Cornell astronomers jubilant as Cassini returns 61 spectacular images of Saturn's rings

By David Brand

PASADENA, Calif., June 30 -- Just hours after Cassini-Hugyens rocketed into orbit around Saturn at 7:36 PDT (10:36 EDT) June 30, the spacecraft sent back 61 images of the giant planet's rings that researchers acclaimed as astonishing and mind-boggling. "I'm surprised at how surprised I am at the beauty and clarity of the images," said Carolyn Porco, the imaging team's principal investigator, speaking at a press briefing at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) today (July 1).

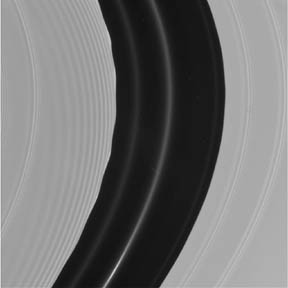

Said Porco, who is with the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., describing one picture of the Encke Gap, a small gap in Saturn's A ring, "I'm still not convinced it's real. It's so sharp."

Cornell astronomers Joseph Burns and Peter Thomas, two of her team members who are helping with the analysis of the images, which show the closest views ever obtained of Saturn's rings, said they were looking at "spectacular" structures never seen before.

The narrow angle camera on Cassini took the images soon after the main engine burn that put Cassini into orbit on Wednesday night. The spacecraft was hurtling at 15 kilometers per second (about 34,000 miles per hour), so only pieces of the rings were targeted. The images were taken by Cassini as it flew about 10 times closer to the rings than it will at any point during the mission, passing about 20,000 kilometers (12,427 miles) above Saturn's cloud tops.

"Some images, as Carolyn said, are textbook examples. But textbooks are just simulations, and we didn't actually know they were true," said Burns. "But after looking at 61 pictures, the structures around the rings are very surprising. We certainly didn't expect to see anything like that."

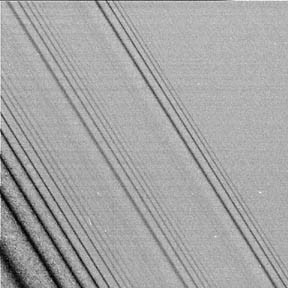

As one example, Burns cited periodic bands threading through the rings and "kinks" visible in the main ring. He also noted the clear interactions between some of Saturn's 31 known moons and the rings.

"Considering the lighting conditions and that the spacecraft camera was snapping these off with the shortest possible exposure, they came out very well," said Thomas.

Porco noted at the press briefing that one ring image showed structures resembling straw, that she said were mystifying researchers. "I literally don't have a clue," about what they are, she said.

Thomas said the straw, or mottled "whisps," were such a surprise "that they literally ground us to a halt." The mottling, he said, "was something we didn't even have a prediction for."

Said Porco, "The images are mind-boggling, just mind-boggling. I've been working on this mission for 14 years and I shouldn't be surprised, but it is remarkable how startling it is to see these images for the first time."

Some images show patterned density waves in the rings, resembling stripes of varying width. Another shows a ring's scalloped edge. "We do not see individual particles but a collection of particles, like a traffic jam on a highway," Porco said. "We see a bunch of particles together, then it clears up, then there's traffic again."

It had taken the spacecraft seven years to travel the 2.2 billion miles from Earth to Saturn, and so distant is the planet, the second largest in the solar system, that it took 84 minutes for signals to reach Earth confirming that the spacecraft had reached its target.

Cassini went into orbit (a process called SOI, or Saturn orbit insertion, by engineers) around the planet at 7:36 p.m. PDT (10:36 p.m. EDT), but it was 9:12:04 p.m. in Pasadena before the news crossed space to JPL .

The spacecraft is now in an orbit that will take it 116 days to make a single journey around Saturn. This orbit will gradually be reduced to 60 days.

Other Cornell researchers on the imaging team, besides Burns, the Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering, Theoretical and Applied Mechanics as well as professor of astronomy, and Thomas, a senior researcher in astronomy, are Joseph Veverka, professor and chair of the Department of Astronomy and astronomy professor Steve Squyres. The team will analyze about 300,000 images of Saturn and its environs over four years Also on the mission are Cornell astronomy professors Peter Gierasch and Philip Nicholson.

At 7:29 p.m. PST news reached JPL that Cassini had safely made the crossing of the ring plane. Minutes later, Cassini began executing a series of commands to enter orbit around the planet. The spacecraft then fired its main engine for a crucial 95 minutes to slow down and be captured in orbit around Saturn. If the burn had fallen much short (a 96 minute burn had been planned), or had failed to occur, the spacecraft would have flown by Saturn and then have been thrown by the giant planet out of the solar system. Said a mission controller, "God speed Cassini-Huygens. May we see you in orbit."

Cassini carries 12 instruments that will study the planet, rings and moons in extensive detail. Riding aboard Cassini is a second spacecraft, the Huygens probe, built by the European Space Agency. It carries half a dozen instruments that will study Titan, Saturn's largest moon. Titan is the only moon in the solar system to have a dense atmosphere and resembles the early Earth in deep freeze.

Eighty-five minutes before the engine burn, Cassini rotated to point its main antenna dish forward. The Italian-built antenna, 4 meters (13 feet) in diameter, offered shielding against dust particles the spacecraft might hit as it crossed a gap in the rings. Cassini passed twice through a known gap between the F and G rings, first while ascending shortly before the burn, then while descending shortly after the burn.

The engine burn slowed the spacecraft by 626 meters per second (1,400 miles per hour). Five science instruments were on during the burn, and others were used shortly after the engine cut off. The magnetometer measured the strength and direction of the magnetic field to understand the physics of Saturn's magnetic dynamics. Another instrument provided a record of the dust hits as the spacecraft flew through the ring plane. The remote sensing instruments analyzed the rings' composition, temperature and structure.

The final moment of anxiety ended at 9:30 p.m. when the spacecraft made its "call home," telling mission control that it had pointed its high gain antenna towards Earth, ready to relay the first close-up pictures of Saturn's rings.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe