Synchrotron unveils long-hidden N.C. Wyeth painting

By Anne Ju

Stubborn layers of paint had kept them hidden for several decades, but the bluish, purplish and reddish hues of a 1919 painting by 20th-century artist N.C. Wyeth have finally come to light, thanks to cutting-edge technologies developed at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS).

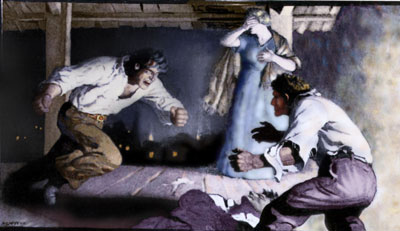

The careful visualization of a Wyeth magazine illustration depicting two men engaged in a brawl, only known previously in black and white, was publicly unveiled Aug. 19 at an American Chemical Society symposium by chemist and art conservation expert Jennifer L. Mass, M.S. '92, Ph.D. '95.

Mass, who collaborated on the Wyeth project with CHESS senior research associate Arthur Woll and art conservators Christina Bisulca, Noelle Ocon and Matt Cushman, described the powerful X-ray technology used to unveil the old painting, which Wyeth had painted over in about 1923 with his work "Family Portrait."

CHESS scientists, led by Woll, developed a technique called confocal X-ray fluorescence that harnesses the brilliant X-rays from the National Science Foundation-supported CHESS to deal specifically with the problem of painted-over paintings. They teamed with Mass, senior scientist at Delaware's Winterthur Museum and Country Estate, to study "Family Portrait" after it was discovered 12 years ago that a second work, the scene of a dramatic struggle from a 1919 Everybody's Magazine article titled "The Mildest Mannered Man," lay underneath it.

Their device focuses an X-ray beam onto a painting and collects the fluorescent X-rays given off by the chemicals in the various layers of paint. Each color of paint produces a unique fluorescence spectrum, like a chemical fingerprint, which can then be mapped to reconstruct the original color schemes in the hidden painting.

Confocal X-ray microscopy isn't new; it had been tried in Europe several years ago, but mostly on scientific specimens, said Sol Gruner, CHESS director and professor of physics.

"We built a setup specifically to look at large works of art," Gruner said.

The result of the CHESS project was the discovery of a painting once thought to be lost, two scientific papers describing the new confocal X-ray techniques -- and a few surprises.

For example, one might expect the burning furnace plume depicted in the rightmost part of the painting to glow a brilliant orange, Gruner said. As it turns out, Wyeth used a more subtle tone.

"The colors are quite pale, something that was surprising to us, and there were much more muted yellows and oranges, and more prevalent pinks and violets then we were expecting," Mass said.

The collaboration between art conservators and CHESS scientists is growing, Gruner said, with several other projects in the pipeline that involve specific works of art as well as old manuscripts.

Confocal X-ray fluorescence is a slow, arduous technique; scanning a portion of a painting the size of a quarter takes nine hours. A project at CHESS is also ongoing to look at ways to speed up this process, which would allow more art historians to access the technology, already applied in such disciplines as biology, archaeology and dendrochronology, said Ernie Fontes, CHESS assistant director.

"Confocal X-rays on paintings is still a very specialist niche," Fontes said.

Even so, Gruner expects that other synchrotron facilities will soon begin operating instruments for art conservation, given that the confocal technology is well known and accessible to synchrotron scientists.

"Our primary role in this, which is common for CHESS, is to lead by example," Gruner said.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe