The earable performs as well as camera-based face tracking technology but uses less power and offers more privacy.

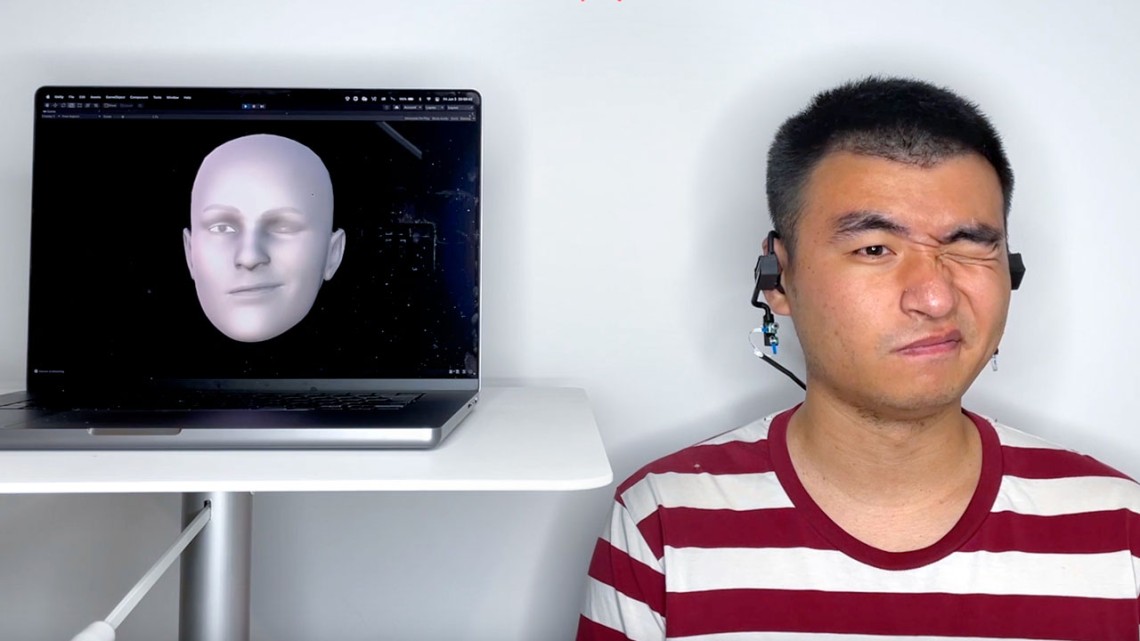

‘Earable’ uses sonar to reconstruct facial expressions

By Patricia Waldron

Cornell researchers have developed a wearable earphone device – or “earable” – that bounces sound off the cheeks and transforms the echoes into an avatar of a person’s entire moving face.

A team led by Cheng Zhang, assistant professor of information science, and François Guimbretière, professor of information science, both in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, designed the system, named EarIO. It transmits facial movements to a smartphone in real time and is compatible with commercially available headsets for hands-free, cordless video conferencing.

Devices that track facial movements using a camera are “large, heavy and energy-hungry, which is a big issue for wearables,” said Zhang, principal investigator of the Smart Computer Interfaces for Future Interactions (SciFi) Lab. “Also importantly, they capture a lot of private information.”

Facial tracking through acoustic technology can offer better privacy, affordability, comfort and battery life, he said.

The team described their earable in “EarIO: A Low-power Acoustic Sensing Earable for Continuously Tracking Detailed Facial Movements,” published this month in the Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies.

The EarIO works like a ship sending out pulses of sonar. A speaker on each side of the earphone sends acoustic signals to the sides of the face and a microphone picks up the echoes. As wearers talk, smile or raise their eyebrows, the skin moves and stretches, changing the echo profiles. A deep learning algorithm developed by the researchers uses artificial intelligence to continually process the data and translate the shifting echoes into complete facial expressions.

“Through the power of AI, the algorithm finds complex connections between muscle movement and facial expressions that human eyes cannot identify,” said co-author Ke Li, a doctoral student in the field of information science. “We can use that to infer complex information that is harder to capture – the whole front of the face.”

Previous efforts by the Zhang lab to track facial movements using earphones with a camera recreated the entire face based on cheek movements as seen from the ear.

By collecting sound instead of data-heavy images, the earable can communicate with a smartphone through a wireless Bluetooth connection, keeping the user’s information private. With images, the device would need to connect to a Wi-Fi network and send data back and forth to the cloud, potentially making it vulnerable to hackers.

“People may not realize how smart wearables are – what that information says about you, and what companies can do with that information,” Guimbretière said. With images of the face, someone could also infer emotions and actions. “The goal of this project is to be sure that all the information, which is very valuable to your privacy, is always under your control and computed locally.”

Using acoustic signals also takes less energy than recording images, and the EarIO uses 1/25 of the energy of another camera-based system the Zhang lab developed previously. Currently, the earable lasts about three hours on a wireless earphone battery, but future research will focus on extending the use time.

The researchers tested the device on 16 participants and used a smartphone camera to verify the accuracy of its face-mimicking performance. Initial experiments show that it works while users are sitting and walking around, and that wind, road noise and background discussions don’t interfere with its acoustic signaling.

In future versions, the researchers hope to improve the earable’s ability to tune out nearby noises and other disruptions.

“The acoustic sensing method that we use is very sensitive,” said co-author Ruidong Zhang, a doctoral student in the field of information science. “It’s good, because it’s able to track very subtle movements, but it’s also bad because when something changes in the environment, or when your head moves slightly, we also capture that.”

One limitation of the technology is that before the first use, the EarIO must collect 32 minutes of facial data to train the algorithm. “Eventually we hope to make this device plug and play,” Zhang said.

Cornell Bowers CIS provided funding for the research.

Patricia Waldron is a writer for the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe