Cornell engineering students break down science of water plant technology for Hondurans

By Anne Ju

CIUDAD ESPAÑA, Honduras --- Passers-by peering into the room where Cornell engineering students were presenting a skit for Honduran community leaders might have wondered what all the hugging was about.

Flocculation probably would not have come to mind. But sometimes, it takes a little acting and a few laughs to make complex concepts come alive -- the science behind water treatment, for instance.

With narration, the students acted out the process of flocculation, which is when aluminum sulfate is mixed with water, causing clumps of particles, called flocs, to form (hence the hugging). The flocs then settle out in a process called sedimentation, leaving clean water behind.

The students' audience was a handful of municipal leaders of Ciudad España, a mixed-income community built following Hurricane Mitch in 1998, which destroyed thousands of Honduran homes.

With its neat rows of identical houses, save for the red, green or tan rooftops, Ciudad España was one of several communities the Cornell students on the AguaClara Project Team visited during their two-week stay in Honduras, Jan. 4-20.

Accompanied by their leader, civil and environmental engineering senior lecturer Monroe Weber-Shirk, the students toured existing and future plant sites in the developing Central American country. During the fall semester, several of Weber-Shirk's students designed a treatment plant for the town of Támara, a 20-minute drive from Ciudad España.

"They're getting all the context that includes not only the engineering, but all the other pieces that go into making this a successful project," Weber-Shirk said.

During the trip, the 18 students witnessed all stages of the process by which their Honduran partner organization, Agua Para el Pueblo ("Water for the People"), introduces water treatment plants into towns and villages. The Ciudad España trip exemplified the earliest stages of building partnerships with communities.

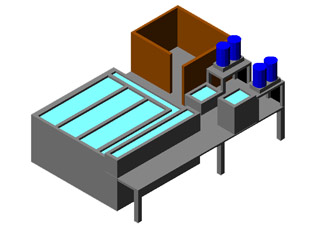

According to Agua Para el Pueblo social outreach coordinator Arnaldo Canales, Ciudad España has about 1,500 houses and about 7,200 inhabitants. The community also has a school and health center. But Ciudad España's water delivered through its existing system is treated only with chlorine. If built, a water treatment plant would be placed between the water source and distribution system. The water would be cleaned through the flocculation and sedimentation processes, and treated with chlorine afterward as a disinfecting agent before going to people's homes.

Before committing the resources, Agua Para el Pueblo must first decide whether a community is a good fit for a water plant. They encourage leaders to be committed to both raising funds for the project and getting people educated about potential community costs, including increased water tariffs.

These delicate balancing acts are why Weber-Shirk believes the students must be good ambassadors of the water plant projects, helping to pitch the idea to communities who might need them and helping to present the technology in understandable terms. (And who doesn't understand a hug?)

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe