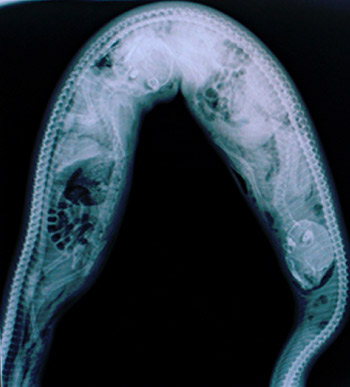

Study of man-eating snakes: Snakes are predators on, prey of, and competitors with primates

By Krishna Ramanujan

More than a quarter of the men in a modern Filipino hunter-gatherer group have been attacked by giant pythons, reports a study that also concludes that humans and snakes not only eat and are eaten by each other, but have long been competitors for the same prey.

Human aversion to snakes may be a result of a shared evolutionary history, researchers have often speculated, but since snakes swallow their prey whole, little fossil evidence remains to help define the relationship between snakes and primates.

The new study, published online Dec. 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides rare documentation of complex ecological and evolutionary relationships between primates -- including humans -- and snakes. It is one of the first to document 20th-century human hunter-gatherers as prey of, predators on and competitors with a wild predator. The research also uses natural history data to show that every major lineage of living primates is both eaten by and eats snakes.

"People have speculated for a long time that serpents have had a significant relationship with primates throughout their shared evolutionary history," said Cornell herpetologist Harry Greene, who conducted the study with Thomas Headland, an anthropologist at the SIL International in Dallas. "Our paper provides the strongest evidence yet for that relationship."

In the 1960s, Headland recorded ethnographic observations of the Agta Negritos, a modern hunter-gatherer group of small, dark-skinned people in the Philippines. An average adult male weighs about 90 pounds, small enough to be eaten by the huge reticulated pythons (Python reticulatus) that can grow to 28 feet.

His survey of 120 Agta revealed that 26 percent of the men (15 out of 58) and 1 out of 62 women, who spend much less time in the jungle, had been attacked by the pythons.

There were, for example, six fatal attacks between 1934 and 1973. In one such attack, a father entered his dwelling to find a python had killed two of his children and was swallowing one of them headfirst. The father killed the snake with his bolo knife and found his third child, a six-month-old daughter, who was unharmed.

"Imagine what it would be like to have to live in constant fear of a 25-foot snake coming out of the bushes and grabbing your leg," said Greene, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. But, the Agta also routinely ate the pythons as well as deer, wild pigs and monkeys, which the pythons also ate.

Headland's observations show that snakes actively attack and eat humans; before humans had iron knives and guns, it is likely that the Agta suffered many more fatalities to snakes, according to the paper.

The study also asserts that the threat of snake predation and competition with snakes over similar prey must have been a consistent pressure for hunter-gatherers. This was likely especially true for those small in stature, throughout human history, as well as for primates more generally, since dangerous snakes were present at the time of the group's origin some 70 million years ago.

The study was funded by the Louis S.B. Leakey Foundation and the Lichen Foundation.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe