Researchers discover what cancer cells need to travel

By Carly Hodes

Cancer cells must prepare for travel before invading new tissues, but new Cornell research has found a possible way to stop these cells from ever hitting the road.

Researchers have identified two key proteins that are needed to get cells moving and have uncovered a new pathway that treatments could block to immobilize mutant cells and keep cancer from spreading, said Richard Cerione, Goldwin Smith Professor of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology at Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine.

The study, co-authored by graduate student Lindsey Boroughs; Jared L. Johnson, Ph.D. '11; and Marc Antonyak, senior research associate, is published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry (286:37094-37107).

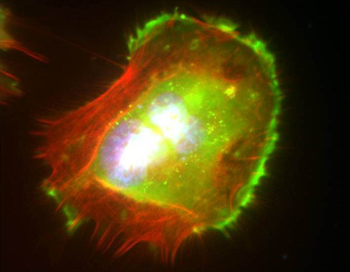

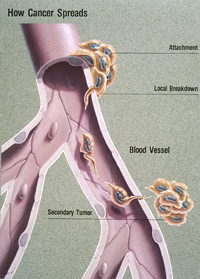

Most adult cells stay stationary, but the ability for some to move helps embryos develop, wounds heal and immune responses mobilize. When migrating cells go astray they can cause developmental disorders, ranging from cardiovascular disease to mental retardation. Metastasis (the spread of cancer from one part of the body to another) also relies on cell migration. How exactly cancer cells migrate and invade tissues continues to be a mystery. However, Cerione's lab uncovered a potentially important clue when it noticed that cancer cells gearing up to move would collect a protein called tissue transglutaminase (tTG) into clusters near the cell membrane.

"tTG is turning up in many aspects of human cancer research and seems to be contributing to the process that turns cells cancerous," said Cerione. "Lindsey and Marc discovered that cells must gather tTG into a specific place in their membrane before they can move. But tTG is usually inactive, and we've been trying to understand how a cell gets this protein to the exact right place so that it can be activated to stimulate cell migration."

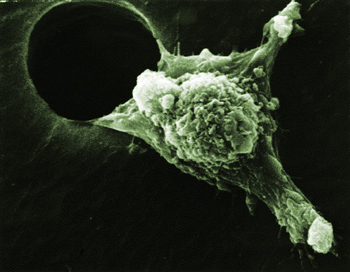

Observing breast cancer cells in culture, Cerione's lab found a missing link in our understanding of cell migration: Cancerous cells become hyperactive invasion vehicles by using tTG together with other proteins like wheels, poking them through the surface to form a "leading edge" that pulls the cell forward. But to get the wheels to the leading edge, it turns out they need another protein to roll them there -- a "chaperone" protein called heat-shock-protein-70 (Hsp70).

"We've known for years that Hsp70 acts as a chaperone to other proteins, ensuring that they assume the right structure and behave properly when a cell is under stress," said Cerione. "Heat shock proteins have also been implicated in cancer, although scientists have been trying to understand their exact role in cancer. Our research has uncovered a previously unknown role for these chaperones -- helping tTG get to the leading edge. tTG must be in this location for cancer to spread."

When cells become stressed, Hsp70 influences the behavior of their "client" proteins, ensuring they keep the right shape. Cells need chaperones like Hsp70 to ensure that various proteins work correctly and don't warp, but these same chaperones can help cancer cells spread by helping move tTG to the membrane surface. Using inhibitors that block the function of chaperones, Cerione and his team paralyzed Hsp70s and stopped breast cancer cells in culture from gathering tTG into a leading edge, effectively immobilizing them.

Exactly how Hsp70 gets tTG going remains unknown, but Cerione believes other proteins are involved.

"If we can better understand how Hsp70 influences tTG, we can figure out ways to modulate that interaction to immobilize cancer cells and keep them from becoming invasive," said Cerione. "We suspect Hsp70 is using a third kind of protein to move tTG, and that's what we're trying to figure out now. Finding the next link in this chain of events could have important consequences for preventing cancer migration and metastasis."

This work was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health.

Carly Hodes '10 is a communication specialist at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe