Researchers find core genes for plant-fungal symbiosis

By Patricia Waldron

A new study by researchers at the Cornell-affiliated Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI) has uncovered a veritable trove of genes used by plants to form symbiotic relationships with fungi – an interaction that could be optimized through crop breeding to improve yield and reduce the need for fertilizers.

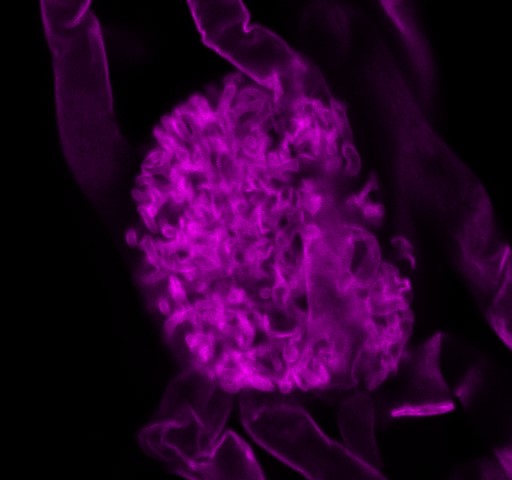

Most land plants get a large portion of their mineral nutrients through a symbiotic relationship with soil fungi called arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis. But, despite decades of research, many of the genes required to form this relationship remain elusive. Now, with the advent of widely available genome sequences, BTI researchers compared 50 plant genomes to identify 138 genes shared exclusively by plants capable of AM symbiosis. The findings appear in the journal Nature Plants.

“Currently, our research field has identified only a handful of genes required exclusively for AM symbiosis and we know that there are huge gaps in our knowledge,” said senior author Maria Harrison, the William H. Crocker Professor at BTI. “These 138 genes are a valuable resource and provide new insights into the ways that plant cells host their fungal symbionts.”

In the past, researchers have identified genes involved in AM symbiosis through time-consuming genetic screens that could take up to five years to complete. Having identified a few genes from the barrel medic plant (Medicago truncatula) through this approach, the researchers noted that several of these AM symbiosis genes are missing from another plant species that does not host the fungi. This realization inspired Nathan Pumplin, a former graduate student in the Harrison laboratory, to initiate a genome comparison approach in the hope of identifying more genes that fit this pattern.

“The approach relies on the idea, supported by fossil evidence, that AM symbiosis evolved just once, early on in the evolution of land plants, so all plants that host the symbiosis likely inherited a similar set of genes,” said Armando Bravo, a postdoctoral scientist and first author on the paper, who continued to develop the project. “Plant groups that lost the ability to form symbiosis are presumed to have lost the required genes.”

Bravo collaborated with Thomas York, a bioinformatics analyst at BTI, to compare the genome sequences of 34 plant species that can form the symbiosis with 16 that can’t. Together, they picked out the genes that are found only in plants that form AM symbiosis and from an initial list of 62,000 possibilities, arrived at just 138 genes.

Fifteen of these were already known to play a role in AM symbiosis and Bravo tested the accuracy of seven of the unknown genes in the group by growing barrel medic with mutations in those genes and examining their ability to form a successful symbiosis. Mutations in six of these genes resulted in a faulty interaction.

Analysis of the new genes highlighted the importance of lipid biosynthesis during symbiosis. While the analysis cannot single out every gene that a plant needs for symbiosis, it did pick out the ones that serve no other function.

“I think it really shows you the power of bioinformatics,” said Lukas Mueller, a coauthor and associate professor at BTI. “If you have lots of genomes you have much more power to answer questions.”

Patricia Waldron is the staff science writer for the Boyce Thompson Institute.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe