New technique puts rendered fabric in the best light

By Patricia Waldron

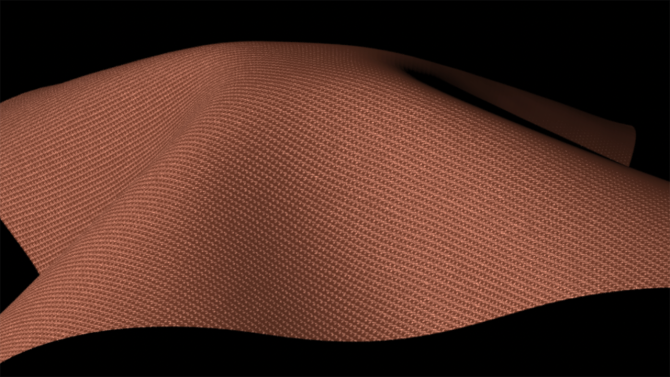

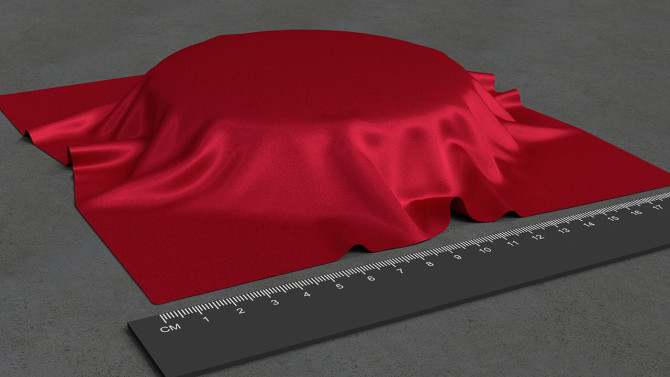

The sheen of satin, the subtle glints of twill, the translucence of sheer silk: Fabric has long been difficult to render digitally because of the myriad ways different yarns can be woven or knitted together.

Now, Cornell researchers, in partnership with the technology company NVIDIA, have developed a method for creating digital images of cloth that more accurately captures the texture of textiles.

The team’s new study, presented Dec. 16 at the Association for Computing Machinery’s SIGGRAPH Asia 2025 meeting in Hong Kong, models how light interacts with yarns – both as it passes through and reflects off the fabric. The advance is the latest to emerge from the lab of Steve Marschner, professor of computer science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, who has worked on this problem for more than two decades.

Film industry people always complain about how difficult it is to render fabric, said Marschner, who was on a team that received a 2004 Technical Achievement Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for work on rendering translucent materials. “It’s just hard to get it to look right. It always looks fake.”

At its smallest level, fabric is composed of tiny fibers twisted together to make a strand called a ply. Multiple plies are twisted together to form yarn, which is then woven or knitted to create fabric. Unlike materials such as metal or skin, which have a solid, continuous surface, fabric is “just a bunch of fibers floating in space that happen to be held together by friction,” Marschner said.

The shape of the fibers also varies depending on the material. Cut through a fiber of wool and the end will look almost oval; cotton fibers have a kidney shape and silk looks like three- or four-sided polygons.

“It makes the structure so interesting but so difficult to model,” said Yunchen Yu, a doctoral student in the field of computer science and the study’s first author. “I think there’s never going to be one fabric model that everyone uses.”

Marschner first began researching methods for rendering fabric when he started as an assistant professor at Cornell in 2002. His first doctoral student, Piti Irawan, Ph.D. ‘08, developed a simple method that modeled how light reflects differently off fibers at different points on the cloth’s surface.

After realizing that the underlying fiber structure dictates a fabric’s appearance, Marschner began modeling fabric in a more comprehensive way. Along with Shuang Zhao, Ph.D. ’14, and Kavita Bala, provost and professor of computer science, he used a microCT scanner to image at the scale of the woven fibers. This level of detail allowed them to render fabric more accurately, but scanning was expensive and time-consuming.

Eventually, they made the process more efficient, so they didn’t need to scan each fabric they rendered. This work turned into a side project with Brooks Hagan, a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, that enabled interior designers to visualize textiles for the production of custom fabrics.

Meanwhile, Marschner’s lab had been working with Doug James, then an associate professor of computer science at Cornell, now at Stanford, making physical simulations of how yarns and fibers are arranged in woven and knitted materials, and how that impacts their appearance. The team made advances in rendering patterns in knitted cloth, and predicting how a knit pattern will ultimately look when executed with yarn.

In the new study with Andrea Weidlich, a principal researcher at NVIDIA, Yu went further by considering how light interacts with cloth, both as a ray and a wave. She modeled light rays that bounce off the fibers – similar to Irawan’s initial model – and light waves that bend and diffract as they pass through gaps between fibers. This was the first fabric model to take wave optics into account, and built off her recent work rendering iridescent feathers.

At first, she tried to model the fabric’s appearance entirely using wave optics, but the simulation was too computationally intensive. Then, she discovered that using ray optics, which is about 1,000 times faster, works well for generating the average color of the fabric and look of the highlights. She could then save the slower wave-optics simulations to render the light shining through the fabric from behind, and for the subtle glints, sparkles and imperfections that make the images look especially realistic.

With this method, Yu must simulate how light interacts with each new type of fabric she renders. But, ultimately, she hopes to employ artificial intelligence to skip the simulation step, making the model faster and more flexible.

Marschner expects that incorporating generative AI techniques will be the key to more efficient fabric modeling for the gaming and animation industry. This will result in higher quality renderings, not just for high-budget animated films, but also for more widespread use, such as in video games.

“We have come a long way since 2002,” Marschner said. “It’s funny to look back at some of the things that we thought looked really good back then.”

Bruce Walter, a research associate at Cornell, also contributed to the research.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Patricia Waldron is a writer for the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe