Lab of Ornithology launches new search for elusive ivory-billed woodpecker's roost

By Krishna Ramanujan

BRINKLEY, Ark. - Main Street of Brinkley, Ark., is riddled with reminders that the ivory-billed woodpecker, believed to be extinct for decades, was rediscovered last year just a few miles from the edge of town in the Bayou DeView, a fingerlike tributary that feeds the Cache River system. The small town (pop. 4,000) now boasts the Ivory-billed Inn, an ivory-billed burger and a $25 woodpecker haircut - at Penny's Family Hair Care - a red, white and black pompadour.

The town also played host to the media Dec. 12 at a hunting lodge outside of Brinkley for a press conference to announce that a new search for the ivory-billed woodpecker is now in full swing. Presiding at the conference were officials from Cornell University's Lab of Ornithology, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Audubon Arkansas, The Nature Conservancy and the National Resource Conservation Service.

"Our big hope and goal is to find a roost hole or preferably a nest hole," said Lab of Ornithology Director John Fitzpatrick. "That's our holy grail."

Such a find would allow for repeat observations of an ivory-billed woodpecker, or possibly a pair. Researchers would map the bird's home range, observe feeding and nesting habits and better understand the woodpecker's behavior.

The information could feed ongoing efforts by The Nature Conservancy and other groups to protect the bird's habitat within the bottomland forests of the Big Woods of Arkansas. The Nature Conservancy recently purchased almost 20,000 additional acres near where the bird was first spotted. The long-term goal is to add another 200,000 acres to the Big Woods, which currently covers 550,000 acres mainly within the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge and the White River National Wildlife Refuge.

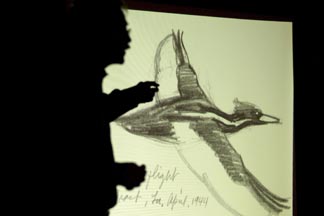

The ivory-billed woodpecker was believed to be extinct for 60 years due to loss of habitat until a kayaker, Gene Sparling, saw one in the Bayou DeView in February 2004. Two weeks later, birder and Cornell Lab of Ornithology editor Tim Gallagher and his close friend Bobby Harrison, a birder and director of the Art Program at Oakwood College in Huntsville, Ala., saw an ivory-bill fly in front of their canoe at close range in the same area. Then, on April 25, 2004, University of Arkansas Professor David Luneau finally captured the mystery bird on videotape.

In early June 2005, following an April 28 public announcement, a paper led by Fitzpatrick was published in Science magazine offering proof of the bird's rediscovery. Among other evidence, the paper referred to seven of the best-documented eyewitness sightings -- there are now a total of 18 credible sightings all within a few miles of each other -- and the carefully analyzed, though fuzzy, video of the bird.

A search from December 2004 through April 2005 also yielded recordings of the bird's characteristic "kent" calls from both the Cache River and White River areas. Recordings from the White River revealed distinctive double knocks on tree trunks, a signature of these woodpeckers. The audio came from Cornell's automated recording units (ARUs), digital recorders planted in trees. One recording suggests two birds double knocking in a call and response.

Still, skeptics remain. The ivory-bill closely resembles the smaller red, black and white pileated woodpecker common to the area. And blue jays are known to make sounds similar to the ivory-billed woodpecker's nasal toot.

However, Ron Rohrbaugh, director of the Lab of Ornithology's Ivory-billed Woodpecker Research Project, emphasized at the Brinkley event, "We think we have all the proof we need." He added that the focus now is to learn more about the bird's habits. "But there certainly would be nothing wrong with a nice eight-by-ten glossy to satisfy some of the critics."

Last year's search stopped in April, as summer brought heat, bugs, snakes, relative silence from the woodpecker itself and an impenetrable canopy that made searching for an already elusive bird close to impossible. This winter the odds are already against searchers given the Big Woods' massive size and the bird's large range and nomadic nature. Last year's search effort, for example, employed 36 volunteers who collectively spent tens of thousands of hours in the swamp surveying about 8 percent of the Big Woods total area.

The current effort, which began Nov. 1, includes 22 full-time staffers hired and trained by the Lab of Ornithology, including ornithologists and field biologists, team leaders and coordinators and field technicians. Also, the first 14 out of a total of 112 volunteers began working in the field Dec. 5. The volunteers, chosen from an applicant pool of 300, will arrive 14 at a time and work in two-week shifts over the course of the next six months until conditions again become untenable.

The new search will include more deployment of ARUs, time-lapse video systems, remote motion/heat-triggered still cameras, use of Global Positioning Systems and NASA satellite imagery to scout for the woodpecker's habitat.

This second search is being funded with private donations and some of the Lab of Ornithology's own membership support. Also, the federal government is providing acoustic technology equipment.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe