For Howard Evans, whole world is a classroom for a teacher, an anatomist and a raconteur

By Jeanne Griffith

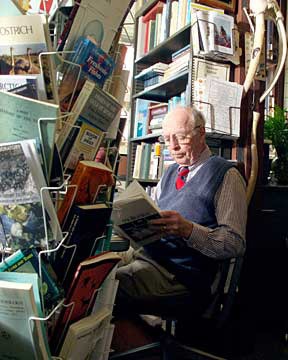

Howard Evans is going on 85, but beneath the veneer of age lurks a bright, adventurous boy who spent his early years looking under rocks and catching bugs and frogs in New York City's Central Park – and who could tell you the classification, preferred habitat, dietary predilections and mating behavior of the prize he held clutched in his hand.

That lively boy is now a Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine professor emeritus of anatomy who has taught thousands of veterinary students (including three former deans of the Vet College) since 1950 and led legions of alumni on some 30 Cornell Adult University (CAU) tours to the various ends of the Earth. He is a profound and thoroughgoing scholar who has never lost the sense of unreserved wonder of childhood and who has joyfully spent a lifetime reaching to wrap the entirety of life – animal and plant, ancient and extant – in one huge, inquisitive embrace.

For Evans, the whole world is a classroom, and class is always in session. During a CAU trip to Antarctica, for example, "he brought a starfish with about 50 arms to breakfast," laughs Roy Pollock, D.V.M. '78, Ph.D. '81. "We dissected an ice fish in the bar; right up on the bar! We found a dead penguin, so Howie dissected it right there on a big hunk of ice that had washed ashore. On a trip we took with him to the Galapagos Islands, we reassembled a sea lion from all the bits and pieces we found on the beach."

Evans is an anatomist by profession, but as far back as he can remember, he was interested in minerals, insects, fishes, reptiles and so forth. His interest in Cornell was sparked by an exterminator working in his apartment building. After Evans quizzed him closely about his methods, the exterminator told him he ought to go to Cornell, where they had a whole building devoted to insects. Evans enrolled in Cornell's New York State College of Agriculture in 1940 a few years later.

World War II cut short his student days on campus. As a ROTC student, Evans got called to active duty at the end of his sophomore year. Evans was awarded his Cornell B.S. degree in absentia in 1944 and, upon his discharge from the Army, returned to do his graduate work in zoology. In 1950, with a Ph.D. in comparative anatomy, Evans joined the faculty of the veterinary college. He has taught the anatomy of the horse, cow , dog and chicken, and when pet birds became popular, he added budgerigar anatomy to the curriculum.

His co-authored books "Anatomy of the Dog" (1964, now revised twice) and "Guide to the Dissection of the Dog" (1969) are both classics. The latter – a staple of veterinary curricula worldwide – recently went into its sixth edition. Evans has also written numerous book chapters or manuals on the anatomy of the budgerigar, ferret, reptiles and tropical fishes. Most recently, he and senior lecturer Braam Bezuidenhout finished a monograph on woodchuck anatomy.

While Evans' books have brought him name recognition, he looks back on the opportunity to teach veterinary students as the best part of his experience as an academic. He and his wife, Erica, have formed many enduring friendships with them and have even endowed a comparative anatomy award to help support their studies.

"He is a wonderful, wonderful teacher," declares Bezuidenhout. "Most veterinary anatomists can speak in depth about the anatomy of a certain structure in our domestic animals, but Howard can take it from there to birds, to fishes, to reptiles, amphibians . . . it doesn't matter what."

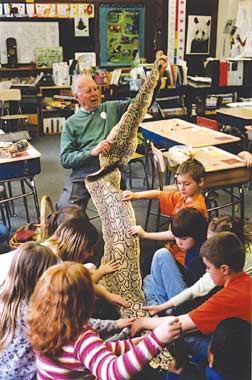

Evans still teaches a one-credit elective to veterinary students on natural history: a sweeping review of earth science, plant science, invertebrates, fishes, amphibians and reptiles, birds and mammals. He also carries a big basket of parts and pieces into area elementary schools twice a week to delight students with the ultimate show-and-tell. Another of Evans' many retirement activities is teaching fish and bird anatomy at the veterinary college at St. George's University on the island of Grenada.

"Howard has a huge international standing as a scientist," says Bezuidenhout. "I don't think there's a country in the world where veterinary science is taught that the name Howard Evans is not known. He retired a long time ago, but he still gets invited to veterinary colleges all over the place. Certainly he is known everywhere as an anatomist, but he is far more than that. He's most probably one of the last truly great naturalists."

Tales of the tale-teller

Cornell anatomist John Hermanson used to help Evans teach his course in fish and bird anatomy after Evans had officially retired. "I never knew what the guy was going to talk about," Hermanson laughs. "It would be the anecdotes that came to his mind, silly things. Did you know that the swim bladder of a toadfish is actually a sonic device? The males use it to communicate; it's how they attract mates." Evans made that fact memorable by telling his classes how the arrival of toadfish mating season had sent the U.S. Navy into high alert one year during World War II. To protect against attack, the navy had laid sonic mines in Chesapeake Bay, their triggers tuned to the frequency of German U-boat propellers. When the toadfish began calling to their mates, many mines went off, causing the Navy to launch a frantic hunt for submarines.

There's logic to the Evans style. After relating the story of the toadfish versus the U.S. Navy, for instance, he describes how the Navy funded the development of a library of fish sounds that has helped underwater exploration. So we have the toadfish to thank for that.

For Evans, personal experience usually comes with a story attached. There is the story of the shark that held onto his thumb, a perennial favorite among schoolchildren; he has the shark's head in his basket to prove it. Another favorite concerns the belly-up electric torpedo ray on the deck of a fishing trawler at Cornell's Shoals Marine Lab that shocked Evans twice before he realized what it was and that it was alive.

Excerpted from Cornell Veterinary Medicine magazine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe