Naked mole-rats share food with a chirp and a wave Cornell study of social rodents traces recruits' route to roots

By H. Roger Segelken

Worried parents with greedy kids may now have the ultimate role model: subterranean Africa's naked mole-rats that can't wait to share newly-discovered food sources with their kin.

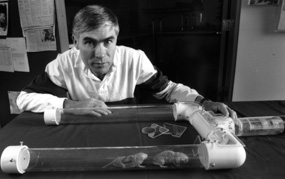

As reported in the November 1996 issue of Animal Behaviour (Vol. 51, pp. 957-69) by Paul W. Sherman of Cornell University and Timothy M. Judd of Colorado State University, the nearly hairless and sightless rodents would rather recruit family members to the site of food they found than eat the food themselves. The biologists watched and listened through transparent laboratory burrows as one mole-rat after another took an altruism test that many humans would fail.

In various sites in a plastic tunnel maze, the biologists had placed pea-sized bits of sweet potato. That simulated conditions in Africa, where the chisel-toothed rodents dig miles of burrows in search of the small bulbs and tubers that sustain them. Tuber patches in mole-rats' natural habitat are widely and irregularly dispersed, explained Sherman. Naked mole-rats (Heterocephalus glaber) must chew through lots of hardpan dirt to find a patch of tubers. But once they find a new source, there is usually plenty to go around.

How do mole-rat "scouts" recruit others to their newly discovered food source? That's what Sherman, a professor of animal behavior at Cornell, and Judd, a Cornell undergraduate at the time of the experiments and now a biology doctoral student in Colorado, wondered. And how do other mole rats, in colonies that average 75-80 closely-related kin, find their way through pitch-black tunnels to the newest food source?

As soon as a mole-rat scout located the biologists' stash of sweet potato bits, it would pick up one piece in its mouth and scurry directly back to the nest chamber, making a distinctive "chirp" call along the way. Once in the nest, the biologists observed, the scout would wave the food aloft in its mouth for all to smell.

"The scouts rarely ate that first sample of food, although they sometimes had to struggle to keep it away from other mole-rats," Sherman said. "Usually, the scout dropped the sample in the corner of the nest chamber without consuming it."

The chirp-and-wave recruitment maneuver set off mini-stampedes of mole-rat recruits, and the biologists were ready. They had constructed their plastic labyrinth with several alternative food sources -- in addition to the ones the scouts had discovered -- to learn how recruits find their way to the new food sources without the scouts to guide them.

More often than not, the recruits ignored the alternative food sources and followed routes to the roots their scouts had found. The recruits may be following the scouts' signature scents, which are left in the tunnels or they may be following "map directions" provided by the scouts. To test that hypothesis, the biologists switched the tunnel through which the scouts had traveled to the other side of the maze. They found that recruits followed the scouts' trails but not their directions. When tunnels through which scouts had traveled were replaced with clean tunnels, the recruits were confused.

Recruitment behaviors to share newly discovered food sources are well known in the animal kingdom, Sherman said, pointing to honey bees, ants and some bird and primate species. "Very different species have evolved similar communication signals to ensure survival, " he said. "In the case of the mole-rats and social insects, if the foragers don't share their knowledge, the rest of the colony may starve -- and fail to pass on their nearly identical genes. Food recruitment is a way for individuals to enhance what evolutionary biologists call 'inclusive fitness.' "

Apparently naked mole-rats do not "dance" to give directions behaviorally, as do honey bees, but lay down chemical trails, as do some ants and tent catepillars. However, the Cornell study did earn naked mole-rats one mark of distinction: Their newly identified recruitment chirp, issued by the food-bearing scouts on the way to the nest, brings to 18 the total number of different vocalizations. That gives naked mole-rats the largest vocal repertoire of any known rodent.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe