Administrators knew Cornell could host in-person classes only if students could sit at least 6 feet apart; they turned to the School of Operations Research and Information Engineering to optimize the university’s classrooms.

Model makers: How engineers saved the fall, spring semesters

By Syl Kacapyr

As the spring semester begins, a team of engineering students and faculty has finished tweaking the master schedule, using lessons they learned last fall during their heroic effort to help Cornell have safe, in-person classes.

University leaders faced a critical question in April 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic surged and they contemplated an in-person fall semester: Would it even be possible?

It was a question universities across the nation were grappling with as they tried to imagine what a safe, residential semester would require. Not only would Cornell need to establish a virus-testing protocol, but health guidelines would call for students to sit at least 6 feet apart, drastically reducing the university’s classroom space.

Exactly how much classroom space did Cornell have to work with? And could it accommodate any kind of course schedule?

It was the type of mathematical challenge fit for a logistics consulting firm, or perhaps a supercomputer, given the looming deadline – just a matter of weeks – to determine the fate of the semester.

Cornell turned to its School of Operations Research and Information Engineering, where faculty and students live and breathe mathematical modeling, optimization and analysis for data-driven decision-making.

With the clock ticking, Cornell needed an exceptional and dependable plan to keep its campus and community safe.

What does 6 feet apart even mean?

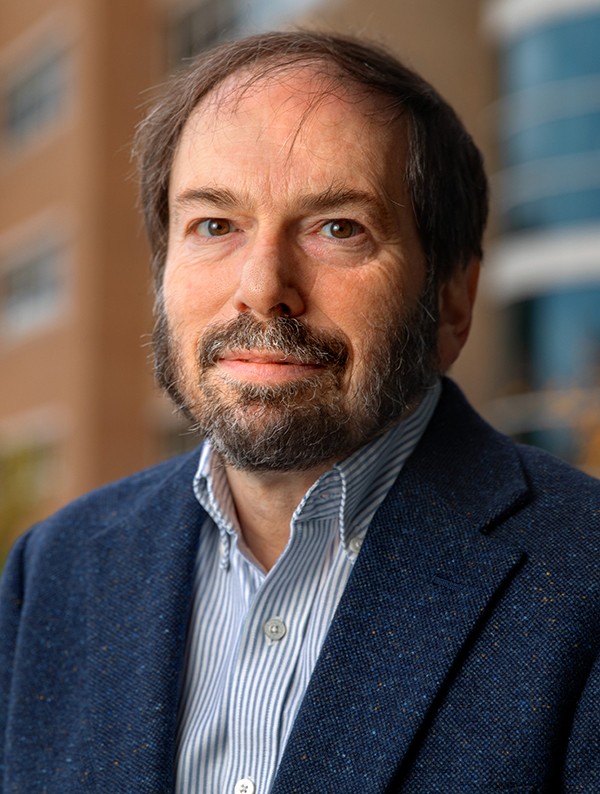

To identify options for the fall semester, Cornell assembled the Committee on Teaching Reactivation Options, comprising faculty, students and staff, including David Shmoys, the Laibe/Acheson Professor of Business Management and Leadership Studies.

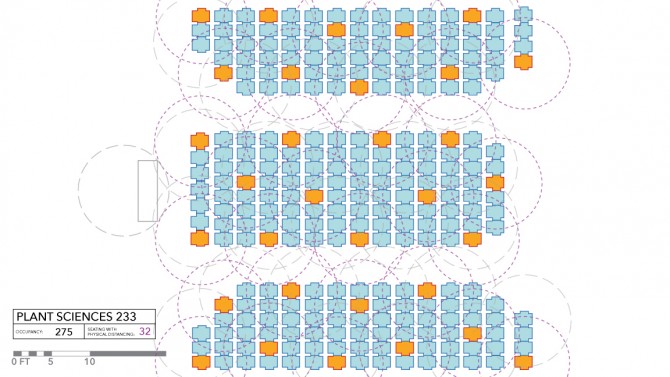

The committee knew Cornell could host in-person classes only if students in lectures could sit at least 6 feet apart.

Determining how much classroom space the university had was a capacity-planning exercise similar to what Shmoys would normally assign in one of his undergraduate courses. But with so little known about coronavirus and the coming semester, it was far from a typical exercise.

“How many instructors would want to hold classes in person and what capacity would we have in order to do that? Which classrooms have fixed seating and which have movable seating?” says Shmoys. “There were all kinds of issues coming into play and we were trying to understand what the limits really looked like.”

Another challenge was interpreting what 6 feet of social distancing really means.

“Is it from the center of the seat to the center of the other seat? Is it from the edge of the seat to the edge of the seat?” says Shmoys. “That one little change of phrase could make a 30% difference in terms of the number of seats that you can fit into an existing space.”

The Tompkins County Health Department clarified that social distancing means measuring from the center of one seat to the edge of the next.

Using an Excel spreadsheet, Shmoys began constructing a simple model with the help of then-undergraduate Brian Liu ’20, who assisted with data analysis and preparatory estimates. They determined that classrooms would hold roughly eight to 10 times fewer students than before the pandemic. That gave the university the answer it needed: Yes, an in-person semester did appear feasible – but only if course times and locations could be assigned appropriately.

By mid-June, the university had made its decision: The fall 2020 semester would be in-person, including online and hybrid approaches. Now, Cornell just needed a schedule.

Building a parallel university in six weeks

Lisa Nishii, vice provost for undergraduate education, turned to Shmoys. “I hope you weren’t planning on doing anything this summer,” she remembers quipping before asking Shmoys to co-lead the university’s Course Roster and Scheduling Team.

“It felt like we were building a parallel university in six weeks,” Nishii says. “All our normal institutionalized practices, the systems, the workflows, all of that totally shattered and we had to start from scratch.”

Co-leading the scheduling team was University Registrar Rhonda Kitch, who says being faced with building the entire university’s fall 2020 schedule was a daunting task.

“We knew developing the processes and tools needed to successfully build the roster and ultimately hold enrollment in the fall, or pre-enrollment for the spring, required optimization skillsets beyond the capacities within the Office of the University Registrar,” says Kitch.

Shmoys assembled an all-star team of his colleagues to contribute to the design and implementation of the schedule. The team included Oktay Gunluk, professor of practice and former manager of the Mathematical Optimization and Algorithms Group at IBM Research; David Williamson, a professor of operations and information engineering who specializes in optimization problems and scheduling; and Brenda Dietrich, the Geoffrion Family Professor of Practice and former vice president of IBM Research with decades of experience in applied optimization projects.

The group had just a matter of weeks to build, from the ground up, a schedule that would keep students safe.

Armed with blueprints for 484 classrooms and spaces large enough to accommodate more than 10 students, the group divided the problem into two challenges: determine the times of the classes, and assign the classes to classrooms.

“We went multiple directions simultaneously, so that there were different groups that worked on different approaches,” Shmoys says. “There were many different ways to decompose the problem into smaller problems and we explored some of the most promising ones in parallel because we knew we had a hard deadline and the goal was to be sure that we had something that we could hand to the registrar.”

In a normal practitioner setting, the scheduling challenge would be solved with a draft solution that would then go back to the client for review. Perhaps three or more iterations of the solution would be presented before the kinks would be worked out. But the scheduling team didn’t have that luxury.

“We had one shot and that was it,” says Shmoys. “We had to get it right.”

‘The project spiraled into being a 24/7 process’

While the Office of the University Architect and one of the faculty groups began reviewing classroom blueprints to determine each room’s new capacity, another group began building a schedule.

But how can a course be scheduled without knowing if a properly sized room will be available to host it? As a preliminary solution, the group categorized classrooms using a formula to determine how many students they thought each could hold – 16-20, 21-25 and 26-30, for example – hoping they had accurate enough estimates until better data was developed.

“The main approach we took was to model this using mixed integer programming,” says Gunluk, referring to a type of model in which some decision variables are not discrete. “And even in that case, you can build different kinds of integer programming models to deal with the same problem.”

Gunluk asked one of his Ph.D. students, Connor Lawless, if he had a couple extra hours to donate to the effort.

“I thought, ‘Sure, maybe I’ll read in some data, create a quick graph and get to learn more about scheduling problems,’” Lawless says. “Well, the model we were working on ended up being the winning one, and from that point onward, the project spiraled into being a 24/7 process for a month.”

There were many considerations: different options for class lengths, different combinations of days they could be scheduled on, and the need to schedule fewer classes at the same time in the same building to avoid crowding hallways.

But the main challenge was that Cornell had perfected its schedule in an iterative manner over the course of years, with many underlying assumptions baked into the schedule. For instance, almost every junior who takes ORIE 3300 is also taking ORIE 3500, so the registrar learned not to schedule those classes together. But over time that reasoning was lost as the schedule carried over from one semester to the next.

“There are all these idiosyncratic elements that go into making a schedule that most people, departments included, forget about until they look at a final schedule,” says Lawless. “We would assign something like a math class in Schwartz Auditorium … . But then you’d get waves of complaints arguing that everything from the location to the color or length of a blackboard was all wrong.”

Shmoys assigned Anders Wikum ’21 to find a way to extract as much of that historical judgement as possible from previous semesters.

Wikum’s job was to “let the data speak” by finding annual trends in which students concurrently enrolled in two courses.

A way to automate the process

As one group of engineers began homing in on a rough schedule, another was trying to develop a precise list of how many students each classroom could hold. It was a tedious process going through each room, one by one, examining the dimensions of the walls and calculating how many desks could fit while meeting health guidelines.

“We had been working with the registrar and Professor Shmoys through the first 100 or so spaces to ensure we were maximizing the number of seats while strictly adhering to health department spacing guidelines, required exit pathways, adequate ventilation and sight lines for AV,” says Margaret Carney ’81, university architect. “We needed a way to automate the process.”

Shmoys thought it was an interesting problem he could introduce to his Engineering Applications of Operations Research (ENGRI 1101) course. So he assigned undergraduate student Qihan ‘Jody’ Zhu ’22 to build a class exercise around room capacity, with operations research doctoral student Sander Aarts.

“It was basically just a maximum independent set at the core of the problem,” Zhu says. “If we could also figure out how to automatically recognize seats when given a floor plan, then one thing that we thought we could do better than the architect’s office was to speed up the process.”

Zhu coded a software program that could import classroom blueprints, read the floor plans and use computer vision to help identify where seats could be placed.

“Jody came back after one week,” Henry Robbins ’22 recalled. “She found an automated way to identify every seat in a room. This allowed rooms to pack an additional two to three seats compared to the architect’s model. It was pretty incredible to see the tool be produced so quickly.”

Shmoys, impressed with what his students had created, approached Carney with the software and asked if she was interested in using it.

“When Professor Shmoys offered the assistance of his students and the software program they had invented, I thought he was joking,” says Carney. “Luckily, it was no joke.”

In the end, the software helped identify more than 400 additional seats.

“We just kept working on it and eventually got the results the university needed,” Zhu says.

‘Are we going to have a schedule?’

With proposed course times and capacity determined, and with just days to spare, the groups could now merge their efforts into an initial schedule.

As knowledge of the coronavirus evolved, so did the schedule. When health officials recommended placing 20 minutes between classes instead of 15, the group had to adjust their model. Then, officials recommended every classroom be sanitized once in the middle of the day, in addition to a deep cleaning overnight. Once again, the model was fine-tuned.

“This modeling is partially an art; it’s not just math,” says Gunluk. “It is important to pick a model that can gracefully handle new information and constraints that come up later.”

With an initial schedule complete, hundreds of requests for changes began pouring in from the departments. Accommodating each request could mean the difference between students getting an in-person lecture and having to go virtual.

Using Lawless’ model, the group processed more than 250 requests, figuring out how to rearrange classes and building it into their model.

“Someone would communicate changes back to the departments. … Their response was usually ‘That doesn’t work either,’” Robbins says. “We processed these changes nonstop, every day for about a week.”

It was all coming together, but in the last days of developing Cornell’s fall 2020 schedule, everything still felt uncertain to the team.

“David would come to our daily meetings and introduce another big hurdle,” Robbins says, “and we’d question, ‘Are we going to have a schedule? Are we not? Will we even have a semester?’”

Nishii was also feeling the pressure. “I called the provost not that long before the start of the fall semester and I said, ‘I don’t know if we can do it. I don’t know if we have enough hours times humans to pull this off.’”

‘These are incredible students’

The team serviced requests and repeatedly updated the model, leading to a final effort to merge scheduling data with the registrar’s data.

A systematic data integrity check weeded out any undetected errors in the schedule. It was a four-day effort for Shmoys and his team, but finally, the weary group of faculty, students and staff had a completed schedule.

“The work of the past months has been intense,” says Kitch, who commended all who collaborated across campus to build the fall schedule. “These individuals have spent hours meeting and collaborating days, nights and weekends to meet goals and milestones. I’ve joked I spent more time in meetings with David than with my own family.”

But even with the schedule finalized, the job wasn’t complete. As the semester got underway, issues prompted the group to swing back into action.

“Because many of the rooms that were being used were brand-new to a class, you can have instances where an A/V configuration is almost unusable for a professor’s teaching style, or you have a discussion section for conversational Spanish in a lecture hall that turns out to be way too large,” Lawless says. “So we handled those as they came in.”

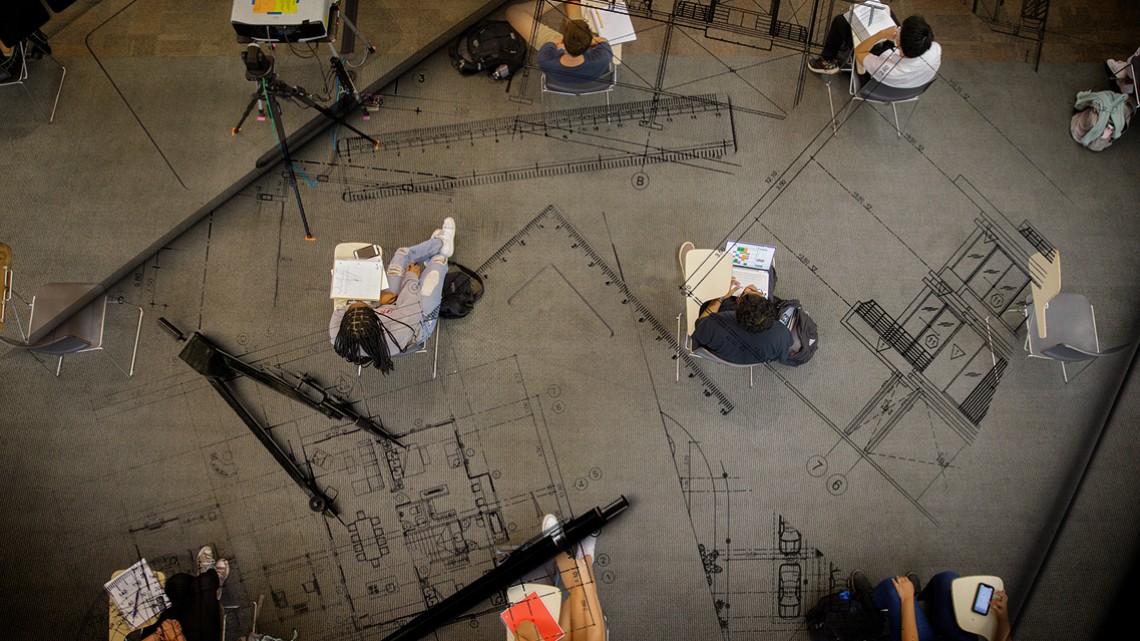

As the semester progressed, it became clear that the schedule was working. And after students went home for winter break, the university declared fall 2020 a success. In a message emailed to the Cornell community, Nishii said there was no evidence that COVID-19 had spread in a classroom setting. And despite a drastic reduction in classroom space, about 60% of students received some form of in-person instruction.

“We were very concerned that first-year students would get the least amount of face-to-face time because they tend to be in larger intro classes, which are more likely to be online because we don’t have the space,” says Nishii, “but as it turns out, they ended up faring quite well.”

Without Shmoys and the other faculty members from the School of Operations Research and Information Engineering, there may not have been an in-person fall semester, according to Nishii. She adds that Shmoys’ students are especially deserving of recognition.

“They’re brilliant,” says Nishii. “I hope they understand just how much they’re contributing to the functioning of the university. We couldn’t have opened without a course roster.”

“These are incredible students,” adds Shmoys. “To see them come together, commit and work incredibly hard – there were all-nighters that were done along the way to get things where they needed to be. They did it unflinchingly and they delivered.”

This article is adapted from “The unsung engineering behind Cornell’s fall 2020 schedule” by Syl Kacapyr, public relations and content manager for the College of Engineering.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe