overlap occurred only in areas where the average winter low temperature was between 14 and 20 degrees Fahrenheit. They also used eBird records to estimate where the hybrid zone had been a decade earlier and found the same relationship with temperature existed then. The only difference was that those temperatures had shifted to the north by about seven miles since 2000.

“The rapidity with which these changes are happening is a big deal,” Taylor said. “Small mammals, insects and definitely plants are probably feeling these same pressures – they’re just not as able to move in response.”

In addition to Taylor and Curry, authors include Valentina Ferretti of Villanova University and Thomas White, Wesley Hochachka and Irby Lovette of Cornell.

Hugh Powell is a science editor at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe