Buried ocean lends insight into Titan's dense, methane-rich atmosphere

By Anne Ju

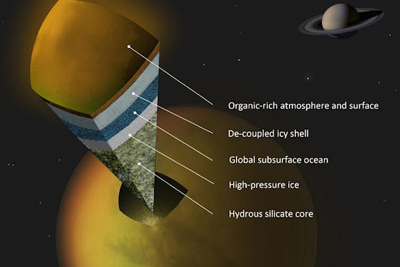

To better understand Saturn's moon Titan, scientists must study the methane in its atmosphere, the persistence of which was likely influenced by an ocean of water recently discovered 100 kilometers below the moon's surface, said Jonathan Lunine, Cornell's David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences.

Lunine worked with the radio science team of the NASA Cassini-Huygens mission, which reported in the journal Science June 28 that Saturn's most intriguing moon has a layer of liquid water underneath its icy shell -- and therefore a possible abode for life.

Using data from six Cassini flybys of Titan between 2006 and 2011, the scientists used precision radio tracking of the spacecraft to deduce the presence of the subsurface ocean from the moon's subtle squeezing and stretching as it orbited Saturn.

Titan is the only moon in our solar system with a dense atmosphere -- denser than Earth's. But most fascinating of all, Lunine said, is the large amount of methane, the simplest organic molecule, in its atmosphere. Picture lakes and rivers on Titan's surface not of water, but of bubbling methane and maybe even geysers like Old Faithful.

"All the things water does on Earth, methane does on Titan," Lunine said.

The presence of a liquid water layer within Titan can help scientists understand how methane is stored in the moon's interior and how it may come up to the surface.

"Everything that is unique about Titan derives from the presence of abundant methane, yet the methane in the atmosphere is unstable and will be destroyed on geologically short timescales," Lunine said.

The observations that led to the discovery of the ocean, Lunine added, are impressive feats of precision data analysis by the international Cassini research team led by Luciano Iess of Sapienza University in Rome.

"The team was able to measure incredibly small accelerations of the spacecraft due to the presence of Titan -- changes smaller than a millionth the acceleration due to gravity on the Earth. At those accelerations it would take a car roughly a month to go from 0 to 60 miles per hour," Lunine said.

Because every season on Titan is seven years long, Lunine added, researchers hope Cassini will continue to be supported by NASA through 2017 so they can observe Titan at the onset of southern winter and northern summer.

"Most of the methane lakes and seas are near the north pole ... we've never actually seen what happens when the sun shines directly on the methane lakes, so we are looking forward to that," Lunine said.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, and is managed by Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe