Revolutionary high-agility satellite places second in national competition

By Shashwat Samudra

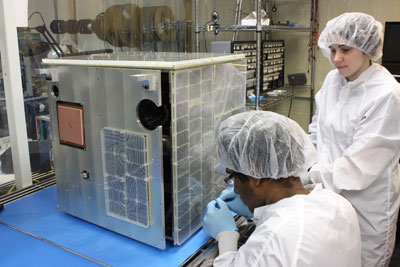

Violet, a new high-agility satellite designed by a group of Cornell engineering students, won second place in the sixth University Nanosatellite Program, a competition sponsored by the Air Force Research Laboratory.

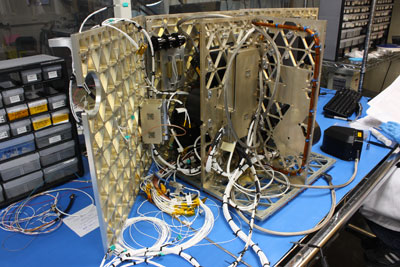

Named for the ultraviolet spectrometer it carries on board, Violet is revolutionary, say its creators, because of its efficient use of multiple control moment gyroscopes (CMGs). These are small rotors able to produce huge amounts of torque -- allowing the satellite "to more than double the agility of any spacecraft currently in orbit," said Violet's Integration and Test Lead Amanda Kuczun '12.

Most spacecraft use three or four CMGs, but eight are planned for Violet, as the team's main mission "is to demonstrate that small spacecraft with lots of CMGs can be very agile," said Kuczun, "and Violet has a lot of applications." These include future use in earth and space science, space exploration and commercial earth imaging for services such as Google Earth.

If nanosatellites such as Violet -- which weighs in at about 110 pounds, perhaps one-one-hundredth of the weight of many satellites -- see wide use, satellite technology would become more commercially accessible. Satellite launches "may become more frequent and, once again, drop in price, leading to a more robust space industry and one in which spaceflight is consumer driven," said mechanical and aerospace engineering associate professor Mason Peck, who is Violet's principal investigator and student team adviser.

Violet didn't place first in the competition, a distinction that would have set the satellite on a direct course toward a launch date. But the high interest it received from the aerospace industry and the Air Force means that it will likely launch "in late 2012, if all goes well … as [Violet's mission] is so relevant to the Air Force's research goals," Peck said. He is working with Air Force Research Lab managers to find Violet a launch opportunity.

In fact, aerospace companies provided a substantial part of Violet's funding and hardware. Locally based Ithaco Space Systems donated prototype CMGs; Northrop Grumman contributed a fiber-optic gyro, used to determine angular motion; and the Draper Laboratory provided Violet's spectrometer, which will aid the satellite in studying extrasolar planets. Other sponsors included alumni, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the College of Engineering.

What's in Violet's immediate future? The student team behind the satellite -- two years in the making -- is now working with the Air Force Research Laboratory to finalize a plan for Violet's launch. Minor improvements must be made to the flight software and assorted hardware components, while tests will be continuously run in mission control, located in the basement of Ward Lab. In short, according to Peck, with everything falling into place. "Violet's team will only have to rehearse its operational procedures" to prepare for next year's flight, he said.

Violet's success comes on the heels of Cornell's CUSat, a pair of twin satellites built by a previous generation of engineering students advised by Peck. In 2007, CUSat won the Nanosat-4 competition, and just recently, their satellite became a confirmed passenger aboard the Falcon 9, which will head into orbit in March 2012 about 20 kilometers (about 12 miles) lower than the International Space Station.

Shashwat Samudra '14 is a writer intern for the Cornell Chronicle.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe