CU researchers use Mars enthusiasm to promote science, engineering to girls

By Blaine Friedlander

PASADENA, Calif. Women are from Mars, too. On that point, Cornell researchers Elaina McCartney and Zoe Learner, both working with the Mars rover science team, will not disagree.

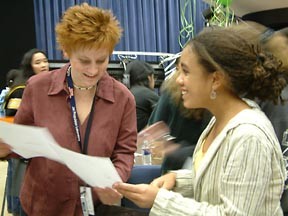

Before a crowd of budding female engineers and scientists, all in their preteen and early teenage years, at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the two women enlivened an evening symposium Feb. 26 on how to become the dreamers, the researchers and the builders of tomorrow.

The symposium, "Women Working on Mars," was part of JPL's Introduce a Girl to Engineering Day, an annual outreach event that encourages young women to consider a career in engineering or science.

Learner, a graduate student in space sciences, and McCartney, a space mission planner, are working with the panoramic camera team for the Mars rover mission. They were joined by JPL researchers Shante Wright, a thermal engineer, and Julie Townsend, an avionics engineer, in speaking of their positive experiences in space research.

Learner, the youngest member of the astronomical quartet, instantly beamed when asked how hard work as an undergraduate had paid off for her in the form of a distinctive graduate school adventure. "I've had a unique experience since I get to have Mars as my classroom," she said.

About 40 students from the Los Angeles area, dressed in their letter jackets and sweats and school-uniform skirts and penny loafers, attended the symposium, which was Webcast by NASA. The panelists took questions from the audience and from young women watching the symposium on television monitors in West Virginia, Canada and France.

When asked about her daily routine, McCartney explained that she has been living on Mars time during the mission and "losing" 39 Earth minutes a day (a Martian day, or sol, is 24 hours, 39 minutes and 35 seconds). The windows where she works are blocked out so she can't see the sun. After her shift, she is always surprised, she said: "Oh, it's night. Oh, it's day ..." Or "Oh, it's dawn," Townsend quipped.

All four panelists recommended an education heavy with mathematics and science classes, but Learner prescribed keeping the education broad. "Take a variety of classes all the way through college," she said.

After the Webcast, the students were split into age groups and given an opportunity for discussion. McCartney was peppered with science, and pseudo-science, questions by seventh-graders. How does life start on a planet? What can the rovers find? What would happen if a Martian creature attacked the rover?

One student at Learner's table pointed to a full-scale mock-up of a spacecraft in the JPL auditorium. "What's that?" she asked.

Learner's face lit up. "This is Voyager," she explained. "It was sent out to explore the universe before you were born."

Voyager. They had never heard of the two spacecraft, Voyager 1, which has been traveling through space for more than 26 years and is the most distant human-made object in the universe, and Voyager 2, which is close on its heels. Learner was on a roll. The Voyagers, she said, provided the first close-up images of Jupiter and Saturn, and Voyager 2 was the only spacecraft ever to fly by Uranus and Neptune. "If you look at the base [of the two Voyagers], you'll see a gold circle. It's a message from humans here on Earth. It's got a picture of a man and a woman on it. It's a record and it gives instructions on how to play the record. It has sounds of water running, birds chirping and kids saying 'hello' in different languages."

Savannah Greene, 13, of Pasadena, leaned closer to Learner as she asked, "Do you think there's life in the universe?"

Learner knew she had made a connection. She grinned at Greene and replied, "I have no doubt."

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe