Eisenberg Research Fellows carry on namesake’s legacy

By Sherrie Negrea

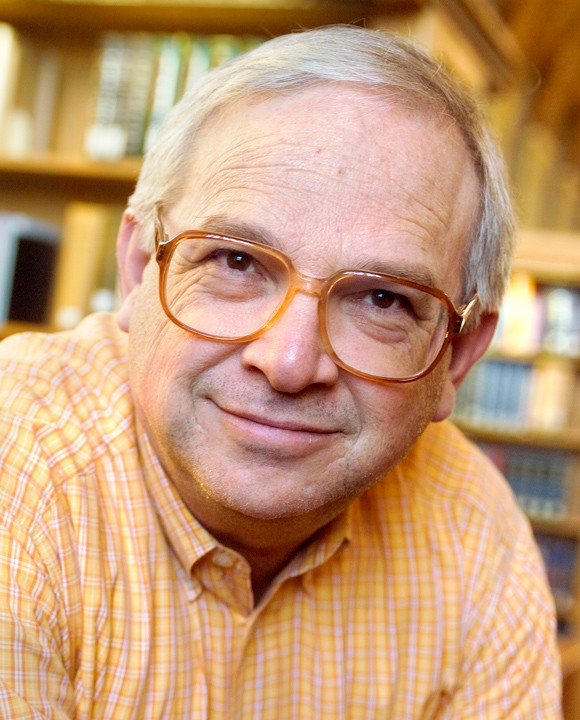

Six years after the untimely death of Theodore “Ted” Eisenberg, professor of law at Cornell Law School, a group of students is carrying on his pioneering legacy of empirical legal research through a new fellowship program.

The Eisenberg Research Fellows program was created after more than 50 donors contributed to a memorial fund honoring Eisenberg, one of the founders of the field of empirical legal studies. Empirical research in law involves the direct study of the institutions, rules, procedures and personnel of the law, in an effort to understand how they operate and what effects they have.

The fund was endowed by Drew Ranier, the founding partner of Ranier Law Firm LLC, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, who worked with Eisenberg on numerous legal cases using his data-driven approach to litigation.

Over the past year, the inaugural group of Eisenberg Research Fellows has been working with Law School faculty on empirical legal studies projects, ranging from an analysis of the decline in cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court to a global survey of lay participation in criminal trials, either on juries or mixed courts, where citizens decide cases with judges.

“We thought Ted would have really liked the idea of naming Eisenberg Research Fellows, which represents a commitment to empirical research and also the training of the next generation in these methods,” said Valerie Hans, the Charles F. Rechlin Professor of Law. “That seemed like a perfect use for the memorial fund.”

Eisenberg, who died in 2014 at age 66, was the Henry Allen Mark Professor of Law and an adjunct professor of statistical sciences. In a career of more than 30 years at the Law School, Eisenberg’s groundbreaking applications of statistical methods to legal processes earned him the unofficial title “grandfather of empirical legal studies.”

The fellowship program created in his honor was developed by a group of six Law School faculty members and Martin Wells, chair of Cornell’s Department of Statistics and Data Science, who are all editors of the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, which Eisenberg founded in 2004.

“This has been a tremendous benefit for any of the empirical legal scholars at Cornell because we get to involve very talented young people in our work,” said Dawn Chutkow, Ph.D. ’09, a visiting professor of law and the journal’s executive editor. “And even more important than that, it exposes our students to a really vibrant area of legal research, which they might not normally get exposed to.”

Alessandra Scalise ’20 became one of the first Eisenberg Research Fellows last spring after taking a class with Hans and using empirical research on a paper exploring how many countries in the International Criminal Court have a jury system. Since then, Scalise has been helping Hans to develop the first comprehensive empirical survey of lay participation in criminal trials worldwide.

The focus of Scalise’s research is determining the existence and types of lay participation in the criminal court system in the 54 countries of Africa.

“It’s not that often that you get to look into something that you’re really interested in and have someone there as a field guide when you have questions,” Scalise said. “That’s why it’s been really wonderful to work with Professor Hans.”

Kasaundra Riley ’21, another Eisenberg Research Fellow, began working with Chutkow last fall on a project analyzing the causes of the Supreme Court’s shrinking docket. Since the 1980s, the number of cases decided by the Supreme Court has dropped from 150 a year to 68 for the 2017-18 term.

“The research made it very clear that this is a continuing and sustained decline,” Chutkow said. “We really don’t know why; … that’s why we’re researching it.”

While legal scholars have suggested that the political leanings of the justices may have resulted in a decline in the caseload, Chutkow is using data analysis to determine if there are other possible explanations. As part of the project, Riley has been collecting data on each court term since the 1940s, looking at the length of time each justice has served and the relationships the justices have on the court.

“I think it’s really interesting to say, ‘Let’s look at the data and make sure that there’s not something else going on that we might not be aware of,’” Riley said. “I just think it’s cool to verify these hypotheses with data.”

Sherrie Negrea is a freelance writer for the Cornell Law School.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe