‘Visions of Dante:’ seeing the Italian poet with new eyes

By Susan Kelley

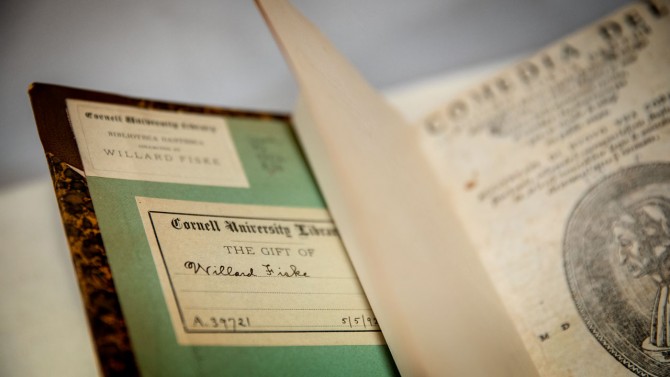

In 1892, as Willard Fiske, Cornell’s first librarian, was restoring a spacious villa in the hills overlooking Florence, Italy, he bought a small book. It was more than 350 years old with a “sad” binding. He’d later confess that he bought it only because he thought it was unusual – and inexpensive.

The book was a 1536 copy of the “Divine Comedy” by the medieval Italian poet Dante Alighieri.

Fiske sent the book to Cornell, downplaying its value in a postcard to interim Cornell Librarian William Harris. “No special value attached to the edition so far as I know,” he wrote. “Should the Library already possess a copy, please forward this to the library at Dryden.”

That little book was the first of an avalanche of material that now makes up the largest Dante collection in North America – the Fiske Dante Collection, at Cornell University Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (RMC).

The collection forms the foundation of the “Visions of Dante” exhibition at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. Marking the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, the exhibition of approximately 100 works in various media explores the visual nature of the “Divine Comedy,” which has inspired scholars and artists alike, from medieval times through today.

“A whole group of people – curators but also exhibition coordinators, registrars, conservators, photographers, video technicians and web designers – a joined forces to create one of the largest and most comprehensive exhibitions about Dante in 2021,” says exhibition co-curator Laurent Ferri, curator of pre-1800 collections in RMC.

“Visions of Dante” not only puts on display a large portion of the Fiske Collection for the first time. It also brings together works lent by notable institutions like the Morgan Library & Museum and 20th century and contemporary artists from William Blake to Salvador Dalí, Robert Rauschenberg and Kara Walker.

Each piece presents a different take on the “Divine Comedy,” in which Dante the narrator finds himself in an allegorical situation that every human can relate to: lost, alone and fearful in a dark wood.

With Virgil and his beloved Beatrice as guides, he travels to Hell, Purgatory and Paradise – described in the poem’s three parts “Inferno,” “Purgatorio” and “Paradiso.” Despite suffering and hardship – or maybe because of them – he emerges to reunite with God.

“This exhibition reasserts the continued vibrancy of the ‘Divine Comedy’ as a work of art, a work of literature, and shows the many ways in which visual artists have made their own personal interpretations and translations of that original text,” says co-curator Andrew C. Weislogel, the Johnson’s Seymour R. Askin, Jr. ’47 Curator of Earlier European and American Art.

The exhibition includes outreach programs to help learners of all kinds appreciate its works. Faculty members are encouraged to bring their classes to the exhibition. An Oct. 16 symposium will bring together scholars who will discuss the ongoing impact of Dante as a visual poet. And through the Central New York Humanities Corridor collaboration with the University of Rochester, college students from the region are encouraged to attend.

'Visions of Dante': Seeing the Italian poet with new eyes

Staff at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art install “Purgatorio” by Sandow Birk. The painting recasts Purgatory in urban America, with freeway ramps and a version of the “Hollywood” sign.

Advancing scholarship

Items in the Fiske Collection aren’t just old and rare; they’re interesting.

In 2019, Natale Vacalebre, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, came to the Fiske Collection to look at a unique book – and try to crack its unsolved mystery.

The 1472 copy of the first printed edition of the “Divine Comedy” has a remarkable feature. In its margins, someone wrote out a full transcription of a 14th-century commentary on the poem. Even more compelling were drawings in the margins, including diagrams of the levels of Hell, Purgatory and Paradise.

But no one knew who had written the commentary – or who had transcribed it and the drawings in the margins of the book.

Vacalebre wasn’t able to determine whose handwriting appeared in the margins. But he did discover what they had transcribed: a long-lost commentary by Neapolitan scholar Guglielmo Maramauro. Until then, researchers knew only of his commentary on “Inferno.”

“Cornell not only has a copy of the 1472 edition, but it has the most interesting copy of this book in the world,” Ferri says. “You may have copies in a better condition. But we find it much more interesting to have a book with a life, a book that proves that people were reading the ‘Divine Comedy,’ thinking about it, reflecting on the ideas, annotating it.”

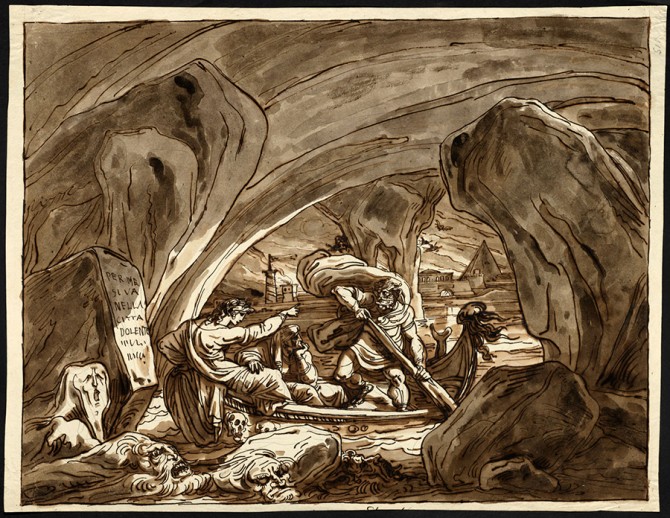

Ferri himself made an important discovery while thumbing through one of Fiske’s large-format scrapbooks. In fall 2020, Ferri discovered a previously unknown pen and ink drawing from around 1805 by Felice Giani, an in-demand artist of the time. “Virgil and Dante in the Bark of Charon” shows Virgil pointing out what is to come as Dante reclines pensively and Charon, Hades’ boatman, rows them toward Hell across the river Acheron.

One of the strangest features of the drawing – the howling, melting faces in the waves on the river – is something you’d expect from Salvador Dalí, not an artist who lived 150 years before him. “Here in a Neoclassical drawing, you have elements that are found in very different contexts with very different meanings,” Ferri says.

Frank Schroeder’s “Inferno,” a 2018 acrylic collage on canvas, includes the circles of Hell, suffering souls and references to works like Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica.”

Artistic interpretations

The exhibition also shows the many ways in which visual artists from diverse backgrounds have been inspired by Dante’s poem.

Frank Schroeder’s paintings generally draw on urban art, his French and Western African heritage, and his personal experience with the legacy of French colonial history and civil wars in Côte d’Ivoire. In his rendition of “Inferno,” Schroeder quotes from Henri Matisse’s “Dance,” Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica,” and Jean-Michel Basquiat – but that’s not all, Ferri says. “In one painting, we have this blend of pop art, hip hop, graffiti and classical references – including a tragedy mask from Hadrian’s Roman Villa in Tivoli – all going back to Dante, with these thrilling circles of Hell,” Ferri says.

Schroeder calls the painting “a sacred song of redemption,” Weislogel notes. “He’s offering the possibility that the struggles one encounters in Hell and Purgatory can be a crucible that remake you as a person,” he says.

Kara Walker demonstrates the same point, as an artist who chronicles the brutality the Black body has experienced in America via the Atlantic slave trade and the plantation economy. Her mixed-media work “Dante (Free from the Burden of Gender or Race)” debuted in a September 2017 exhibition, a month after a violent white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the preservation of Confederate statues. “It’s her exploration of placing the Black female body into the context of Dante’s ‘Inferno’ – the purifying effects of hardship and the sheer struggle every day of being a Black female person in our society,” Weislogel says.

And Yasumasa Morimura, a Japanese artist who remakes famous works of art by inserting himself in them, reimagined himself in his work “Self Portrait (Poppy)” as Beatrice in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting “Beata Beatrix.” “Morimura really complicates the concepts of masculine and feminine beauty and sexual orientation by taking on the storied relationship between Dante and Beatrice, which is the foundational principle of the ‘Divine Comedy,’” Weislogel says. “Morimura is helping us examine that in a new way, which I think is really appropriate for this exhibition and the present moment.”

Added Ferri: “These artists are living proof that even if you’re from a different tradition – maybe Italian is not your language, maybe you’re not interested in the Middle Ages, or maybe you don’t believe in God – Dante is still for you.”

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe